Recently, NMID reported on the risk of wildfire in the Sandia Mountains due to thousands of acres of trees killed by insects and disease:

Over the past five years, (Douglas fir tussock) moths and fir engraver beetles have hit the higher elevations, while the piñon ips beetle infested lower elevation trees.

All told, there are about 9,000 acres of dead conifers in the Sandias.

According to Andy Graves, the district’s entomologist, these native insects did what comes naturally in an overly dense forest that hasn’t seen fire in decades and is experiencing drought: They took advantage of stressed and weakened trees.

East Mountain Community Wildlife Protection Plan Update

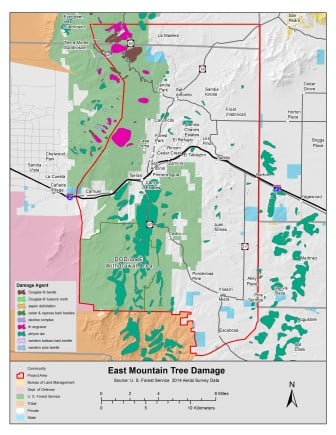

A map from the East Mountain Community Wildlife Protection Plan Update shows the extent of insect and disease damage in the Sandias.

After that story ran, a NMID reader was generous enough to send along a map that shows the extent of the insect and disease damage in the Sandias.

Published last year, the map is from the 2015 East Mountain Community Wildlife Protection Plan Update, which updates a 2006 community wildfire protection plan put together by a team of agency officials, fire chiefs, and community leaders concerning a 240-square mile area of the Sandia and Manzanita Mountains.

In the 2015 update, the authors describe the East Mountain communities as the “largest wildland-urban interface” in New Mexico, one that needs “plenty of work” to become “fire-adapted”:

The 2011 fire season in the Southwest challenged basic assumptions about fire spread and behavior. The Las Conchas fire burned an area larger than the Sandia Mountain Wilderness in less than 12 hours. In the same year, the Track Fire near Raton jumped six lanes of Interstate 25 within two hours of ignition. In 2012, 242 homes were lost in the Little Bear Fire near Ruidoso, NM. In light of these events and ongoing drought, East Mountain residents and emergency responders increasingly recognize the vulnerability of the largest wildland-urban interface in New Mexico. Although progress has been made on most of the action items identified in the original CWPP, there is still plenty of work ahead to make the East Mountains fire-adapted.

For more about wildland-urban interface communities in New Mexico, read our earlier story.

The 2015 report is a fascinating read, with lots of cool maps—including one on page 8 that shows the fire hazard risks within the planning area. The report also describes the methods used to reduce risk of fire in the East Mountains, including tree thinning and prescribed burns.