Uncategorized

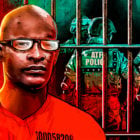

APD officer: 2016 federal sting operation focused on ‘volume,’ not ‘higher-level guys’

|

Tim Hotle, a 12-year veteran of the Albuquerque Police Department, in sworn testimony this week undercut federal authorities’ long-running narrative about a controversial 2016 law enforcement operation that snatched up disproportionate numbers of blacks and Hispanics. During his 45 minutes or so on the witness stand, Hotle told U.S. Senior District Judge James Parker that as a representative of APD he had helped plan the Albuquerque operation pushed by the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and the local U.S. Attorney’s Office. Authorities have repeatedly contended they arrested “the worst of the worst,” and a summary report of the operation stated that its goal was to infiltrate drug trafficking organizations “facilitated by” Mexican cartels. Most of the 103 people arrested, however, were picked up for their involvement in small-quantity drug sales; few had the types of violent criminal histories authorities said they were going after. Hotle’s testimony further undermined the federal government’s claims.

“We weren’t after the higher-level guys,” Hotle said from the stand during a court hearing involving one of the defendants arrested in the operation.