This year’s chile season is in full swing, but it is getting mixed reviews from farmers in southern New Mexico.

Maria Martinez sells her family’s produce from Anthony and Brazito on Wednesdays and Saturdays at the Farmers and Crafts Market in Las Cruces. Her booth stands out with red chile ristras strung up around the sides and sacks of chile piled next to them. Fresh green chile fill baskets at her booth and a continuous stream of customers approach her during the market, searching for their chile fix.

She said it’s been a struggle this year because of insufficient water.

“It’s been kind of hard because they don’t give them much water,” Martinez said of the local irrigation district.

Dino Cervantes, of Cervantes Enterprises Inc. and a board member of the New Mexico Chile Association, grows cayenne peppers and jalapeños in Vado. He was only about 10 days into harvesting, he told New Mexico in Depth in early September, which is late for the season.

“It’s like the whole year is almost a month behind,” he said.

Climate change is likely to produce more dry years and more unpredictable growing seasons for farmers in southern New Mexico, as temperatures increase and the snowpack in northern mountains continues to decline.

Dry years aren’t new in the arid Southwest. Historical data show farmers in the region have over the last century weathered sustained dry spells that alternated with wet periods, including long stretches of drought.

Debra Peters, lead research scientist with the Jornada Experimental Range, said during a presentation last week at New Mexico State University that drought is habitual to New Mexico, based on over 100 years of collected data. She defined drought as four or more consecutive dry years.

“It’s very characteristic of some arid regions — about every 20 or every 50 years, you have a drought,” Peters said.

But New Mexico’s farmers face increased uncertainty in the future due to climate change. A question mark hanging over their heads is how steadily increasing temperatures will disrupt historic patterns, leading to more dry years in the future.

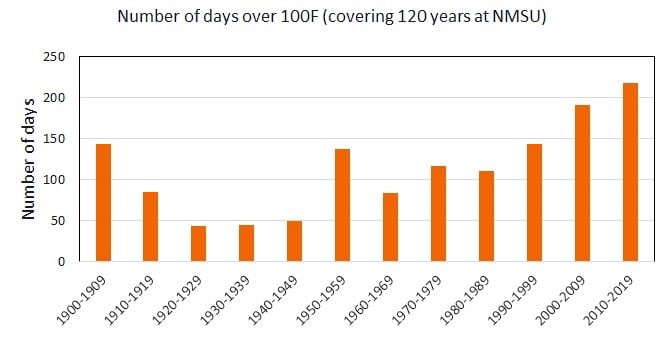

David DuBois, New Mexico climatologist, said this August was the second hottest on record, out of 120 years New Mexico State University has been gathering that information. It’s not a new phenomenon. He explained that temperatures have been increasing since the 1970s.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the average temperature in New Mexico has risen two degrees since then.

“That’s the fingerprint of climate change, is making something a bit worse over time,” DuBois said. “And then it’s just going to keep climbing if our projections are right. Climbing temperatures or droughts are going to be hotter, which in some cases that’s even worse than less water.”

DuBois said the increased heat causes more heat stress, leading irrigated plants to require more water.

“It’s called evapotranspiration, so that means they lose water every day,” DuBois said. “And so in order for them to be healthy, you have to add water, more irrigation.”

The one thing New Mexico does not have is more water.

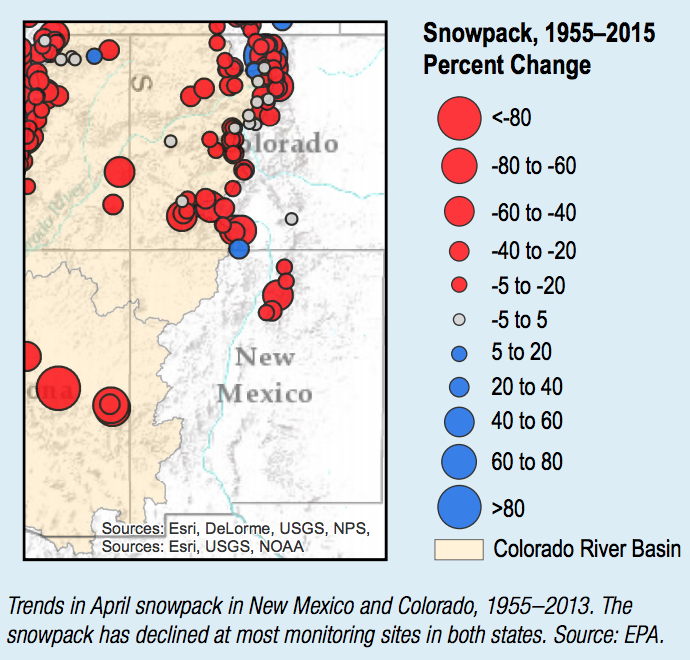

The water delivered by the Rio Grande to Elephant Butte reservoir largely comes from snowpack high in the southern Colorado and northern New Mexico mountains. That snowpack has been declining for decades, and melting faster.

Farmers in the Mesilla Valley this year grappled with less water due to a long, dry 2018 that saw little snow and Elephant Butte reservoir reduced to just 3 percent capacity by September. Elephant Butte Irrigation District didn’t release water for irrigation this year until early June.

Gary Esslinger, manager of the Elephant Butte Irrigation District, which provides water to southern New Mexico farmers, said the lake has a capacity of over 2 million acre-feet. In the 1970s and 1980s, the lake held around 790,000 acre-feet, allowing the water to flow down the Rio Grande from February to October. Esslinger said from 2003 to today, the water runs for only about 67 days.

EBID issued a grim outlook for 2019 just as the year kicked off, cautioning farmers they’d only receive four to eight inches of water per acre. It turned out a lot better, farmers received 14 inches. Still, that’s just a fraction of the water they’d receive in a good year.

Cervantes said in drought years, his farm pumps groundwater to supplement surface water received from the Rio Grande.

That pumping is a sticking point with water users further downstream in Texas and is an instigating factor in a Texas vs. New Mexico and Colorado water lawsuit that has the potential to make the state’s water situation even more precarious. Farmers throughout the Mesilla Valley rely on groundwater pumping in dry years.

But pumping isn’t always a solution. The Martinez family have a pump but this year the supplemental water didn’t save many of the plants from dying.

Cervantes said farmers adjust to water shortages by changing how often they water or using different forms of irrigation, such as drip irrigation and micro sprinklers, to extend the amount of water they have. Other options are to change their crop rotation, grow less water-intensive crops or farm less acreage.

“Farmers, they just adapt,” Cervantes said. “I don’t know there’s really a normal year, so every year presents its challenges. You kind of play the hand that you’re dealt and do the best you can with it.”

The good news for farmers like Cervantes and Martinez is an end of season announcement by EBID forecasting an early spring start to the irrigation year in 2020.

This story is part of New Mexico In Depth’s partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Leah Romero is New Mexico In Depth’s academic fellow at New Mexico State University for the 2019/2020 school year.