A short exchange at Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s town hall last month captured the magnitude of the mission New Mexico is on as it seeks to remake public education.

A mother, a recent transplant to Albuquerque from Gallup, told Lujan Grisham that school officials said her 8-year-old autistic daughter couldn’t learn Navajo.

“Because it would confuse her,” the woman said, confessing the information hurt and angered her.

“This has been going on for years and years and centuries with our culture,” the speaker said into a microphone so she could be heard by the crowd and those listening online. “I want her to learn who she is, where she came from and her identity and growing up and being proud of who she is.”

The woman’s complaint could have been lifted from a 2018 court ruling that these days is forcing New Mexico to invest big in educating students who’ve historically gotten less. Noting federal and state governments’ forced assimilation of indigenous children over centuries, the late state Judge Sarah Singleton said the practice led to a “disconnect from and distrust of state institutions, such as public schools, where Native American values are not respected.”

Lujan Grisham acknowledged to the woman the state’s imperfect lurches toward improvement as New Mexico tries to overturn decades of policy and funding decisions to better educate at-risk students, most of whom are from communities of color.

The state is struggling “to get the cultural and linguistic requirements of every student met” despite increasing funding for Native American students, the governor said.

“The fact that we are not doing it for you means that we have to provide more support for your school, to you and to your daughter,” Lujan Grisham said before encouraging the speaker to meet with her Education secretary, Ryan Stewart, who sat a few feet from his boss on stage.

The moment showcased one New Mexico family’s obstacles and served as a reminder that stories such as these likely aren’t rare in a state where a majority of the state’s public school students qualify for at least one risk factor.

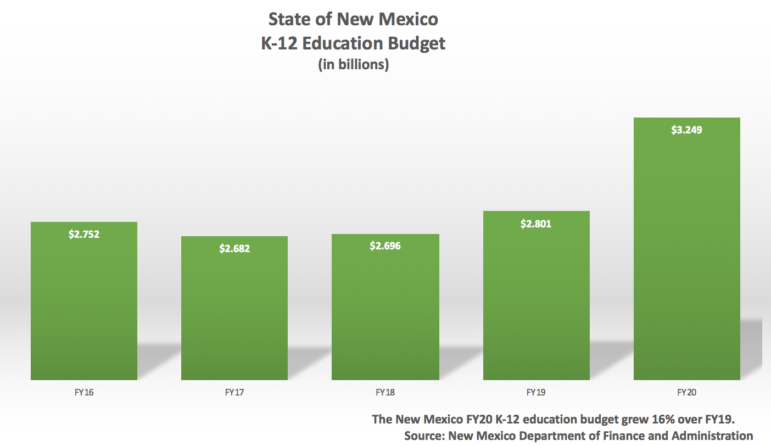

Lujan Grisham and state lawmakers return to Santa Fe this month with that reality in mind after pumping a half a billion additional dollars last year into the public education system, which takes up nearly half of the state budget.

“A step toward our moon shot,” the governor called the investment.

Half a billion dollars comes with expectations, but as policy makers, lobbyists and elected officials often observe, big change takes time. And in this case, the change is big not only because it’s decades overdue, but also because policy makers say it requires both sweeping vision and a penchant for the meticulous – an ability to see two generations into the future while remembering people in the here and now, like a woman telling you how the current system is letting down her 8-year-old daughter.

“We want to know as many specifics about” your daughter’s situation, the governor said to the woman. “It is an area that is going to require a lot of attention.”

Everyone agrees 2019 wasn’t a case of one and done for education, and Lujan Grisham has an ambitious agenda for the 2020 session, as do top lawmakers.

The governor is supporting an idea to create a trust fund for the state’s 123,630 children under age 5 to help pay for preschool, home visiting and early intervention programs for children with disabilities. She’s pushing for a one-time $320 million appropriation.

She also wants to make college tuition free for New Mexicans, an idea that generated whoops and cheers from the town hall crowd.

And her administration wants to diversify the state’s teaching ranks, she said, to include more Native Americans and those who speak more than one language. According to findings in the 2018 Yazzie/Martinez court case, fewer than 2% of teachers in the state’s public schools are Native American compared to the nearly 11% among students.

“You don’t have enough Hispanic educators, don’t have enough male educators,” the governor said at the town hall. “Then you need to make sure you are making those investments” to spread opportunity around so that “our educators will come from the same cultural backgrounds and will relate to their students and vice versa.”

Meanwhile, top lawmakers hope to increase educators’ salaries again as they did in 2019 to cauterize the state’s chronic teacher shortage.

“We are not attracting enough teachers,” said Senate Majority Whip Mimi Stewart, a retired educator from Albuquerque who added there were 644 openings around the state.

There will be a push to invest in quality housing for educators working in majority Native, mostly rural school districts, too, to try to stem the high staff turnover, said House Speaker Brian Egolf, D-Santa Fe.

Egolf and the House budget committee chair, Rep. Patricia Lundstrom, D-Gallup, also hope to boost the bottom line for some of those low-income districts by letting them keep more federal dollars called “impact aid,” which assists local school districts that have lost property tax revenue because of the presence of tax-exempt tribal or federal lands.

Currently, the state runs much of those dollars through a state equalization formula, and then disperses it around the state to other districts, including much wealthier ones than those that triggered the federal aid in the first place.

The equalization formula was created in the mid-1970s to ensure all students have equal access to programs and services regardless of geographic location or local economic conditions. Rolling the federal impact aid money into the formula creates an “inequity in what was an otherwise good idea,” said Regis Pecos.

A former governor of Cochiti Pueblo and co-founder of Santa Fe’s Leadership Institute, an indigenous think tank, Pecos has spent decades thinking about indigenous education.

Pecos, who works as the chief policy adviser for House Majority Leader Sheryl Williams Stapleton, D-Albuquerque, welcomes New Mexico’s focus on educating children from the state’s low-income communities of color. But it’s not a new problem, he said.

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Kennedy Report, a federal review of indigenous education that acknowledged the classroom was a tool of assimilation for indigeneous children for much of this country’s history. To emancipate “the Indian child from his home, his parents, his extended family, and his cultural heritage,” as its authors wrote.

A perusal of the more than 3,000 findings of fact from the Yazzie/Martinez court case puts in relief the obstacles policy makers must contend with as they seek to reform a system centuries in the making.

For instance, in recent years, teachers with language certificates in school districts with high concentrations of Native American students refused to teach indigenous youth learning English because they believed low test scores might “negatively affect their teaching evaluations.”

Meanwhile, most Native American English learners in six school districts with high concentrations of indigenous students were placed in remedial reading rather than given dual language or bilingual programs that are considered the gold standard for teaching English learners.

Pecos hopes the state continues to invest big in education in 2020, but with a holistic view that accounts for history and addresses economic and educational injustices. One that recognizes that salaries will only go so far in reforming the system. There must be well-thought-out strategies to produce more indigenous teachers and give more communities flexibility in curriculum, and on and on. It’s not one thing, but many, he said.

“It is no longer about a legal obligation or the test of political will,” Pecos said. “This session will be a defining moment of our collective moral character to do the right thing.”