In our society, money buys things. That includes at places like the Roundhouse in Santa Fe, where the textbook ideal is an informed citizenry empowered to ask elected officials educated questions about how decisions are made but where the reality often is more muddy.

In our society, money buys things. That includes at places like the Roundhouse in Santa Fe, where the textbook ideal is an informed citizenry empowered to ask elected officials educated questions about how decisions are made but where the reality often is more muddy.

What money buys in Santa Fe is a pressing question these days in New Mexico, where in the past three years, a former secretary of state has pleaded guilty to embezzlement and a former state senator has been convicted of bribery.

Over the last seven or eight years, due to public pressure following an earlier series of scandals, the New Mexico Legislature seemed to be opening the doors slightly on how decisions are made.

First, there was webcasting, allowing the public to watch lawmakers debate issues on the floor of the state House and Senate and, later, in legislative committee hearings. The state Sunshine Portal came, too, where people can search state contracts, al-though it is not searchable digitally. And state lawmakers finally over-came a deep-seated discomfort with an independent ethics commission and in 2017 passed a proposed constitutional amendment that voters will decide on this November.

So it was a bit of a surprise when during the 2016 legislative session state lawmakers reduced the amount of money spent by lobbyists and their employers that has to be publicly disclosed. Any expenditure under $100 no longer must be reported.

Lobbyists are versatile, knowledgeable actors in Santa Fe.

As a general rule, other people —individuals, corporations, governments, nonprofits — pay lobbyists to pass or kill legislation.

Depending on their specialty, lobbyists also might be asked to write complicated language for their employers to insert into existing bills. Or they might introduce their clients to powerful decision-makers. In Santa Fe, many lobbyists are former lawmakers, are relatives of former lawmakers or they once worked at legislative agencies, meaning often they are well-connected individuals.

Seeing more detail in lobbying expense reports, the thinking behind public disclosure goes, would allow the public to know more about who — whether people, corporations, nonprofits or governments — is trying to influence decisions, who has more access relative to others, and whether more scrutiny is deserved.

Some lawmakers, saying the reduced public disclosure was a mistake, pushed through a legislative fix that their colleagues passed last year.

Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces

Steinborn

“Let’s be honest, if a lobbyist is spending money, they’re not doing it out of the goodness of their hearts,” said Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces. “They’re doing it to influence you.”

But Gov. Susana Martinez vetoed it.

Now, going into 2018, it remains to be seen whether the governor and Legislature will let the reduced reporting requirements stay on the books.

Rolling back transparency

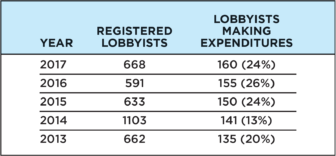

Hundreds of lobbyists register each year in New Mexico. Since 2013, the number has ranged from 591 on the low end in 2016, to 1,103 in 2014.

Only about a quarter of the registered lobbyists spend money each year. About half of that group — more than 60 lobbyists — have spent money every year since 2011, many of them representing multiple employers.

The flow of money takes several forms: There’s money for social events, big and small, that give lobbyists an opportunity to meet and schmooze with elected officials and other decision-makers.

Money also pays for gifts and other perks for elected officials. Businesses and other organizations, meanwhile, hire professional lobbyists or pay salaries of people who lead lobbying efforts. And lobbyists and their employers often contribute money to political campaigns.

Money also pays for gifts and other perks for elected officials. Businesses and other organizations, meanwhile, hire professional lobbyists or pay salaries of people who lead lobbying efforts. And lobbyists and their employers often contribute money to political campaigns.

The degree to which money influences legislators and other public officials is a long-debated subject. Entire research organizations, not to mention reporting projects, are dedicated to examining the subject, through research, analysis, and watchdogging the money and actions of public officials.

Sen. Daniel Ivey-Soto, D-Albuquerque, doesn’t believe legislators vote a particular way because of how lobbyists spend money. Rather, he believes lobbyists tend to support legislators with shared beliefs.

“It’s not that I will vote some way because someone gave me money, but instead, someone gives me money because I will vote some way,” Ivey-Soto said.

Regardless of the role of lobbyist spending and its influence, Ivey-Soto said people have the right to know where the money is going.

“The public has that interest and should be able to see that, both as the session’s going with regard to the large expenditures, as well as after the session, to be able to have an understanding of what took place,” Ivey-Soto said about lobbyist reporting requirements.

Ivey-Soto said the level of public disclosure by lobbyists should return to where it was prior to passage of legislation he sponsored two years ago.

In 2016, the state Legislature passed HB 105, legislation Ivey-So-to co-sponsored with Rep. James Smith, R-Sandia Park. The bill’s purpose was to make lobbyist re-ports more accessible to the public by requiring lobbyists to file online, allowing their reports to be more easily searched and analyzed.

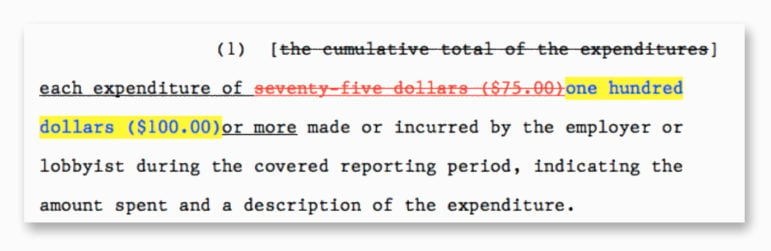

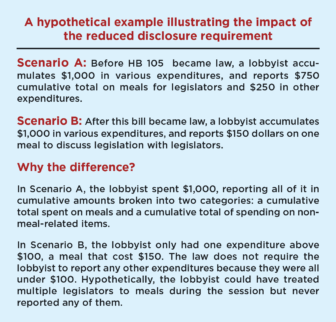

But it also eliminated a requirement that lobbyists report the cumulative amount of money they had spent during the reporting period. Instead, the bill inserted a rule that lobbyists had to report each separate expenditure of $75 or more. As the bill moved through committees, a House committee increased that amount from $75 to $100.

The bill as amended was then passed by the Legislature and signed into law by the governor.

The elimination of the reporting requirement for lobbyist expenditures under $100 was first noted publicly after the session concluded by New Mexico In Depth reporter Sandra Fish. What had been lauded as a transparency bill had, as it turned out, reduced required financial reporting.

The news surprised one of the bill sponsors.

“Oh my,” Ivey-Soto told Fish. “It was not our intent to get rid of cumulative reporting. That’s a vital in-dicator of what people are doing and what people are spending.”

The Fix

A general rule of thumb in the legislative process is that passing a bill takes time, sometimes many years, if ever, while killing a bill is easy. To pass a bill, both legislative chambers as well as the governor have to be on board.

In 2017, Ivey-Soto along with Sen. Joseph Candelaria, Steinborn, and Smith introduced SB 393 to insert cumulative reporting back into the Lobbyist Reporting Act. It was a simple bill, requiring lobbyist expenditures below $100 to be reported in the aggregate and expenditures of $100 or more to be detailed individually.

In 2017, Ivey-Soto along with Sen. Joseph Candelaria, Steinborn, and Smith introduced SB 393 to insert cumulative reporting back into the Lobbyist Reporting Act. It was a simple bill, requiring lobbyist expenditures below $100 to be reported in the aggregate and expenditures of $100 or more to be detailed individually.

The bill made it through the Legislature but the governor vetoed it. “The concern of the governor’s office was that [SB 393] was not grammatically correct and thus could be read in two different ways,” Ivey-Soto said in an interview.

When the May 2017 lobbyist reports were filed, New Mexico In Depth identified 20 lobbyists who reported no expenses between Jan. 15 through May 1 but who reported more than $23,000 in expenses the first four months of 2015, the previous 60-day legislative session (New Mexico’s annual legislative sessions alternate between 60-day and 30-day sessions).*

Another try in 2018

“I feel strongly about carrying this legislation because we had an un-intended consequence in the law,” Ivey-Soto said.

Ivey-Soto

Despite the 2017 veto, Ivey-Soto said Gov. Martinez liked the idea of closing the loophole, so he and his co-sponsors are working on language that will satisfy her concerns. Martinez did not respond to New Mexico In Depth’s question asking whether she would support a fix to the state’s lobbying disclosure law.

But getting a bill through the short 30-day session in 2018 could be an uphill battle, if the bill sees the light of day at all.

“It’s only going to be 30 days… a lot of things can go wrong and none of those have to do with oppositions to the bill,” Ivey-Soto said. “So I don’t know what … the odds of its passage would be.”

Known as a transparency and good government champion, Steinborn is hopeful his colleagues will support the fix to the 2016 law.

In addition to fixing the expenditure reporting issue, Steinborn has brought bills that would amend the Lobbyist Reporting Act to include more details about expenditures. Those changes would include on which legislator a lobbyist is spending money, and on what specific issues lobbyists are working. But those efforts haven’t made it out of legislative committees, much less to the desk of the governor.

“Sometimes with these big reform issues, you have to bite them off in chunks to get them past the Legislature,” he said. “There’s no time like the present to try and improve the state and the key is to be persistent and bring them up every session.”

*The state Legislature also added a new reporting due date in October for lobbyists and their employers, making year to year analysis difficult. New Mexico In Depth compared re-ported lobbyist expenditures in the first five months of 2015 and 2017, as comparable reporting periods over two 60-day sessions that sandwich the reporting requirement changes.

2018 legislative session: A look at critical issues before state lawmakers