SAN JUAN COUNTY, Utah – A steep rock ledge, known locally as Ruin Point, stands sentinel over public lands rich with Native American antiquities preserved from the sands of time.

More than 700 years ago, ancestral Puebloans incised images of mountain sheep into sandstone faces now visible from dusty roads carved into canyons. Pieces of red and black-on-white pottery are scattered about snowy mesas, along with ancient corncobs and stone tools. Cliff houses wedged into crevices hide in plain sight, the blocks and mortar used to craft them blending seamlessly into steep stone walls.

Now, the 13,000-year-old historical record of Native Americans who inhabited the outskirts of two national monuments near the Colorado-Utah border is facing an unprecedented threat. On March 20, the federal government is scheduled to auction off almost 41,000 acres in southeast Utah to oil and gas companies under expedited lease sales ordered last year by Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke.

Steven St. John for Reveal

Ruins of ancient dwellings near the Utah-Colorado border sit on a mesa overlooking parcels in San Juan County, Utah, to be auctioned by the federal government March 20 for oil and gas exploration.

Just last week, Zinke abruptly postponed another lease sale – about 4,434 acres in New Mexico, including acreage on the cusp of a 10-mile buffer around Chaco Canyon, within the Chaco Culture National Historical Park. He acknowledged concerns that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, an Interior Department agency, failed to complete scientific studies it promised to archaeologists and Native Americans.

But the much-larger Utah sale remains on track, and it involves public lands home to even more fragile artifacts, archaeologists say. Among the sites to be auctioned off are the most archaeologically rich parcels ever offered for industrial use.

The Trump administration’s push to lease these public lands – which were deferred from auction under the Obama administration – would mean that archaeologists and Native Americans will not have a chance to fully document what’s at stake.

“I don’t know any other place in the world where you could go out and walk carefully along a square mile of ground and find 100 sites,” said Jim Allison, an associate professor at Brigham Young University in Utah, who’s conducted extensive archaeological research in the region.

“There are so many sites, it would take an army of archaeologists decades to map them,” he added. “We know enough to say site densities are so high, they shouldn’t do oil and gas extraction there.”

Steven St. John for Reveal

Bighorn sheep incised into stone faces more than 700 years ago by ancestral Puebloans are visible from dusty roads carved deep into Utah’s canyons.

The BLM – which manages nearly 950 million surface and subsurface acres, primarily in 12 Western states – is in charge of leasing land to oil and gas companies. Under its regulations, the BLM must conduct environmental reviews, seek public comments and address protests before auctioning off land to the highest bidders.

About a year ago, President Donald Trump issued an executive order to relieve the energy industry of “regulatory burdens.” In response, the BLM has expedited lease sales without analyzing all available cultural resource data and has canceled studies that were initiated under the Obama administration to better understand the location of antiquities and to place such lands off-limits to drilling.

A recent BLM memo directed regional managers to truncate scientific review and public comment periods and granted permission to eliminate them altogether if a proposed lease area had been studied previously.

An investigation by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting found that the administration’s expedited move to open these public lands to energy exploration puts at risk scores of ancient buildings, vessels, petroglyphs, even roads.

An analysis of hundreds of pages of federal documents, protest letters and memos and interviews showed the BLM failed to meet its obligation to identify historic properties that might be affected. Among the findings:

- The BLM’s reviews did not adequately use data from state-of-the-art studies – funded by taxpayers – that revealed potential for uncatalogued sites. As a result, the agency “grossly understates the likelihood of historic properties,” according to a written protest by the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

- Native American descendants of ancestral Puebloans said the agency did not properly consult with them before it announced the lease sales, as required by the National Historic Preservation Act.

- The BLM failed to consider information from National Park Service scientists that showed industrial activity can be seen from 35 miles away and would endanger Hovenweep National Monument’s status as an international dark sky park. The park service said this designation should have been analyzed in environmental reviews.

- The BLM found drilling roads could provide access to looters and generate dust that could harm sensitive rock art, yet its analysis states the impacts “do not reach the significant, or adverse effects, threshold.”

- Artifacts in the Four Corners region are largely unknown and unstudied because thousands of sites are not documented. Nearly 1,000 new archaeological sites were discovered in fiscal year 2017 alone on 22.9 million acres that the BLM oversees in Utah.

Descendants of the ancient peoples who called this region – known as the Colorado Plateau – home worry that the lease sales will destroy what remains of their heritage.

More than 20 tribes and Pueblos in Utah and New Mexico consider the land and artifacts on it to be a sacred historical record to pass down to future generations, said Theresa Pasqual, a Pueblo consultant who has a direct-descendant connection to Chaco Canyon.

“We know none of these places exist in isolation. Chaco is part of a much greater network that connects us to … Hovenweep,” she said. “This unfettered development, which doesn’t seem to have any kind of checks and balances on it, it’s moving forward at such a rate, it is eating up much more landscape than we can begin to understand.”

Steven St. John for Reveal

Part of the postponed New Mexico lease sale would have taken place on the outskirts of a buffer around the Chaco Culture National Historical Park’s massive, intricately crafted 1,200-year-old stone houses.

The past – and pump jacks – echo across Utah

On an overcast February day, rocks skittered to the valley floor below as Josh Ewing worked his way across a ledge in Utah’s Montezuma Canyon. Pausing, Ewing steadied his camera to photograph dancing kachinas, or images of spirits, etched into cliffs more than 1,000 years ago, a few hundred yards east of a horse with a flowing mane crafted by Ute people several centuries ago.

The panel is included in a BLM lease parcel and is one of about 60 panels the agency did not fully analyze in its report for the sale March 20, said Ewing, executive director of Friends of Cedar Mesa, founded by a retired BLM river ranger. The nonprofit is a consulting party to the lease sale.

“We have hundreds of rock art sites in the 11 leases we are protesting,” Ewing said.

Steven St. John for Reveal

Josh Ewing, Friends of Cedar Mesa executive director, photographs spirals, lizards and human figures on a newly discovered rock art panel in Utah’s Montezuma Canyon.

Several areas up for lease are within 3 miles of Hovenweep National Monument and a half-mile of Canyons of the Ancients National Monument.

On just one parcel, 51 items, including rock art panels, scattered artifacts, a masonry cliff house and petroglyphs, were listed in a Jan. 5 BLM report.

Ewing parked the nonprofit’s dusty SUV, taking care to avoid stepping on ceramic pottery pieces at Three Kiva Pueblo, which is within a parcel to be auctioned. The 14-room site features a 1,000-year-old underground kiva, or spiritual room, reachable via a wooden ladder.

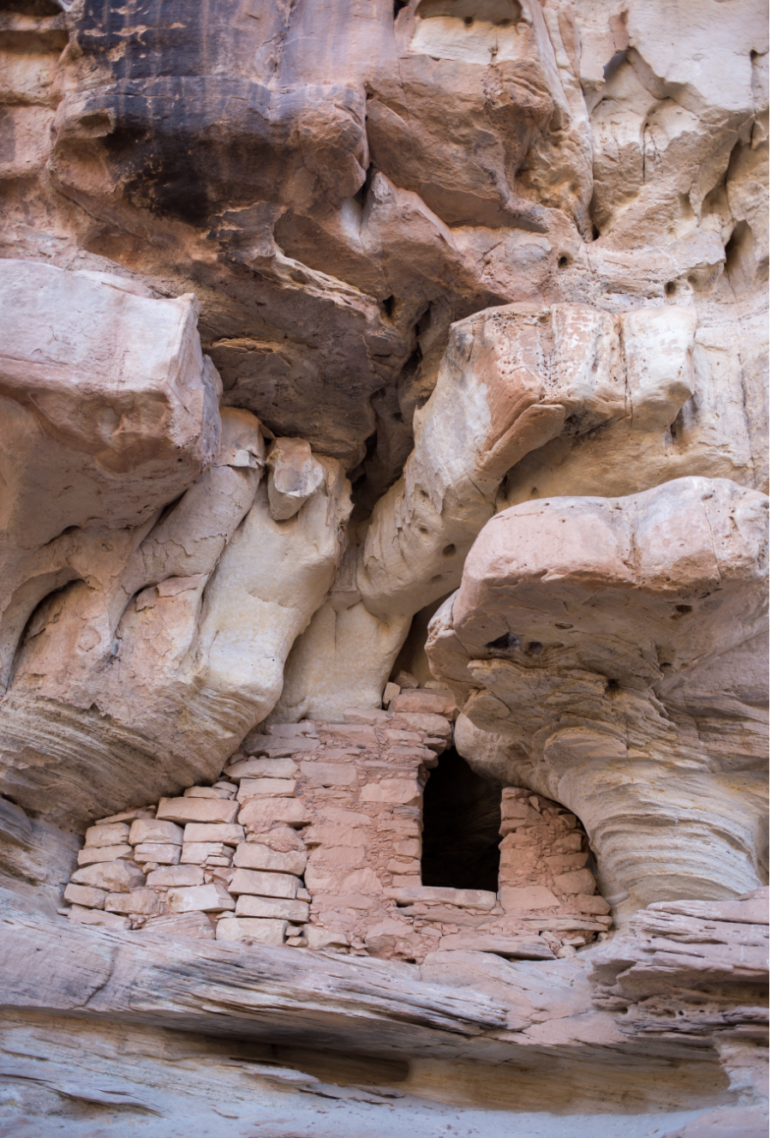

Around the corner, wedged under a rock ledge, is a granary. Red mortar that binds its sandstone blocks together still bears impressions of corncobs used to cement it in place.

About 12 miles from Three Kiva Pueblo, Ewing tiptoed around sensitive plants on Alkali Ridge. Nearby lay ruined walls that once supported more than 50 rooms in an area the BLM has designated as requiring special management attention. Now, several lease parcels are within its boundaries.

Acres used by ancestral Puebloans for dryland farming, with a 360-degree view of the Abajo Mountains and Colorado’s Mount Sneffels, were among parcels that the Obama administration deferred from leasing in 2015, citing concern about unknown cultural resources. The lease sale under the Trump administration includes even more antiquities, Ewing said, as a beat emitted by a pump jack echoed across the sagebrush plains.

“With Trump, they’re doing a significant U-turn,” he said.

Steven St. John for Reveal

A cliff dwelling preserved for millennia by the dry high-desert climate is included in a March 20 lease sale for oil and gas companies in southeast Utah.

In protesting the sale, Hopi Cultural Preservation Office Director Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma wrote to the BLM that “commingling of areas of high densities of prehistoric sites significant to the Hopi Tribe with energy development will lead to adverse effects to those prehistoric sites.”

The BLM did not respond to a detailed list of questions from Reveal about the lease sales.

Under the Obama administration, Interior Secretary Sally Jewell brought together conservationists, residents and scientists to map sensitive areas that should be off-limits to industrial activities in what’s known as master leasing plans. More than a dozen such plans were initiated, including one around Moab, Utah. The BLM under Trump has eliminated such plans, quashing similar efforts, which are designed to balance drilling and cultural resource protection, underway in Utah and New Mexico.

Kevin Jones, who was Utah’s state archaeologist for 17 years, from 1994 to 2011, called the BLM reviews inadequate. Only 5 to 10 percent of the state has been surveyed for archaeological relics, he said.

“The BLM does a cursory review of what is known about these sites and makes a determination – could a maximum number of wells be placed on property without unduly impacting cultural resources? – then they make a guess based on very little information,” Jones said. “Unfortunately, it ends up causing a lot of damage.”

Sacrificing science for streamlining?

Within the proposed parcels, between 2 and 55 percent of the ground has been surveyed, the BLM wrote in its November environmental assessment. About 1,300 archaeological sites have been documented there, 937 of which are eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Steven St. John for Reveal

Acres of land used by ancestral Puebloans for dryland farming were among parcels that the Obama administration deferred from leasing in 2015. But they are now part of the Trump administration’s March 20 lease sale.

Holes in the archaeological record mean that oil and gas companies are likely to encounter some cultural resources when they build roads, pour well pads and haul equipment in and out of the fragile desert landscape, said Donald Simonis, an archaeologist who retired in 2016 from the BLM’s Monticello office, which oversees leasing in southeastern Utah.

BLM officials said in documents that they would require detailed analysis of sites after leases are auctioned. Whenever an energy company applies for a drilling permit, it must hire an archaeologist to walk the site. “Appropriate mitigation (measures) would be applied” then, the BLM wrote.

The agency stated there is ample room in the Utah parcels to separate drilling from cultural sites.

“While sites potentially sensitive to indirect and/or cumulative effects are present, these effects can be avoided through judicious placement of a well within this large, topographically complex parcel,” the BLM wrote.

Energy industry representatives say their companies are at the forefront in protecting antiquities.

Steven St. John for Reveal

A pump jack on Alkali Ridge emits a beat that echoes over a region rife with historically notable Native American antiquities. Archaeologists say the lease sale is occurring without adequate review of cultural artifacts.

“When a company acquires a lease, they have to spend those resources, whereas government or scientific groups don’t do it,” said Kathleen Sgamma, president of the Western Energy Alliance, a trade group that represents more than 300 companies that produce oil and gas. “We know more about archaeological resources in the West because oil and gas companies go out and do surveys.”

If companies do find something, Sgamma said, they must report it to the BLM and adjust their drilling plans to protect views and soundscapes.

But archaeologists and advocacy groups worry that at that point, it’s too late to protect sensitive parcels, given that a company already holds a legal right to use the land. And even if scientists clear the parcel for drilling, it’s likely they will miss something, Simonis said.

“Sometimes it’s hidden a quarter-inch below the ground,” he said. “Many times in my career, I said, ‘Sure, go out and do the project,’ and they go out there and bones and pottery and everything else starts popping up.”

Chaco: America’s ‘medieval castles’

On U.S. Route 550 in New Mexico, semitrailers filled with water and sand for hydraulic fracturing speed by drilling equipment that surrounds a one-mile turnoff sign for the Chaco Culture National Historical Park.

Over the hill, flares from oil and gas wells slice 15 feet into the brisk January air. The fires are visible from the UNESCO World Heritage Site’s visitor center 36 miles south. Members of a nearby Navajo community say industrial activities are permanently scarring a region that birthed their culture.

Steven St. John for Reveal

Archaeologist Paul Reed hikes among ruins at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park, pointing out areas outside the park that are unprotected.

“This is our holy land – it’s the place of emergence where our most sacred ceremonies were created,” said community leader Daniel Tso. “It’s being inundated with oil and gas wells.”

Energy companies plumbed New Mexico for a half-century. But never had a lease sale come so close to Chaco as the one Zinke just postponed, citing concerns from tribes, archaeologists and Utah senators.

“I’ve always said there are places where it is appropriate to develop and where it’s not. This area certainly deserves more study,” Zinke said in a statement.

The BLM had failed to complete a report listing where artifacts could be located, which was promised to archaeologists and Native Americans by early January, said Paul Reed, an archaeologist with Archaeology Southwest, which was a consulting party to the sale.

Tribes that trace their ancestry to Chaco’s inhabitants say the agency did not consult with them before finalizing that now-postponed lease sale.

“Tribal consultation starts with a blank sheet of paper; it doesn’t start at the tail end when you’ve devised your plans,” said Tso, gesturing to pipelines that interrupt foraging grounds for the tribe’s free-range cattle.

Navajo community leader Daniel Tso is concerned about the effects of oil and gas development in northern New Mexico on land considered sacred.

Part of the lease sale would have taken place on the outskirts of a 10-mile buffer created during the Obama administration around Chaco’s massive, intricately crafted 1,200-year-old stone houses.

Scientists debate whether the hundreds of rooms at Pueblo Bonito, the best-known great house at Chaco, were used for ceremonies, living areas, commerce or a combination of all three.

“This isn’t the Statue of Liberty, it’s not Mount Rainier,” Reed said as he pivoted backward through one of Pueblo Bonito’s signature T-shaped doorways. “We have 200 pieces of the puzzle, but we’ve lost the box top.”

Clans that built the 40-foot-high structures cut millions of stones and dragged ponderosa pine 50 miles from the Chuska Mountains. They employed techniques never seen before Chaco’s rise in the 800s, nor after its depopulation in the 1200s.

Most of Chaco’s 200 outlier sites remain unprotected outside the park, including several that sit in a proposed lease on Utah’s Alkali Ridge. To orient Chaco with these outliers, Reed scampered up a perilous ancient staircase to a mesa with panoramic views.

“There on the skyline is Pueblo Pintado. Like others here, it’s reminiscent of a medieval castle – built to be seen from 5 miles away,” Reed said.

He pointed to the faint outline of the arrow-straight, 30-foot-wide Great North Road, which travels over mesas and cliffs to Kutz Canyon 31 miles away. The road runs adjacent to acreage that was to be included in the postponed lease sale.

The byway puzzles scientists, who recently discovered new segments using a technology called light detection and ranging, or Lidar. Mounted on aircraft, the remote sensing method uses laser pulses to measure the distance to surfaces below, allowing scientists to detect things that aren’t visible from the ground.

“The ancestral Puebloans put such an investment in construction and engineering of these roads,” said Anna Sofaer, founder of the Solstice Project, who worked on the Lidar study. “We are just at the tip of the iceberg in documenting them.”

High-tech data hasn’t been analyzed

Data on the new roads is part of roughly 1,600 square miles reviewed using Lidar in areas around Chaco. This data hasn’t been fully analyzed and wasn’t incorporated into BLM studies for the lease sale, Reed said.

Using remote sensing techniques, Binghamton University anthropology professor Ruth Van Dyke found a site beneath the surface of tribal land that collapsed from the weight of oil and gas activity. She also made a discovery within the Chaco park with sensitive instruments that react to archaeological material.

“Just last summer, we found four or five (underground) buildings,” she said. “We had to cut it short; we ran out of time and money, and the buildings just kept going.”

The BLM estimated 278 unrecorded sites could exist in parcel areas that have not been inventoried. But the agency concluded that disturbance of these sites was unlikely because its data shows “one discovery per 5,472 acres.”

Steven St. John for Reveal

A gas flare rises about 15 feet into the air about 35 miles northeast of Chaco Canyon.

Reed doubts this conclusion. An hour’s drive north of Chaco, he lost his way several times looking for Pierre’s Complex, a Chaco outlier site. One of the leases in the postponed sale sits several thousand feet northwest of Pierre’s Complex and just beyond Chaco’s buffer.

Parking near a pump jack less than 1,000 feet from the ruin, Reed double-timed it through desert sand, then stopped to peer up at the remains of “El Faro,” or “The Lighthouse.”

“This is the poster child for a site that’s been protected by the tools the BLM has in place,” Reed said.

A pump jack in the valley below hammered out a rhythmic cadence. At least a dozen pump jacks around Pierre’s Complex have destroyed the sense of place a Chacoan would have experienced here.

“Each archaeological site is a one-of-a-kind record of some important happening,” said Jones, Utah’s former state archaeologist. “Every time we wreck one, we lose an important chapter from that human story.”

This story was produced by Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, a nonprofit news organization. Learn more at revealnews.org and subscribe to the Reveal podcast, produced with PRX, at revealnews.org/podcast.