2015 was a brow-raiser for us here at NMID. And we’re not easily impressed.

2015 was a brow-raiser for us here at NMID. And we’re not easily impressed.

Republicans took control of the state House of Representatives for the first time in 60 years, shaking up the Roundhouse dynamics. In the final week of the 60-day session neither GOP House leaders nor the Democratically controlled Senate blinked in a game of chicken over capital outlay, legislation considered by many as important to the state’s economy. State lawmakers eventually passed the capital outlay bill, but only after returning to Santa Fe in June for a special session.

2015 was also the Year of Ignoble Resignations: Phil Griego, Dianna Duran (who later pleaded guilty to six criminal counts, including two felonies); Luis Valentino and Charles Trujillo.

There was an environmental catastrophe. In August millions of gallons of wastewater that had gushed into the Animas River, turning it orange, flowed into the San Juan River, a tributary of the Colorado River. As Laura Paskus wrote for NMID, Navajo Nation farmers who rely on the river’s water for crops closed their irrigation gates, even after the federal government assured people that the river’s levels of lead, arsenic and cadmium were safe again.

The state’s Public Regulation Commission, meanwhile, endorsed an energy plan for New Mexico’s largest utility. The Albuquerque-Rio Rancho area captured the spotlight for horrific violence, including shooting deaths of two police officers and a tragic “road rage” incident that killed a young child. And in November for the first time New Mexico led all states with the highest unemployment rate in the nation.

New Mexico In Depth’s Impact in 2015

As is clear, New Mexico burst with news this year. But for a young outfit with big aspirations, NMID chose a targeted approach to journalism, which we believe is key to making impact. With that in mind, here are some highlights from our year in reporting:

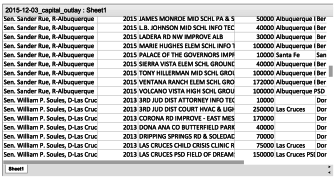

- A huge amount of money earmarked by state lawmakers since 2010 to pay for hundreds of capital outlay projects around the state remains unspent. It isn’t creating jobs or improving the quality of life in New Mexico communities.

New Mexico In Depth and its media partners discovered this after our data journalist Sandra Fish built a publicly searchable database of more than 2,500 projects valued at less than $1 million between 2010 and 2014. That threshold is important because staff at the Legislative Finance Committee, the Legislature’s budget arm, only alert lawmakers about projects valued at $1 million or more that aren’t progressing.

New Mexico In Depth and its media partners discovered this after our data journalist Sandra Fish built a publicly searchable database of more than 2,500 projects valued at less than $1 million between 2010 and 2014. That threshold is important because staff at the Legislative Finance Committee, the Legislature’s budget arm, only alert lawmakers about projects valued at $1 million or more that aren’t progressing.

Through our analysis we found that more than half of $337 million earmarked for local projects between 2010 and 2014 was unspent.

We discovered that once New Mexico authorizes money, there appeared to be no oversight to ensure timely reporting, which is one way to encourage more accurate tracking of spending. An additional weakness in New Mexico’s system for paying for projects is the lack of required planning at all governmental levels. In short, our reporting showcased how dysfunctional and inefficient New Mexico’s system is for tracking money meant for projects valued at hundreds of millions of dollars. As all of us know, New Mexico is one of the poorest states in the nation, where every dollar counts.

- State lawmakers insist they can keep secret how they spend state dollars on such projects but we disagree. We think it is public information. And when the public can’t see how legislators allocate their funds, New Mexicans aren’t able to gain insight into the role and influence of money — and lobbying — in politics and how responsive legislators are to their constituents. In the end, they’re kept from seeing how the Legislature really works.

Here’s how the highly political system of allocating public capital outlay dollars works:

Depending on how much money the state has each year, a figure is settled on to fund  capital projects throughout the state–highways, community centers, etc. Of that amount, individual lawmakers get a cut to spend on capital projects. For example, in the 2015 special session, legislators earmarked $84 million of the $294 million available. That means each senator in the 42-member state Senate received $1 million to propose funding for projects; and each representative in the 70-member state House of Representatives received $600,000.

capital projects throughout the state–highways, community centers, etc. Of that amount, individual lawmakers get a cut to spend on capital projects. For example, in the 2015 special session, legislators earmarked $84 million of the $294 million available. That means each senator in the 42-member state Senate received $1 million to propose funding for projects; and each representative in the 70-member state House of Representatives received $600,000.

While you can find each legislator’s annual “wish list” on the legislature’s website, how each House member spent that $600,000 — or $1 million in the case of a state senator — is secret. Legislative staff insist the information is exempt from New Mexico’s open records laws and can be released only with permission from each individual lawmaker.

NMID e-mailed all New Mexico legislators requesting they give permission to the legislative agency to release the information. So far, 12 of 111 lawmakers have given permission. No one said shaking the information loose was going to be easy, but we’re committed to getting these numbers. It’s in our job description as journalists. It’s information the public has a right to know. Plus it’s fun.

- New Mexico’s campaign finance reporting requirements are so lax that it’s impossible to know sometimes who’s giving money to candidates and elected officials — lobbyists or their employers.

Some lobbyists list their clients as contributing to candidates or elected officials when they are the source of the money. Other lobbyists don’t. The inconsistency makes it difficult to track where the money to candidates and elected officials is coming from. Candidates often list contributions from the businesses that donated, not the lobbyists who delivered the donations, according to a limited cross-check of candidates’ campaign finance reports.

Some lobbyists list their clients as contributing to candidates or elected officials when they are the source of the money. Other lobbyists don’t. The inconsistency makes it difficult to track where the money to candidates and elected officials is coming from. Candidates often list contributions from the businesses that donated, not the lobbyists who delivered the donations, according to a limited cross-check of candidates’ campaign finance reports.

Follow so far? No. Welcome to our world.

Last week, the Secretary of State’s office issued new guidelines for lobbyists that address some of those issues, clarifying how detailed lobbyists should be in reporting expenses and contributions. But there’s much more to be done.

Our discovery is yet another example of New Mexico’s inadequate campaign finance system. Every couple of years a scandal, sometimes more than one, erupts involving a top elected or appointed official, making us and others wonder if the secrecy around campaign finance is an accident or intentional.

New Mexico In Depth didn’t stop at examining the state’s rules and requirements for how lobbyists report campaign contributions, however. NMID wrote about how much they spent on elected officials between 2011 and 2014 and tracked their spending during the 2015 session, something we’ll do again during the 2016 session.

We also examined how lobbyists’ campaign contributions helped Republicans win the state House in 2014 for the first time in 60 years. And we reported the state’s universities, cities, counties and some public school systems spent more than $7 million in 2014 and 2015 to influence lawmakers in Santa Fe and Washington after examining dozens of lobbyists’ contracts.

- New Mexico lacks good data on the number of Native American youth who commit suicide each year, hampering intervention strategies.

Mark Holm © 2014 / For New Mexico In Depth

The moon rises over Thoreau as Hector Largo, left, takes a jump shot, while, Jacob James, center, and Damarco Pierce, right, await the rebound at the Thoreau Community Center basketball court in November 2014.

Two databases maintained by separate state agencies have differing totals for Native American youth suicides. That finding, discovered during the reporting for a series of stories published in May, suggested something else, too: both databases underestimate the true number of Native lives lost to suicide.

Without better data collection, no one can know the true extent of Native American youth suicide – and young Native people across New Mexico will continue to die.

Yet despite a growing awareness of the problem and repeated requests for help, the New Mexico Legislature has failed to dedicate sustainable funding to suicide prevention and intervention programs for Native American youth.

- New Mexico’s Changing Climate: A Special Project

Laura Paskus/New Mexico In Depth

In early May, the Rio Grande was suffering from a lack of snowmelt within its channel.

Many would say New Mexico is ground zero for climate change, given that we live in an arid region where water is our lifeblood. In the face of mega-drought and dying forests, many New Mexico communities struggle with how to adapt to a changing environment.

We think it’s important to understand how climate change is affecting New Mexico.

So, in mid-October, we launched a year-long project on just that. In two months, environmental reporter Laura Paskus has reported on changes already occurring in New Mexico, the impacts of warming on wildlife, how the state Legislature cut funding for scientists studying drought and economic vulnerabilities, what happened at the UN meetings in Paris, the difference between climate and weather (and what that means in New Mexico), and how communities of faith are responding to the Earth’s warming.

Stay tuned for much more in 2016.

Keep up the great work, guys (& gals).