Welcome to State Budgeting 101.

Class starts when 112 state lawmakers convene in Santa Fe to approve a multi-billion dollar spending plan Gov. Susana Martinez can live with before the session ends Feb. 18.

That sounds challenging, but the Martinez administration and the Legislative Finance Committee, the Legislature’s budget arm, already have tilled the ground by drafting competing multi-billion-dollar spending plans. Those documents will act as guides for the New Mexico Legislature over the next 30 days as officials work toward a compromise.

New Mexico is a rarity. It is one of the few states in which the governor and the Legislature produce budget plans. The shared budget making helped New Mexico’s accountability grade in a November report from the Center for Public Integrity (CPI) (Disclosure: I was the reporter who compiled New Mexico’s data for CPI) . But the report also showed flaws. For example, our system gives an unusual amount of power to a small group of insiders.

New Mexicans don’t have access to enough information about the budget

New Mexico earned a letter grade of “C” in the CPI report for how accountable, transparent and responsive to the public our budget process is, mostly because the executive branch doesn’t make it easy for the public to ensure the state’s checkbook is balanced.

That’s a problem because lawmakers run the risk of building a budget based on the wrong numbers.

For example, the executive branch compiles what’s known as a Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) every year, but it has been consistently late—and there are no monthly or quarterly reports that indicate the state’s checkbook balances in the meantime. In fact, the independent auditor that examined New Mexico’s 2014 CAFR said it couldn’t determine whether it was accurate or not due to a lack of information. At least $100 million was unaccounted for.

As State Auditor Tim Keller told the Santa Fe Reporter : “You’ve got your checkbook and the amount you have in the bank. For the state of New Mexico, those don’t match.” A national budget watchdog group said the state had serious accountability problems in its budget reporting.

Technology increases citizen engagement

New Mexico does put a fair amount of budget information online, but making the data more accessible would help, transparency advocates say.

David Abbey, the director of the Legislative Finance Committee, says he’s proud of the committee’s website. “We have a raft of information in our documents explaining state finances,” he says. But Abbey admits, “These reports are, in some cases, 100 pages and it can be hard to find that information.”

That’s because the information is posted exclusively in PDF documents. That format makes it hard to dig through the pile looking for a specific issue and very hard to find trends or make comparisons.

Good-government groups have been pushing hard to make the data accessible so the public can take that raw information and make sense of it.

“Nationwide there’s a real trend in putting out budget information that’s in a downloadable, searchable and sortable format so people can play with it themselves and figure out where our money’s going or where it should be going,” says Susan Boe, executive director of the New Mexico Foundation for Open Government.

Some cities have taken advantage of 21st century technology to put their budget information online for citizens to interact with. Yes, the state budget is big and complicated, making such interactivity challenging, but at least one state has done the same thing, too

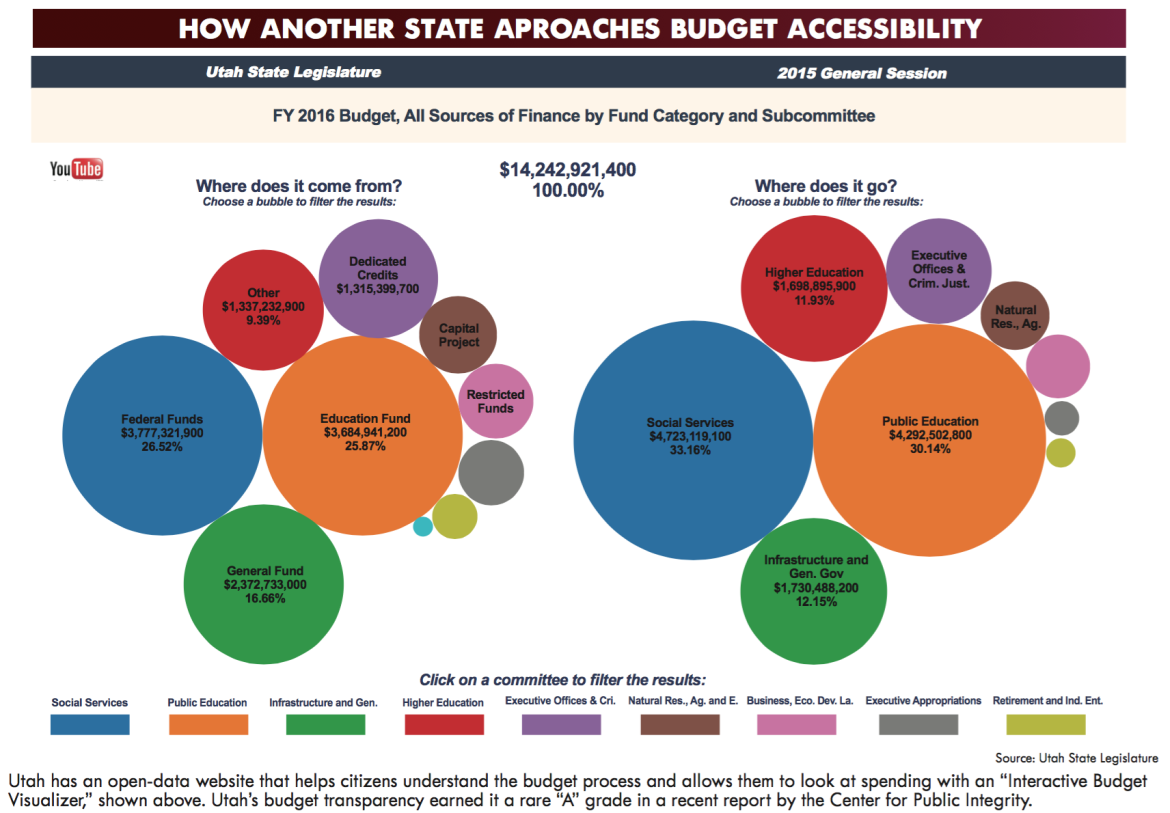

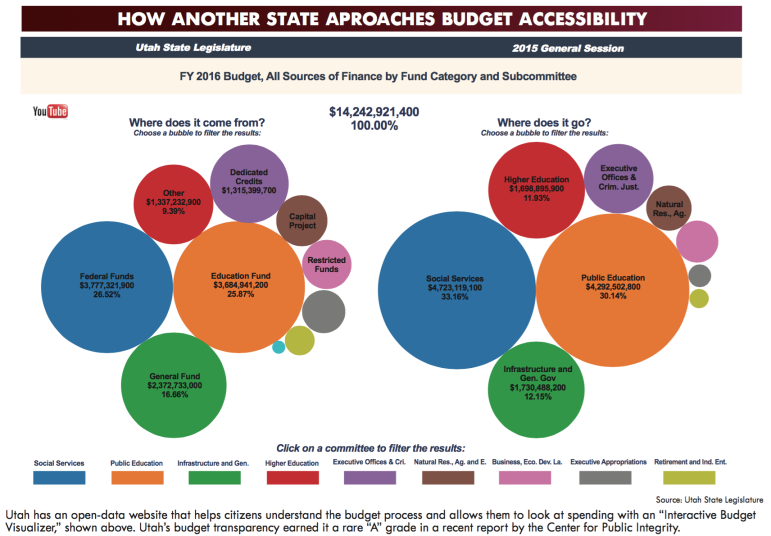

Utah has an open-data website that helps citizens understand the budget process and allows them to look at spending and revenue using an “Interactive Budget Visualizer.” Colored bubbles distinguish sources of revenue (federal funds, the general fund, the education fund) and where the money goes (public education, infrastructure, social services). Clicking on the “public education” bubble activates three other bubbles showing that money to pay for it comes mostly from the Education Fund, with a smaller amount of federal funds.

Utah’s budget transparency earned it a rare “A” grade in the CPI report.

In Colorado, where any new taxes must be approved by the voters, a nonpartisan civic-engagement group created an app called “A Balancing Act” that lets people build their own budget and share their priorities with state lawmakers. A companion app, “Taxpayer Receipt,” allows them to see what their taxes paid for last year.

“If Coloradoans are going to have the transportation, schools and healthcare that they want then there has to be a fairly high level of budget literacy among them,” says Chris Adams, president of Engaged Public, the group that created the apps. “So we thought it was very important for them to have a working knowledge of the budget.”

He says it only takes most people about ten minutes of looking at A Balancing Act’s colorful pie charts to form an opinion and type out some guidance to their elected officials.

Virtual public hearings could also help increase participation in the process, says Bruce Perlman. Perlman is a professor of public administration at University of New Mexico who worked in the state treasurer’s office. He also was a deputy chief of staff in Gov. Bill Richardson’s administration.

“Why are we doing all of this face-to-face? We should use the web more and allow people to phone in or Skype in” to give their input, Perlman says.

Budget as moral document

Compared to other states, New Mexico’s state lawmakers are remarkably accessible to the public. During the session they’re easy to find and approach in the capitol, before or after floor sessions and committee meetings. So it can be very easy to find your lawmaker and get a little face time.

The problem is that most folks don’t tune in to the budget process at all until it’s the topic of news coverage when the session starts, and by then the budget proposals have already been drafted, the thick lines have been drawn and only minor details tend to change. The budget bill starts in the House of Representatives. Lawmakers there hold hearings and eventually pass it, sending it to the state Senate, where the powerful Finance Committee has exerted great influence in recent years.

“The really important committees are the Legislative Finance Committee and the Legislative Education Study Committee… and they have meetings all year long but people don’t tend to go,” Perlman says. “That’s because people aren’t interested in the finance of the state generally,” he says. They’re interested in arts programming at their son’s school, a crumbling bridge they drive under every day or a tax break for putting in a solar energy system.

But people should care, says Ruth Hoffman, the executive director of Lutheran Advocacy Ministry, a group that advocates for reducing poverty, homelessness and hunger.

The way you choose to spend money says a lot about you. That’s true for a state, too, she says.

The state budget is a moral document that reflects us as a community, Hoffman says. “It reflects our values and what we prioritize, in terms of spending, but also of revenue, how we collect taxes and who we collect them from.”

Voters tend to choose candidates who share their values in broad terms. But after they’re in office, New Mexicans should be able to continue exerting influence on elected officials and the choices they make on the finer points.

“It’s a good thing that we’re one of the few states where both the executive and the legislative branches compose a budget because that means there are two ways to have input before the session begins,” Hoffman says

Experts easily navigate a system citizens call opaque

The route to influence is much more easily followed by those who are hired to do it. Lobbyists (some of whom are former lawmakers) have the expertise and relationships to focus their energy on the specific people and issues they’re paid to track.

Unlike Colorado and other states, New Mexico doesn’t require lobbyists or their employers to disclose compensation. Nor do lobbyists have to tell the public what legislation or issues they are following.

“Yes, some people have it a little easier because they have connections,” says Bill Allen, president of the Greater Las Cruces Chamber of Commerce, “but with a little sleuthing you can stay informed.”

“We always get an open door from Santa Fe,” he adds. “They make sure we have the chance to talk to them about what’s important down here in Southern New Mexico, and I’m appreciative of that.”