Laura Paskus/New Mexico In Depth

Kerry Jones, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Albuquerque explains the difference between climate and weather. Laura Paskus/New Mexico In Depth

There are a few things that make Kerry Jones feel like his head is going to explode.

One is when people confuse “weather” with “climate.”

“Climate is what you expect,” says the meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Albuquerque. “Weather is what you get.”

Climate represents general conditions in a particular region — 30 years is the standard time period experts use for talking about it. Weather happens on a day-to-day basis, and is the fluctuating state of the atmosphere characterized by temperature, precipitation, wind, clouds, and other elements, he says.

Think about it another way, he says: Climate trains the boxer, while weather throws the punches.

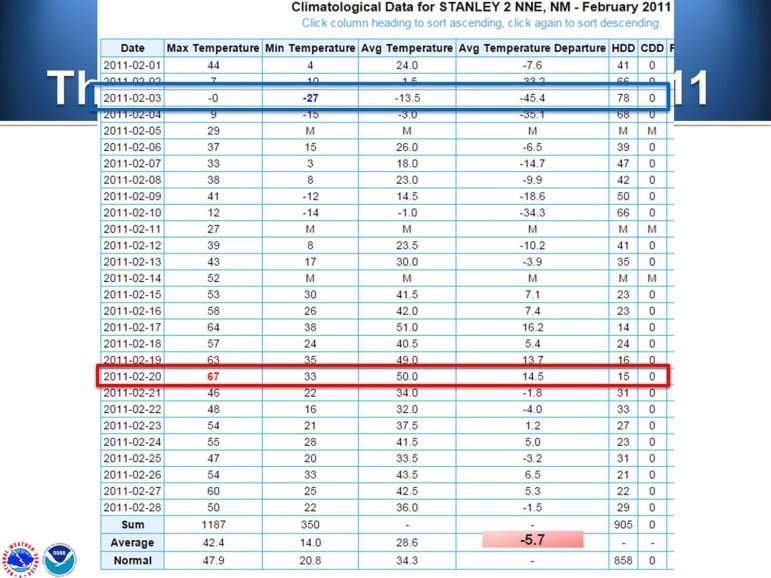

Talking to a room full of middle-school science teachers, Jones asks for a show of hands. Who remembers the cold snap in February 2011? In Stanley, New Mexico, for instance, it went from 44 degrees on February 1 to seven degrees the next day.

Hands fly up across the room.

That cold spell was so low and mean that it “overwhelmed” electricity plants and natural gas production facilities in Texas and New Mexico. People in northern New Mexico had their gas supplies cut when pipeline pressures dropped. And in southern New Mexico, companies implemented rolling blackouts to protect the overall systems. (Don’t remember all this yourself? The New Mexico Public Regulation Commission issued a report on it at the end of 2011.)

Then Jones asks who remembers the warm temperatures just a week later.

A couple of people raise up tentative paws.

By the ninth of February, it was up to 41 degrees; by February 20, the high temperature was 67 degrees in Stanley. And when it was all said and done, the month’s average maximum temperature was only about six degrees below normal.

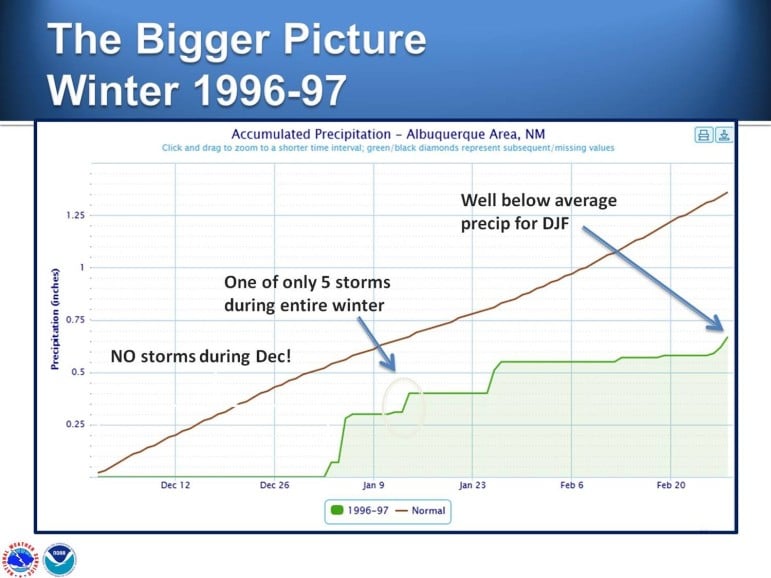

Jones brings up another example, showing a slide of huge snowdrifts along Frost Road in the East Mountains. “If you lived here then, everybody remembers the big snowstorms we had in 1997,” he says. That winter was actually below average when it came to snowfall. “But,” he says, “people remember the punches.”

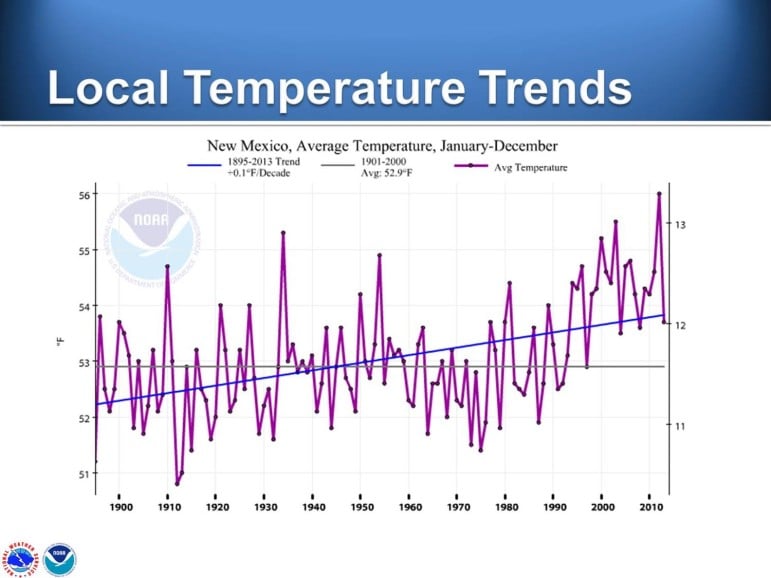

Thankfully, no one has to rely just on memory to understand what’s really happening. In New Mexico, some weather stations have been collecting records since the late nineteenth century. According to those records, average winter temperatures have risen steadily over time. In other words, the trends seen in those records show a changing climate.

It’s not warming up every single year and every single site, he explains, but you can see the trend itself when you look at the data.

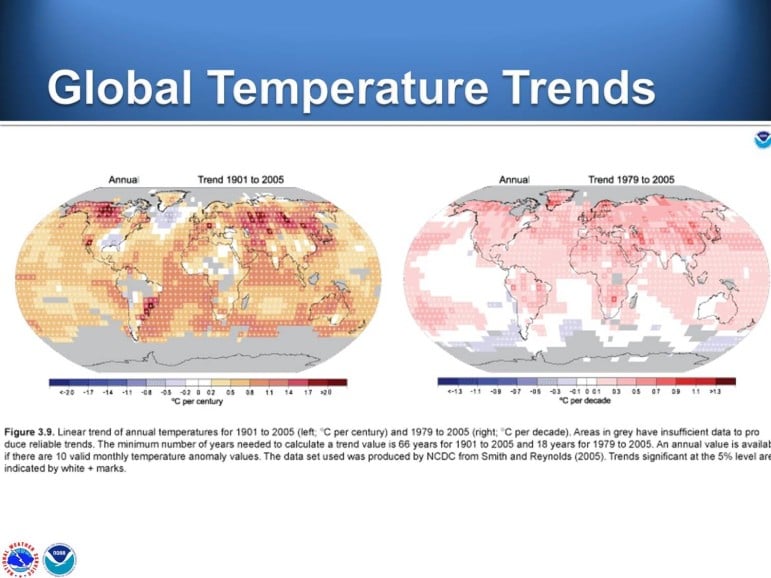

Worldwide, the warming trend is clear, too.

Memory is a tricky thing when it comes to climate, too, because people tend to think what they remember is the way things will always be.

Jones moved to New Mexico in 1994, at the very tail end of a wet period that lasted from 1984 through 1993. Many people, in fact, moved to New Mexico during that wet period. Between 1980 and 2006, the state’s population increased by 50 percent.

“We can see what’s happened since,” he says, pointing to higher temperatures and long-term dry periods. “But if you moved to New Mexico in that window, you became accustomed to certain things. And when they went away, you could find yourself asking a lot of questions.”

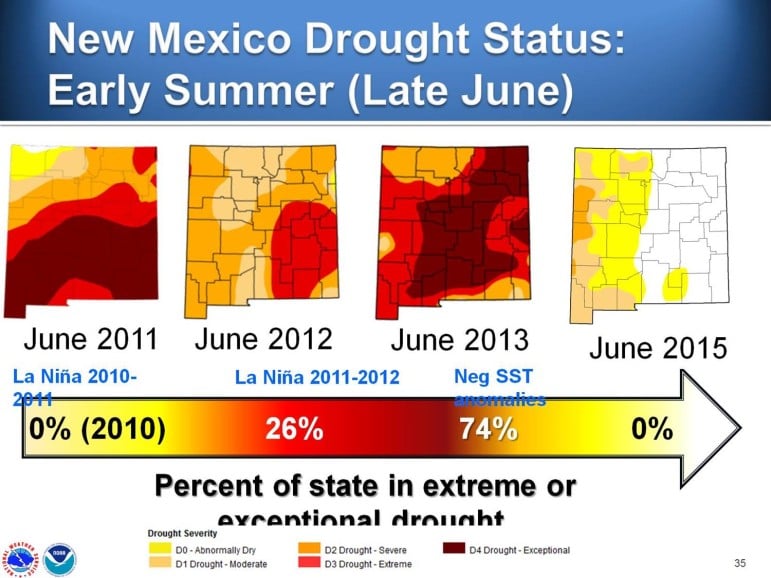

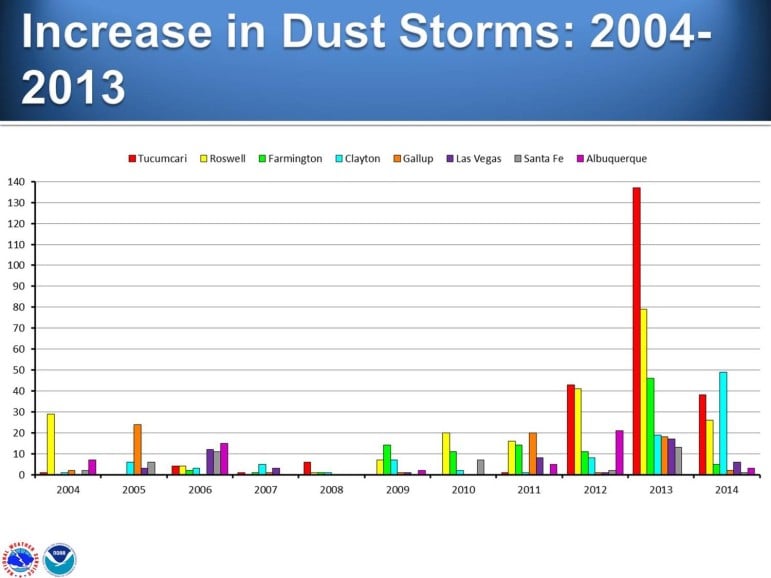

This year, the entire state of New Mexico moved out of “extreme” or “exceptional” drought, and also experienced a break from the increasing number of dust storms that had been occurring in recent years.

But that doesn’t mean there’s been a shift in the region’s climate. Rather, it’s due to some of the weather we’ve been having – mainly spring and summer rains that were higher than they have been in the past five years.

All of this brings us to the other thing that can drive Kerry crazy. Within the previous week, three different people had asked him, “When is El Niño coming?”

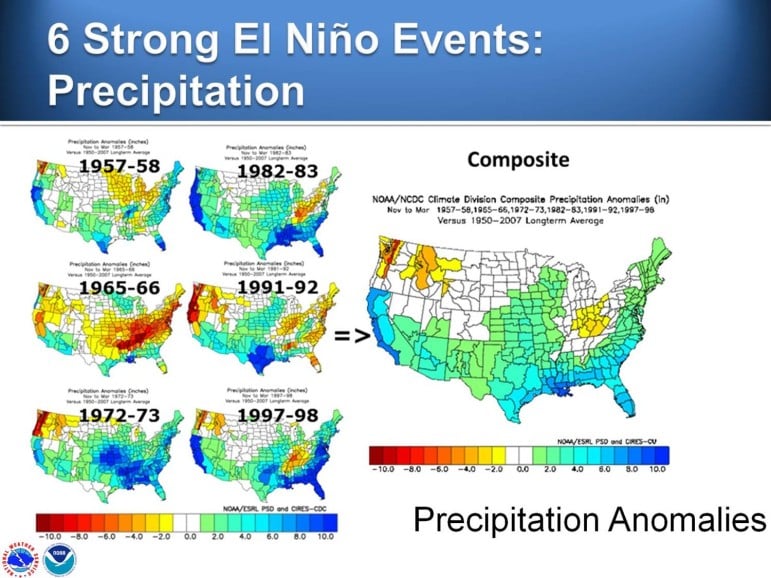

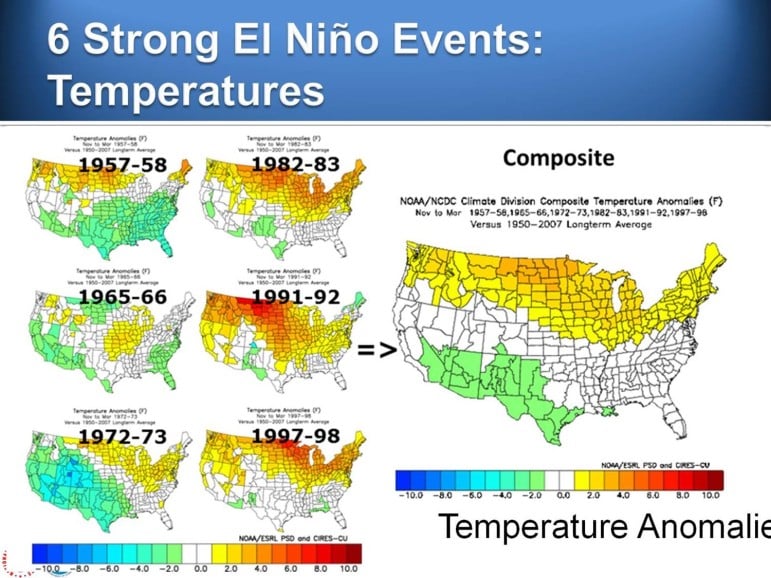

El Niño is related to changes in sea surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean—and for New Mexico, El Niño conditions can mean plentiful monsoons in the summer and increased snowfall in the winter.

El Niño conditions, says Kerry, have been in place since March. Now it’s a matter of waiting for active storm tracks. El Niño is a pattern that promotes precipitation, he explains, or “tilts the odds” toward a wet winter and spring. But it doesn’t guarantee anything.

And, he points out, every El Niño looks different. (And it affects regions in different ways. For a look at what might happen in different places, check out this fun read from NOAA’s Deke Arndt.)

Like water managers and farmers across the state, Kerry’s trying to remain hopeful. The monsoon storms this summer helped boost New Mexico’s situation in terms of precipitation and soil moisture.

But what the state really needs, he says, is a good winter snowpack.

Meanwhile, no matter what sort of weather the state experiences over the next few months, long-term warming trends will continue. And the Southwest’s climate will continue changing.