Laura Paskus

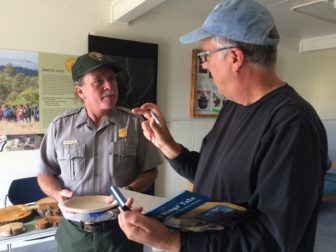

Talking with a fan, John Fleck signs a copy of his 2009 book, “The Tree Rings’ Tale: Understanding Our Changing Climate.” Photo by Laura Paskus.

Around the newsroom, John Fleck used to be called The Harbinger of Doom. When drought overtook New Mexico more than a decade ago, his stories regularly started running with headlines like: “New Mexico in its worst drought since 1880s,” “Conflicts rise as water dwindles,” and “San Juan water dries up for first time in 40 years.”

Initially covering science and the national laboratories, Fleck didn’t take over the water beat at the Albuquerque Journal until New Mexico was well into its most recent drought. “I was geared up to write about people running out of water,” he says today, sitting on his back porch and watching doves dip their beaks into a makeshift pond while black-chinned hummingbirds inspect the flowers. In 2013, when wells were running dry in the communities of Magdalena and Maxwell, he’d hit the road with a photographer, then bang out more depressing stories.

But the coverage didn’t feel quite right to him: “I began to realize there was this other story about people not running out of water,” he says.

Locally, for example, he points to a drop in Albuquerque’s water consumption. At the same time, as the city relied less on groundwater pumping and more on water from the Rio Grande, the aquifer started recovering.

“By the end, I was chafing under the constraint of what a newspaper story should be – 600, or maybe 750 words,” he says. Short, to-the-point, and focused on a crisis. In general, newspapers aren’t in the business of peddling stories about complicated issues and the subtle, nuanced solutions people devise.

Despite the nickname, Fleck just isn’t a gloomy guy. The grind of it all began to wear on him.

After three decades of writing short, punchy stories about crisis and conflict, he’s now thinking beyond day-to-day headlines. He’s also crafting deep arguments on how to solve the same problems he reported on before leaving the Journal last year. Today he’s an adjunct faculty member and writer-in-residence in the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program. His latest book, Water is for Fighting Over and Other Myths about Water in the West, publishes in September.

By focusing almost exclusively on failures and crises, he says that newspapers create a gap in the public narrative. Which is too bad, he says: “Positive messages can help people who are otherwise scared and combative about the future.”

Looking outside New Mexico, Fleck found more examples of declining water use—and of people coming together to work cooperatively. “I started to see all these places where, in the midst of the risk of crisis, people are slowly and quietly adapting,” he says. “But that doesn’t get as much attention—because it’s slow and quiet.”

Moving last year from the Journal Center to an office at UNM, Fleck finally found his sweet spot. He no longer had to focus on crisis. And he could turn his attention fully toward a river he’s loved since childhood: the Colorado River, where seven states share water under an agreement signed nearly a century ago.

While researching his book, Fleck started off curious about what happens when there’s not enough water; relying heavily on water stored in reservoirs, by the late 1990s states were using more water than actually flowed through the Colorado annually.

He ended up surprised by how well people work together to avoid a crisis. Reinforcing relationships outside the negotiating room is important, he says. That’s in part because in this new era of scarcity, the old rules and the old battle lines don’t hold up very well.

One story Fleck loves to tell involves a raft and two Colorado River foes: an environmental advocate and the general manager of the Central Arizona Project, which moves more than a million acre-feet of river water through the desert in canals and pipes. Dueling from opposite ends of the water wars, the two had been quoted in the same newspaper articles. But before that rafting trip, they’d never actually met in person. Afterwards, they crafted ways to protect Mexico’s Cienega de Santa Clara from the impacts of a desalination plant. People would still get their water. But an important watershed, one that supports migrating birds and wildlife at the lower end of the Colorado, wouldn’t be destroyed.

A rafting trip—or something simpler, like a drink together at the bar or a shared meal—might not seem like a big deal. But when formal relationships strengthen, evolve, or cross institutional boundaries, Fleck thinks people better understand what the others want and value when they’re sitting around the negotiating table.

As drought has further deepened the gap between water supply and demand on the Colorado, states and water users may be facing dire challenges. And yet, there are flickers of hope within the gloom of crisis.

Children of San Luis Río Colorado play in the Colorado river. Photo by Raise the River.

A few years ago, for example, more than a dozen U.S. and Mexican agencies, as well as environmental groups, cooperated to deliver water to cities and farms during a drought – and also open the gates of Morelos Dam on the U.S.-Mexico border. That pulse of water would mimic the spring runoff rivers naturally experience when their waters aren’t dammed, diverted, and siphoned into taps and irrigation canals. In other words, water managers would allow the lower part of the Colorado to act like a river, rather than just a channel that delivers water for human needs.

It was a historic event. Since the 1960s, the river hasn’t typically reached the sea.

Greedy for water after decades dry, the channel sucked up most of the water before it made it to the ocean. But even after the eight-week long pulse moved through, scientists continued studying how the delta responded: they monitored where plants grew and survived, how that stream side habitat has affected birds and wildlife, and how the return of freshwater affected the groundwater.

With all that information, they’re learning more about the Colorado and its delta—and how future spring pulses or supplemental water releases might help the system and its wildlife even more.

Fleck and others watch the San Luis Río Colorado pulse. Photo by Raise the River.

Fleck still grins and waves his arms when talking about watching that water spread and fill the sandy channel two years ago. Activists, scientists, and officials from the US and Mexico peered over the bridge. And in the community of San Luis Río Colorado—a community still named for a river that no longer flowed past—people celebrated the water’s return. Families dragged lawn chairs and coolers to the riverbank. Kids threw up their arms and jumped into the water.

“It was made possible because all these people were working together for years,” Fleck says. “This collection of humans were all excited that they had done something people thought couldn’t be done.”

To see a video about the pulse flow and some of the studies being done, visit: http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/details.cgi?aid=10280

Dave – Thanks for the kind words. It wasn’t the Journal placing limitations on me, as much as it was me running up against the inherent limitations of the medium itself. The Journal actually gave me a really long leash, for which I will be forever appreciative. But once I started teaching and working on the book, I was finding a level of depth that is simply impossible in a newspaper form.

John Fleck was about the last reason to read the ABQ Journal. With its conservative drumbeat and recent conversion to an obituary publishing concern, I wonder why I ever pick it up.

John’s blog can be found at http://www.inkstain.net/fleck/.

A great piece about a great reporter. Kudos to both Laura and John.

But what embarrassment for the ABQ Journal!

They employed one of the country’s best-informed writers on one of their readers’ biggest, most immediate and most perennial concerns, water resources for New Mexicans and applied ridiculous, arbitrary restrictions on how much he could share with readers.

Was there nowhere in the newspaper to accommodate articles beyond 750 words; no space for even a monthly column, perhaps on Sunday, which allowed Fleck to sophisticate and balance his reports covering both threats and solutions?

John Fleck’s students at UNM benefit from his relocation, and book-readers anxiously await publication of Water Wars, but Journal subscribers receive a paper more and more suited to wrapping minnows.

or, more appropriately, for wrapping invasive European carp.