As tribal members dig in their heels to prevent construction of an oil pipeline they say threatens their water supply and damages sites sacred to them, a growing police action in North Dakota over the weekend has landed many of them in jail.

Since the summer, thousands of Native Americans, including New Mexicans, have converged on North Dakota, heeding the call of the Standing Rock Sioux to protest against the pipeline construction.

Liz McKenzie, Diné, at the Hip-Hop for Water Event in ABQ during mid-September. Credit: Robert Salas/NMID

Liz McKenzie of the Diné Nation (Navajo Nation), for one, felt a sense of unity with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe when she visited North Dakota in September, she said.

The 2015 Gold King Mine Spill that contaminated the San Juan and Animas Rivers and affected agricultural communities in New Mexico and on the Navajo Nation made water contamination concerns raised by the Standing Rock Sioux more than a political call to action.

”It’s not even like we are standing in ‘solidarity’,” McKenzie said. “We are all in the same fight as a people.”

The Texas company building the pipeline, Energy Access Partners, has repeatedly touted the thousands of jobs the 1,172-mile pipeline would produce once completed.

However, Travis Miller, the political campaign coordinator for the Native American Voters Alliance, questioned the morality of emphasizing economic profits over “human well being.”

Like McKenzie, Miller traveled to North Dakota in September.

“We only have x amount of water and, if you destroy that water, then what are future generations going to have?” Miller said. “Every living organism in the world needs water to survive, we don’t need oil to survive.”

Miller also felt strongly about disturbance of sites held sacred by the Standing Rock Sioux. That tribe’s chairman, David Archambault II, lamented in a press release that “The ancient cairns and stone prayer rings there cannot be replaced. In one day, our sacred land has been turned into hollow ground.”

“They would never go through and knock down a cathedral because it was in the way of a road or a pipeline,” Miller said.

The Power of Social Media

Tony Webster/flickr

Dakota Access Pipeline protest at the Sacred Stone Camp near Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Credit: Tony Webster/flickr

The widespread support for the “No DAPL” movement among Native American tribes has led tribal officials to call the protests the largest gathering of Native Americans in more than a century, according to published reports.

The size of the protest, and the passion it has generated among protesters, has led some to question, Why now?

Professor Tiffany Lee, Associate Director of Native American Studies at The University of New Mexico, offered an answer.

Environmental degradation and pollution are common issues for tribes across the country, including in the Southwest United States. As an example, she cited a uranium mill spill that took place in Church Rock, N.M. in 1979.

Tiffany Lee, Ph.D. (Dine/Lakota) – Native American Studies Associate Director, University of New Mexico. Credit: Photo courtesy of UNM

A dam on the Navajo Nation near Church Rock, N.M. broke at an evaporation pond, releasing “94 million gallons of radioactive waste to the Puerco River, which flowed through nearby communities,” according to a May 2014 report from the U.S. General Accountability Office.

The spill happened three and a half months after Three Mile Island in which a nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania partially melted down and produced “small radioactive releases” that “had no detectable health effects on plant workers or the public,” according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Yet Three Mile Island generated much more news coverage than the spill in New Mexico.

“These sites, these open mines, obviously they toxify (the environment). It’s decades before they can be resolved,” Lee said. “They are still dealing with the effects on the communities there (Church Rock).”

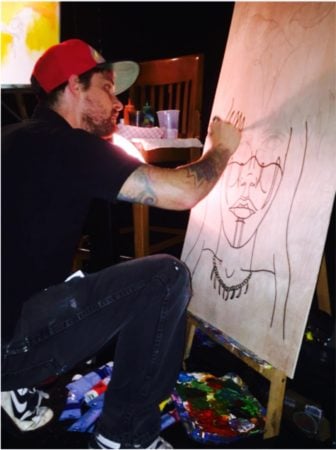

Skelley Greer creates artwork to be auctioned at “Hip-Hop for Water” event in Albuquerque. Credit: Robert Salas/NMID

With the protesters and company and law enforcement officials continuing to face off over the pipeline, it’s unclear how long the situation in North Dakota will last. However, signs are that protesters aren’t leaving anytime soon.

And local solidarity efforts like an Albuquerque fundraising event in September called Hip-Hop for Water will likely continue. That event raised almost $1,300 at Low Spirits, a local bar. Local artists showcased and auctioned their work, according to Christopher Mike-Bidtah of the Diné Nation, the event coordinator.

“They can use the money for whatever they need, such as winter supplies or food or, anything,” Bidtah said.

Robert Salas holds NMID’s 2016 fellowship for student journalists of color at the University of New Mexico.

I commend all of you on your efforts and whole-heartedly support your efforts especially when nobody at the top seems to be listening. Also, history can attest to the fact that the native american has never been given the respect and recognition that they deserve. I, also, have been writing to our present and past state governors and some of our representatives hoping they will take action that will put restriction on the pecan farmers in the southern part of the state that includes the Mesilla and Hatch valleys. They flood irrigate their properties like there is no tomorrow. As I walk around the area, I am reminded of the native american that looked over his country with tears in his eyes due to the way the land has been raped, littered and poisoned since the europeans first came to this continent. Not one of the them has even had the creourtesy of answering my distress letters. I keep telling them that I could live without having another pecan for the rest of my life, but we will not last more than a few days without water. Also, the way our aquifiers and water tables are continually going down, it will not be long before New Mexico becomes a barren desert. Buena suerte y que Dios los bendige, un amigo de el sur de nuevo mexico, Jesus M. Caro Jr.