Redistricting

Lawmakers protected themselves when redistricting, report finds

|

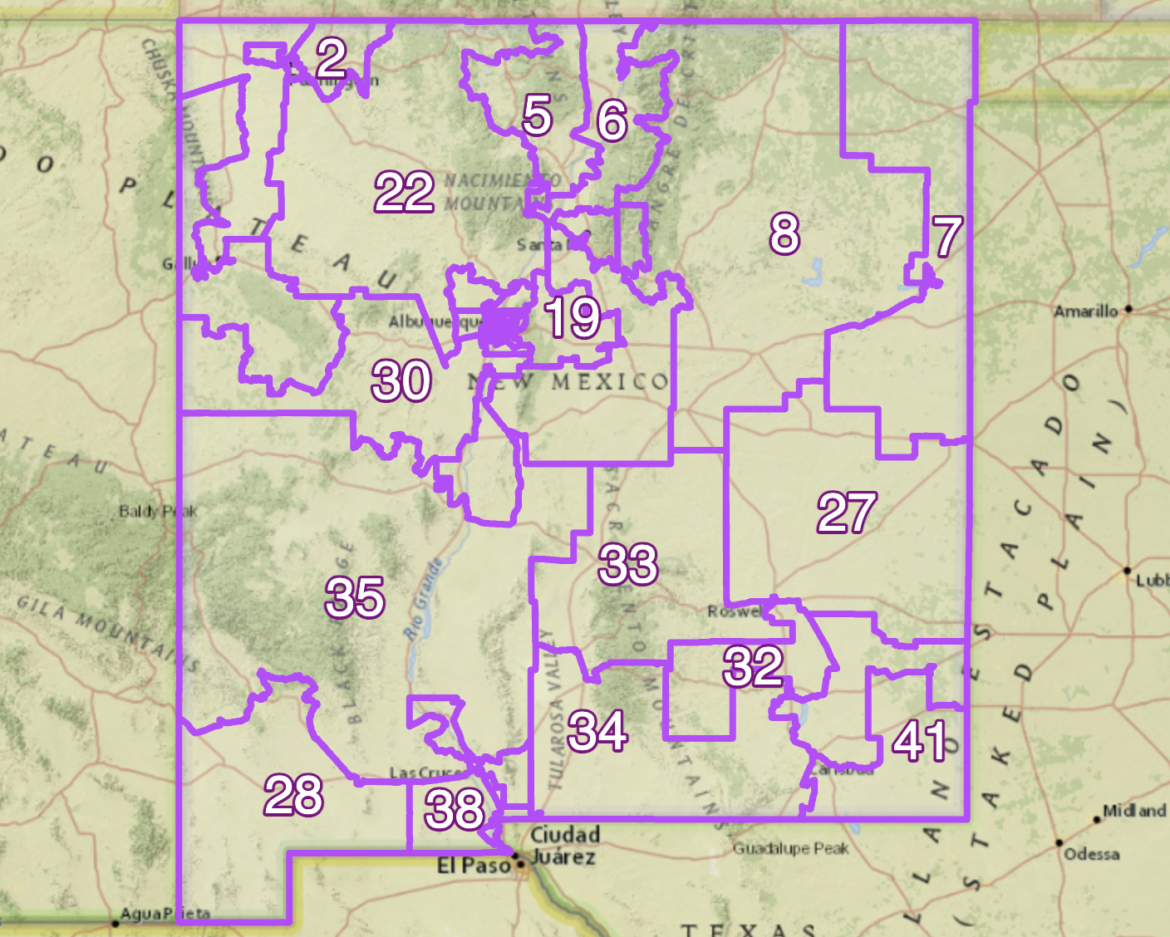

New Mexico lawmakers protected themselves and their colleagues when they redrew political district maps crafted by a 2021 nonpartisan advisory commission, shielding incumbents of both parties from competition and making legislative elections less competitive, according to a new 59-page report co-authored by University of New Mexico political science professor Gabriel Sanchez. The study, released Sept. 28, found no evidence that New Mexico Democrats, who have strong majorities in the House and Senate, politically gerrymandered their districts, a conclusion based on statistical analysis conducted by Sanchez’s co-author and University of Georgia professor David Cottrell. “The protection of incumbents was the greatest source of gerrymandering this session,” the authors concluded, based on the analysis and interviews with experts. That outcome resulted from inherent weaknesses in how lawmakers set up the state’s new Citizens Redistricting Committee – the committee doesn’t have final say on what redistricting maps are adopted, the report found. State lawmakers crafted districts in which far fewer sitting legislators would have to run against each other, compared to districts created by a computer program used in the study that did not take into account where incumbents live.