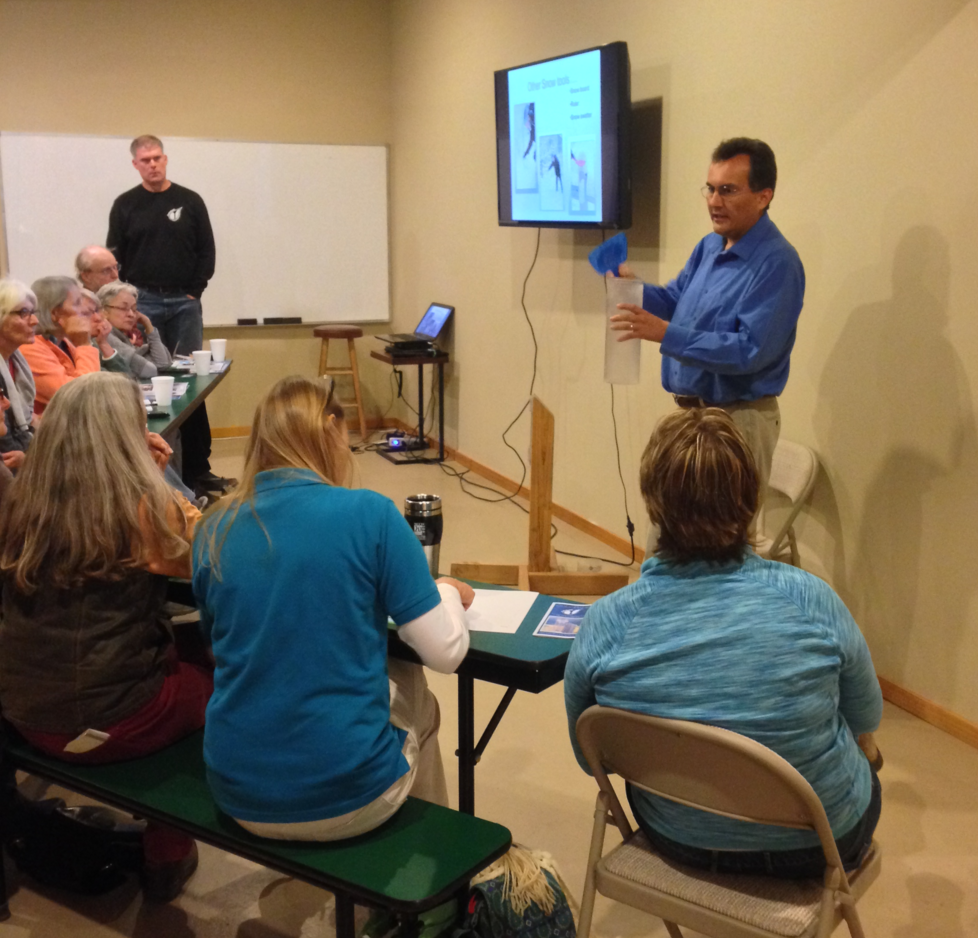

Photo courtesy of Christy Wall, Director of Science and Education, NM Wildlife Center.

Dr. David DuBois demonstrates how to use a snow swatter to measure snow to the CoCoRaHS Network. Photo courtesy of Christy Wall, Director of Science and Education, NM Wildlife Center.

When asked about the clearest signs of climate change in New Mexico, New Mexico State Climatologist Dave DuBois ticks off a long list.

“The growing season is continuously expanding. We’re having warmer morning temperatures, even outside the urban heat island. There’s a decline of snowpack in the mountains, a warming of the upper elevations,” he says. “With warming in the spring, we’re seeing allergy season expanding.”

DuBois pulls out an analogy to explain why we sometimes have cool or wet weather even while a warming trend began in New Mexico around 1970.

“I explain it like this: if somebody has a cancer, it’s a slowly moving disease,” DuBois says. “Some days, you might get the flu and feel that stronger than the long-term illness.” After the cold or flu passes, you may feel better—the stuffy nose or rattling cough has passed—but meanwhile, the cancer continues spreading.

It’s the same with climate change, he says. There might be cooler years here and there, but the overall trend is toward warming. Just like with a cancer diagnosis, he says it’s important to address climate change sooner rather than later.

“We’re seeing the impacts now,” DuBois says. “It’s not something that’s only going to happen in the future.”

The trends are more certain for temperature than precipitation, he says. But that warming affects water supplies. As the mountains continue warming, for example, more rain than snow will fall in the winter and spring.

“Less snowpack (and more rain) could mean we have more continuous river inputs, but we need that storage in the winter and melt-out in the spring because that’s the way our systems work,” DuBois explains. “We manage all our rivers and reservoirs to rely on that timing.”

Based out of New Mexico Climate Center at New Mexico State University (NMSU), DuBois collects and shares information on the state’s weather and climate with other scientists, government officials, and state and tribal employees. Even movie producers and insurance companies call him with questions about New Mexico’s climate.

DuBois participates in the state’s Drought Task Force and is the state coordinator for CoCoRaHS, the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network. In New Mexico, he says, more than 400 people contribute backyard rain gauge data to official measurements collected by the National Weather Service to create a more complete picture of the state’s weather and climate. He’s also an assistant professor in NMSU’s Plant and Environmental Science Department.

“The last few years have been a rollercoaster with different things going on,” says DuBois from his office in Las Cruces. “We know what happened in the past, so the big question is: can we really rely on the past to predict the future, or have things changed? There’s a lot of discussion about that.”

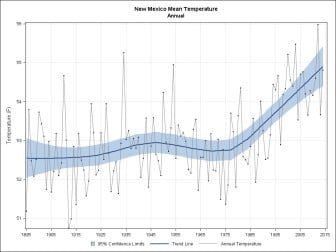

NWS, Abq

The National Weather Service in Albuquerque Tweeted out a graph showing the dramatic rise in statewide mean temperatures between the late nineteenth century and today.

Warming temperatures, for example, affect everything from when and where snows fall to how much snowmelt will make it into streams and rivers. In response to that warming trend, some scientists and water managers are looking for new ways to more accurately predict snowmelt and plan for how much water is available to farmers, cities, and ecosystems.

DuBois also does a lot of public outreach, talking with school children and attending community meetings. That work is especially important today, as climate change is affecting public health, the agricultural community, and the environment.

For example, as springs warm earlier—but may still pack a cold snap or hard freeze—farmers might be less sure of when to plant their crops. Meanwhile, more severe wildfires are burning in New Mexico’s forests. Afterwards, downstream communities may experience severe flooding; higher temperatures can affect which tree species can survive once a landscape has recovered from fire. When it comes to wildlife, some species are moving higher in elevation to seek the cooler habitat that suits them. Stream temperatures affect when fish spawn, and low water levels can lead to die-offs.

There are even more issues for people to consider today.

Last fall, for instance, DuBois met with staff at the Sustainability Office in Las Cruces to talk about extreme rainfall. Las Cruces had just experienced a costly hail storm. “We talked about: What if we had a six-plus inch rainfall in Las Cruces: what would that do? Would our infrastructure be able to handle it? What would the consequences be?” he says. “We need to be thinking about those kinds of questions.”

When meeting with a diversity of people—including those who are doubtful about the impacts of climate change—DuBois tries to explain what’s happening in a clear, calm way that doesn’t overwhelm people with scientific data.

But it is his moral responsibility, he says, to relay the information that scientists are learning—and agreeing upon.

“If I don’t tell people there is something coming their way, it bothers me,” he says. “Another case, on moral ground, is: how do we manage our land the best we can? If we start to let it decay now, what will be left for future generations—my kids, their kids? What will they have to deal with that we didn’t?”