As drought tightens hoses in California and a lawsuit heats up between Texas and New Mexico on the Rio Grande, it’s tempting to think that the 21st century’s water battles are somehow novel. But they’re not. As the history of water rights and big ideas for dams on the Gila River shows, some decades’ old court decisions, laws, and backroom deals are still playing out today.

As drought tightens hoses in California and a lawsuit heats up between Texas and New Mexico on the Rio Grande, it’s tempting to think that the 21st century’s water battles are somehow novel. But they’re not. As the history of water rights and big ideas for dams on the Gila River shows, some decades’ old court decisions, laws, and backroom deals are still playing out today.

The 1930s and ‘40s: Establishing water rights within New Mexico

Just a few years before World War II, the US District Court established the water rights of New Mexico and Arizona on the Gila River. That is, it decided how much water people could take based on the river’s natural flows, how much could be stored in reservoirs, and who had “priority”—or the right to take water before someone else. Called the Globe Equity No. 59, that 1935 decree is still important today. It also offers a record of the river and how people have put its water to work.

As Ira G. Clark writes of that decree in his 1987 book, “Water in New Mexico: A History of Its Management and Use,” fixing those priorities was important because “the flow was frequently too small to give all appropriators the amount of water to which they were entitled.”

By that time, the federal government had already dropped plans to build a dam on the Gila. In 1916, the US Bureau of Reclamation found the river wouldn’t support a planned hydro-electric dam. And in 1928, Reclamation abandoned another survey, finding that the Gila’s flows were too meagre to support its existing users, nevermind new ones. Plans for dams, however, continued to be floated throughout the 20th century.

Thanks to the Globe decree, at the beginning of each year a court-appointed water commissioner would evaluate how much water was in the Gila and its reservoirs, and how much water each user would receive. The decree also required canal owners diverting water to install measurement devices, called headgates. Those could be regulated and locked by the commissioner.

According to Clark, New Mexico’s water users were satisfied with the decree—until the dry fall of 1938. Unhappy with the low flows, they asked the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission (ISC) for support. The ISC ordered the court-appointed commissioner to stop what he was doing. When he continued regulating diversions under the decree, New Mexico’s State Engineer threw down, declaring that a new water master operating under state law would oversee the river in New Mexico instead.

That set people off, writes Clark:

“Once this was done Virden Valley water users insisted that they were no longer under the jurisdiction of the commissioner and stopped paying the assessments for costs. The commissioner responded by locking all the headgates in New Mexico, permitting the entire flow to go downstream to Arizona. New Mexico Governor John E. Miles then asserted the right of the state to control the waters of the Gila within its boundaries and directed the New Mexico State Police to break the locks and take charge of the headgates.”

A legal battle broke out, dragging through federal court for years.

But, writes Clark, a final decision became unnecessary when Arizona and California started battling for Colorado River water in the US Supreme Court.

The 1950s and ‘60s: Fighting among western states

In the 1950s, Arizona was trying to clarify its rights to the Colorado

In the 1950s, Arizona was trying to clarify its rights to the Colorado

River, of which the Gila is a tributary.

In 1952, Arizona sued California and seven of its cities and irrigation and water districts over their use of Colorado River water. In 1922, the Colorado River Compact had divvied rights to the river’s water among seven states.

The United States, Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico were all drawn into the 1952 case, and in 1963 the Supreme Court filed its opinion. The next year, it entered a decree allocating each state its rights to Colorado River waters.

For New Mexico, that meant a clarification of its rights to the Gila, its tributaries, and associated groundwater.

In the late 1950s, New Mexico had been also intent on proving its existing rights to the Gila’s water. In 1958, what was then called the State Engineer Office took hundreds of depositions, collecting information about use of the waters and people’s priority dates. According to Clark, the commission also set aside $30,000 to work with the US Bureau of Reclamation on a report on potential water development projects for the future.

By that time, however, all the river’s waters were already appropriated. Clark writes that trying to stake a claim on water for future use was “wholly unjustified” and “it was unlikely that there was enough water to meet present needs.”

Meanwhile, Arizona had been trying to figure out how to use its Colorado River water, and move it to cities like Phoenix and Tucson, hundreds of miles away.

For years, the Arizona congressional delegation, including Rep. Morris Udall, had sought support for the Colorado River Basin Project Act, which would authorize the Central Arizona Project (CAP). That project would move billions of gallons of Colorado River water through a system of aquaducts, tunnels, and pipelines across central and southern Arizona.

Each time, however, the House Interior Committee had blocked it from a vote on the House floor. Much of the opposition centered around spending federal taxpayer money on a project that would only benefit people in Arizona.

Instead of fighting with neighboring states, Arizona was going to need allies.

At the time, New Mexico was still dissatisfied with the 1935 decree, now in place for some three decades.

According to Clark, New Mexico State Engineer Steve Reynolds claimed that it caused at least 175,000 acre feet of water to flow from New Mexico into Arizona each year. Clark writes of that water lost to Arizona: “It came from a sparsely settled and economically depressed area whose only hope for improvement was to secure enough water to develop its mineral, industrial, and agricultural potential, and to supply municipal needs.”

Reynolds, who reigned over New Mexico waters from 1955 until 1990, convinced New Mexico Senator Clinton P. Anderson to withhold support for a bill authorizing the Central Arizona Project. He wanted Arizona to agree to modify the 1963 decree so it would protect New Mexico’s claim to future water rights on the Gila.

Feelings were hurt, fights dragged on, and Reynolds continued negotiating. Finally, in 1966, he worked with the Arizona delegation and drafted an agreement giving New Mexico an extra 18,000 acre-feet of annual water rights on the Gila.

Then in 1967, for the third time in 17 years, Arizona Sen. Carl Hayden guided the Colorado River Basin Project Act through the Senate.

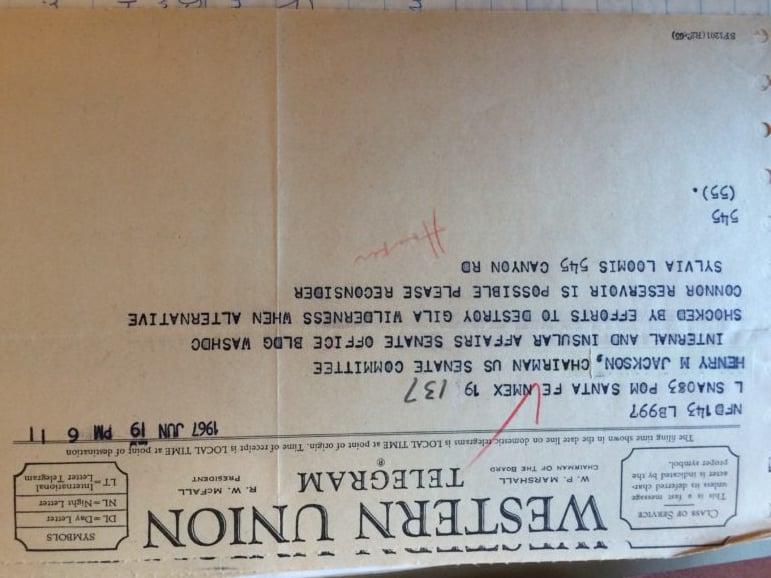

In a 1967 letter to Sen. Thomas Kuchel, R-CA, Sen. Henry Jackson, D-WA, wrote: “In the context of fairness, I think those of us who serve in this body should remember that our beloved colleague Senator Hayden deserves fair treatment after waiting nearly forty years for authorization of this project.”

But during the 90th session of Congress, Rep. Wayne Aspinall, D-CO, chair of the House Interior Committee, again refused to move the Senate-passed bill. The Colorado congressman claimed that if Arizona diverted water for CAP, it would endanger future use of the river’s water by Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

According to a September 28, 1967 document in the congressional record, when Aspinall refused to move the bill, he said he’d shut down his committee for the rest of the session. And he refused to say when, if ever, the bill would be reported to the House.

Enraged, Hayden fired back, threatening that he’d use his influence in the Senate Subcommittee on Public Works to reduce funding for a water project in Aspinall’s district. Hayden eventually backed off. But the spat shows how nasty water fights in Congress had become.

And the politicking continued. The Arizona delegation had US Department of the Interior Secretary, Stewart Udall, on board. And now, they had New Mexico’s support, especially Sen. Anderson’s.

In 1968, Congress finally passed the Colorado River Basin Project Act, which was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

It included new water rights for New Mexico—the 18,000 acre feet negotiated by Reynolds—and it authorized Hooker Dam or its “suitable alternative.” Planned for the Gila, the dam’s reservoir would back into the Gila Wilderness, the nation’s first designated wilderness area.

Once the bill was signed, Arizona got busy building the Central Arizona Project. Construction on the $4 billion project started in 1973; the finishing touches were completed in 1993.

Today, its 336-miles of canals, tunnels and aquaducts moves 1.5 million acre feet of water each year from the Colorado River to central and southern Arizona.

The ‘00s: Money talks

Meanwhile, New Mexico still hadn’t touched those extra water rights Reynolds negotiated in the 1960s.

That’s because there was one big catch: The state didn’t receive that water outright. Instead, New Mexico would have to find a downstream water user in Arizona willing to exchange water from the Gila or its tributary, the San Francisco, for Colorado River water.

For decades, New Mexico couldn’t find a willing water trade. During that time, three federal proposals for dams on the Gila were also defeated: Hooker, the original dam mentioned in the 1968 legislation; Connor Dam; and a third proposal to dam the river near Mangas creek.

Then, in the early 21st century, Arizona needed New Mexico’s big senatorial guns again.

Arizona needed federal money to settle water rights with the Gila River Indian Community. And the delegation needed help from New Mexico Sens. Pete Domenici and Jeff Bingaman to pass the Arizona Water Settlements Act (AWSA).

(Both New Mexico senators were on the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Domenici was chair during initial discussions of the act; Bingaman, when Congress passed it.)

Among other things, that 2004 law created a way for New Mexico to use its Gila-San Francisco water. New Mexico would pay an exchange fee for the Gila River water, which would allow the Gila River Indian Community, a downstream Gila River user in Arizona, to buy Colorado River water from the Central Arizona Project (CAP).

New Mexico still wouldn’t own that water outright. And the law lowered its annual allocation from 18,000 to 14,000 acre feet per year. That’s 10,000 acre feet from the Gila and 4,000 acre feet from the San Francisco.

Not only that, but New Mexico can only divert that water after downstream water needs have already been met. State officials have also said they will only take water from the river when its flows are higher than 150 cubic feet per second.

But, significantly, the 2004 law included federal funds designated for a New Mexico based project to access the Gila water.

AWSA also gave the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission ten years to decide: The state could meet water demands in Grant, Luna, Hidalgo, and Catron counties through efficiency and conservation efforts or by building a diversion project on the Gila River.

Depending on its decision, the state would receive between about $66 and $100 million from the US Bureau of Reclamation.

For years, the state held public meetings and entertained proposals. The process was largely controlled by one ISC employee, Gila Region Manager Craig Roepke, who was also a proponent for diversion.

But during the Richardson administration, it seemed likely the state would choose conservation over diversion. In 2008, Richardson even vetoed a line item in the state’s spending bill that would have allocated nearly a million dollars toward supporting a possible diversion on the Gila River.

In 2011, the New Mexico state legislature passed a bill (H.B. 301) establishing the New Mexico Unit Fund, which is controlled by the ISC. In early 2012, the US Bureau of Reclamation made its first payment of $9.04 million.

That initial money was meant for salaries at the ISC, public meetings, studies of the river and its ecology, and engineering studies of diversion proposals.

Using that money, the following year, the ISC approved 16 project proposals for further assessment—ranging from diversion and storage projects to effluent reuse and municipal infrastructure projects—and an additional study of wetlands restoration and agricultural conservation.

But by then, it became clear that under Gov. Susana Martinez’s administration, the ISC would support the diversion alternative.

In 2014, the commission considered three main diversion proposals: a $42 million project to divert water upstream of Cliff and then store it underground and in small farm ponds. A second, $500 million project would have diverted water from the Gila and stored it in off-stream reservoirs in Mogollon or Mangas creeks and then piped it 73 miles to Deming. The third proposal would have cost $235 million and moved water to Hidalgo County.

For years, people had questioned building a diversion on the Gila River. Opponents pointed to its environmental impacts and asked who would buy the water.

When the ISC released the three diversion proposals, however, opponents had new ammunition: The cost estimates were high, far exceeding the amount of money New Mexico would receive from the federal government. But they weren’t high enough.

Independent analysis of the projects—and in particular of the Deming plan—put the cost at closer to a billion dollars.

Former ISC director Norman Gaume dug in—with help from environmental groups—challenging his former agency on everything from Open Meetings Act violations and dubiously awarded contracts to cost underestimates and engineering plans that were “infeasible” given the area’s geology.

But in late 2014, the ISC voted to pursue the diversion alternative. That vote—with only one “nay” vote cast—set the state on a course to receive the additional federal funding and to start planning where and how it would build a diversion on the Gila River.

The following year, a new state agency formed, the New Mexico Central Arizona Project Entity. It works in cooperation with the Interstate Stream Commission, relying heavily on guidance from the ISC attorney and its staff, most notably Roepke. It has also hired its own attorneys, including Pete Domenici, Jr.

Each NMCAP Entity board member represents a county, city, agency, or irrigation district that has committed to planning, building, and operating the diversion. By signing on to the NMCAP Entity, those local governments have also agreed to figure out how to bridge the gap between the federal money New Mexico receives and the diversion’s ultimate cost.

When it agreed in 2014 to accept additional federal money and build a diversion, the state had deadlines to meet. The first major deadline was July 15, 2016. By then, New Mexico needed to have chosen a plan and location for the diversion. It was also supposed to submit a “30 percent design” plan to Reclamation.

In mid-July, the NMCAP Entity’s executive director sent Reclamation a two-page letter and four maps.

The proposal combines two components: A diversion at the upper end of the Cliff-Gila Valley that would feed water underground, where it could be stored and used at a later time. And a second component that would divert water from the river into a newly constructed reservoir in Winn Canyon.

Now, New Mexico has to hire consultants to help the NMCAP Entity refine the designs and peg down the exact locations. They’ll also have to begin studies required by laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the Endangered Species Act, which will require consultation with the US Fish and Wildlife Service over rare fish, bird, and reptile species in the project area.

During the NEPA process, the Bureau of Reclamation and the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission will evaluate the entity’s proposal and various alternatives, as well as their possible impacts on the environment and cultural resources.

Meanwhile, to receive the full federal subsidy, New Mexico needs to complete that work in time for the US Secretary of the Interior to issue a decision on the project by the end of 2019.

That deadline can be extended until 2030 if New Mexico demonstrates it isn’t responsible for delays.