Image from www.CDC.gov.

In mid-March, dust storms hit southern New Mexico and the U.S.-Mexico border region. Fallow fields, construction sites, and dry patches of desert threw their sands into the wind, reducing highway visibility and causing people’s eyes to water and throats to constrict. This week, the National Weather Service issued a High Wind Warning—and officials worried about highway closures and fire risks.

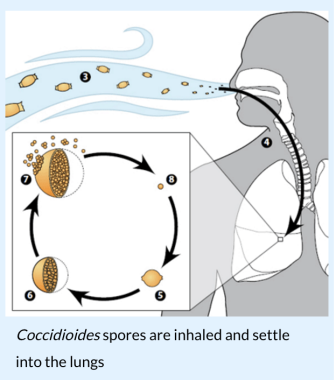

Dust storms can be deadly. In 2014, seven people died in a horrific multi-car accident on I-10 near Lordsburg when a dust storm whipped up by high wind came out of nowhere. But the hazards of dust storms aren’t reserved to car wrecks and fire hazards. Within the dust, there’s something else New Mexicans should know about: Coccidioides. That’s a fungus found in desert soils that can cause Valley Fever when it’s inhaled by people and animals.

Valley Fever offers a clear example of how public health and climate change intersect, says Dave DuBois, the state’s climatologist and a professor at New Mexico State University. As the region warms and soils dry out, dust storms could become increasingly common.

“We have disturbed soils from ranching decades ago, 50, 60, 100 years ago, and the soil hasn’t built back up—and in some places it may never, and we’re always going to have this issue,” he says. “When it’s very dry, even when we have just a couple of weeks of dryness, with the intense heat from sunlight in this area, the soil just dries out.”

New Mexico has experienced a dramatic rise in average temperatures—a trend that scientists say will continue. As the southwestern United States continues to warm, soil moisture will also decrease—on croplands and in forests, deserts, and grasslands. Based on one of the more conservative models, scientists have found that by the mid-21st century, summers in New Mexico will be much warmer than humans have ever experienced in the area.

New Mexico has experienced a dramatic rise in average temperatures—a trend that scientists say will continue. As the southwestern United States continues to warm, soil moisture will also decrease—on croplands and in forests, deserts, and grasslands. Based on one of the more conservative models, scientists have found that by the mid-21st century, summers in New Mexico will be much warmer than humans have ever experienced in the area.

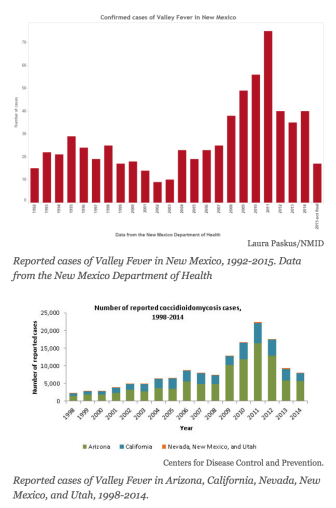

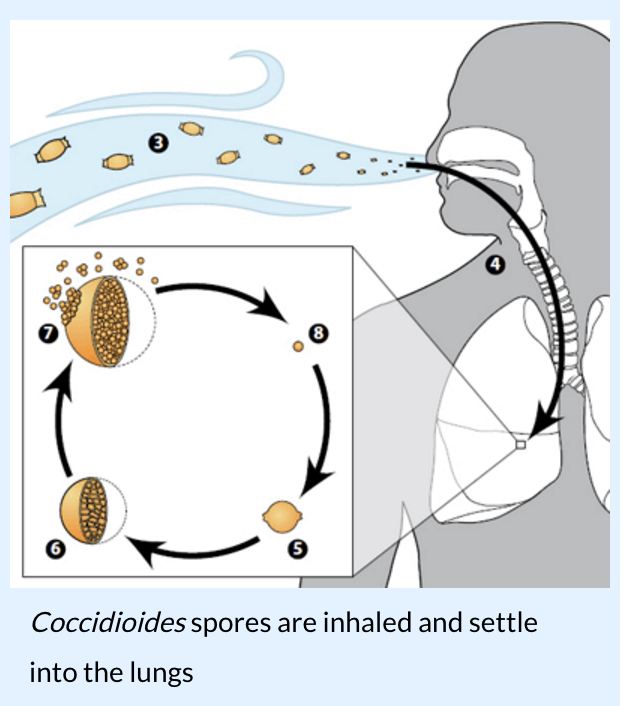

Meanwhile, Valley Fever cases vary year-by-year, depending on the severity of dust storms says DuBois: “When we have more rain, there’s less dust, so 2015 was a fairly quiet year.”

Most reported U.S. cases of Valley Fever occur in southern Arizona and California’s San Joaquin Valley. While there aren’t huge numbers of cases reported in New Mexico—fewer than 700 since the early 1990s—a few years ago a notable increase in cases alarmed Paul Dulin, now-former director of the Office of Border Health for the New Mexico Health Department.

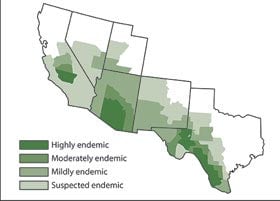

Dulin knew the fungus was present in southern New Mexico’s soils, thanks to a map of its extent from the 1950s. Around 2009, he started reaching out to public health colleagues in Arizona—who had experience with the disease—and Mexico, where he thought Valley Fever cases were also probably underreported.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In the 1950s, researchers mapped out where the fungus coccidioides was endemic in the soil.

Given the small, if rising, numbers reported in New Mexico and northern Mexico compared to Arizona and California, he hypothesized that the disease was being under-diagnosed by clinicians.

“It doesn’t make sense to stop at the border,” says Dulin, who retired in late 2013. People move back and forth across the border. And so does dust.

In particular, he wanted to raise awareness of the disease and improve its diagnosis. A 2010 survey Dulin’s office undertook found 69% of clinicians in southern New Mexico didn’t consider the fungal disease when diagnosing patients.

On average, says Dulin, a Valley Fever diagnosis can take six months. Not knowing what’s wrong, patients often go from doctor to doctor—“to hell and back,” says Dulin—and through multiple rounds of antibiotics, which don’t help the body’s ability to fight a fungal infection. Even anti-fungal treatment, says Dulin, “puts a damper on the disease, but doesn’t cure it.”

Valley Fever’s symptoms are similar to influenza and tuberculosis, though the fungus-borne disease is not spread through person-to-person contact.

And while nearly half the people infected with the spores never develop symptoms, severe infections occur in five to ten percent of cases, causing serious, long-term lung problems. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in some cases the infection even spreads into the nervous system, skin, bones or joints. And in 2014, a 60-year old Carlsbad man died from the infection.

Three years ago, the Office of Border Health released a documentary about three people in southern New Mexico diagnosed with the disease. It also sponsored public education campaigns and Valley Fever trainings for doctors in southern New Mexico.

Since Dulin’s retirement from the state, the department has prioritized different issues and initiatives. But he still hopes better data and disease tracking will lead to more reliable diagnosis—and that someday, drug companies will invest in a vaccine to help the body fight off infections from the fungus. “With the maelstrom of climate change, we don’t know what’s going to happen,” he says. “But we do know they’re missing a lot of cases.”

The DOH’s Dr. Chad Smelser says the department follows up on all the cocci reports they receive. But he’s not convinced the disease is becoming more common.

“One of the rules of infectious disease survey is: if you go looking for something, you will likely find it,” says Smelser, a medical epidemiologist with the department’s Infectious Disease Epidemiology Bureau. “And if you do education campaigns and you increase awareness, you will find more disease.”

People with weakened immune systems and those who work outside and come in regular contact with soils—such as construction workers and archaeologists—are most at risk of infection. And symptoms usually develop one to three weeks after inhaling the spores.

Anyone who thinks they might have Valley Fever should talk to their doctor, says Smelser. “If the physician thinks it’s appropriate, they can test them for the disease,” he says. “And we’re also open for people to call us if they have any questions.”

Excellent article! Thank you for helping to get the word out to the public to increase awareness. Early diagnosis is so important.