Dennis Roch and Bill Rehm are Republican lawmakers in the New Mexico state House. They represent the same number of people and receive equal dollar amounts for brick-and-mortar projects. In 2015, it was $600,000.

The similarities mostly end there.

The district Roch, a Logan school superintendent, represents stretches from Raton east to the Texas border and south to part of Portales. Funding requests from public schools, cities and seven counties can top $20 million a year.

“I’ve got 20-some municipalities with city halls and water systems and fire and police vehicles and trash trucks and sanitation equipment,” Roch said. He adds the counties in his district regularly ask for money for roads, water, assisted living and senior centers.

A retired police officer, Rehm’s district in northeast Albuquerque is a fraction of the size of his Republican colleague’s.

He has used money to pay to filter arsenic out of the Tierra Monte water system and to build the Paseo Del Norte intersection in Albuquerque. But he also has directed money to pay for little league fields — a luxury in a rural district like Roch’s.

“There’s so many needs and so little money to go around, all across the state,” Rehm said. “I could spend $200 million in my district tomorrow.”

Perhaps because of their experiences representing different districts, the two men disagree on whether New Mexico needs to reform how it pays for such projects — an issue state lawmakers may try to tackle when the 2016 legislative session begins today in Santa Fe. .

Outside groups have called the current system unusual, and one scholar has gone so far as to describe it as an “illustration about how not to do capital improvement planning.”

New Mexico provides ample evidence for such a view: Hundreds of millions of dollars sit idle for projects that were funded — in some cases, partially funded — but not shovel ready due, in part, to lack of state oversight.

Meanwhile, the system is shrouded in secrecy: neither the public nor the media can access what projects each lawmaker allocates money for year in, year out without first getting permission from the lawmakers themselves.

Meanwhile, the system is shrouded in secrecy: neither the public nor the media can access what projects each lawmaker allocates money for year in, year out without first getting permission from the lawmakers themselves.

Roch supports change and paying for projects the way New Mexico funds public school requests in which an appointed council ranks projects.

“Let’s focus our dollars on the highest needs first,” he said.

Rehm, however, worries how his district might be represented under such a program.

“If we went to a statewide type of system, someone else would make a decision on my district,” he said. “I should make the decision on how to spend money in my district, as long as it’s lawful, as long as it follows guidelines.”

The question of how to pay for projects across the state coincides with heightened scrutiny after the 2015 legislative session disintegrated in a dispute over not only what infrastructure projects to fund but how to pay for them.

At the heart of the dispute is the tradition of allowing lawmakers to allocate a significant portion of the available money to projects of their choosing. New Mexico is the only state in the nation that employs such a system.

Think New Mexico and its Executive Director Fred Nathan, which are leading a campaign to change the system, say it’s time to create an appointed commission that would rank state and local projects, with the Legislature and governor allowed to reject projects but not add new ones.

“Urgent projects are being passed over for projects that are not necessary and hundreds of millions of dollars is sitting idle on the sidelines because projects haven’t been properly vetted and are not shovel ready,” Nathan wrote in an email to New Mexico in Depth.

Unused capacity

A year ago, New Mexico In Depth began examining the current system and found that the processes the state uses to identify needs met many standards set forth in a report from the National Association of State Budget Officers. But the way state lawmakers divvy up money for projects is unusual.

While many priority projects identified by the executive and legislative branch are funded, a significant amount of capital outlay cash – $100 million in 2014 and $84 million in 2015 – is divided among individual lawmakers.

Following the meltdown in the final days of the 2015 legislative session, NMID created a searchable database of more than 2,800 projects funded from 2010 through 2014. Among the weaknesses NMID and media partners identified by analyzing the progress of the projects, or the lack of it, is that oversight to ensure the dollars are spent efficiently appears to be lacking after New Mexico authorizes money.

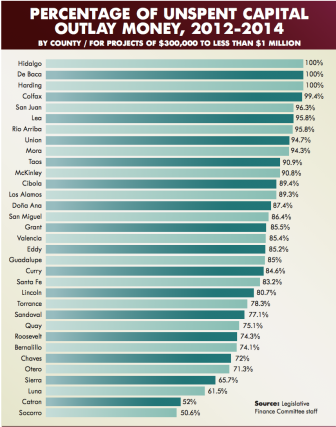

At least half the money allocated over five years has yet to be spent. Some projects will never get off the ground, others require more money after millions in investment.

A few months later, in late October, state lawmakers on the Legislative Finance Committee, which oversees budget planning including capital outlay, learned that $1 billion in the entire infrastructure bonding system remained unspent. That figure included funding designated for water projects, tribal infrastructure and other areas.

One-fourth of the unspent money came from lawmakers who had allocated money for local projects that weren’t shovel ready when proposed or weren’t making progress for other reasons.

Lawmakers who support the current system argue that dividing capital outlay money equally between the House and the Senate, then evenly among lawmakers in each body produces an equitable system. For example, in 2015 every member of the state House received $600,000 and every state senator got $1 million.

But an analysis of newly funded projects for the five years from 2010 to 2014 by New Mexico In Depth revealed a disparity in how much the state’s counties receive in per-person funding.

What’s next?

Since releasing a lengthy report on the history of the capital outlay system and its reform recommendations in October, Nathan and his staff have worked to build a coalition to support reform, both within the Legislature and outside interest groups.

Members of the influential Legislative Finance Committee have discussed the problems surrounding capital outlay funding at some of their fall meetings, including the amount of money that sits idle while projects that are funded are delayed, or never start.

“The question we often ask is, ‘Is it shovel ready?’, and they assure me it is,” LFC Chairman Sen. John Arthur Smith, D-Deming, said this fall. “Then you find out they haven’t bought the shovel yet.”

With so many projects idled, Smith said, “there’s tremendous pressure from the contractors to put more money into the pipeline.”

Nathan also noted the distrust between the executive branch and the Legislature on how to fund infrastructure that led to the meltdown in the final days of the 2015 regular session.

Think New Mexico hopes to bridge that mistrust.

“We thought we might be able to put forth a merit based reform bill that would generate thousands of more jobs and bring all sides together,” Nathan wrote.

While some lawmakers, such as Rehm, may not be on board with the reform efforts, Roch is.

“I think we’re long overdue in using a similar system (to public education) for capital outlay – all capital outlay.”