Carlos Medrano of Mexico had to wait six days before guards let him call his family from the Otero County correctional facility where he spent two and a half months, incarcerated by a private prison company that holds undocumented immigrants for the federal government.

“They didn’t respect us,” Medrano told New Mexico state lawmakers through a translator in Santa Fe on Monday.

Roberto Gonzalez of Anthony, New Mexico, talked about the sadness he felt at not seeing his family for three months.

Gonzalez was arrested outside a courthouse where he had gone to conduct business that “he had a right to conduct” by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, he said through a translator.

Like Medrano, Gonzalez found himself locked up in one of two facilities in New Mexico that house undocumented immigrants for ICE.

“I have three kids, the oldest is in university,” he said.

It was nearly standing-room-only at Monday’s hearing focusing on conditions at two immigration detention facilities in New Mexico

For more than an hour, a line of immigrants told similarly harrowing tales of their time in lock up at the two detention facilities. The speakers included a Nicaraguan trans woman and a young woman named Leila from Somalia who spent a year and a half incarcerated.

Everyone who comes here for asylum should be treated in the proper way, she said, because they have good reason for seeking asylum.

“Who wants to leave their family back home? I left my baby of 2 years old back home,” she said. “Why would I leave my baby and come here, a foreign land, where I do not have family?”

Leila urged lawmakers to look into conditions in the detention centers, saying while it doesn’t have to be the best, “it should be human.”

State lawmakers scheduled Monday’s hearing to determine what, if any, authority the state of New Mexico might exert to learn more about the conditions in two immigrant detention facilities, the Otero County Processing Center in Chapparal and the Cibola County Detention Center in Milan, and to find out if they have jurisdiction to require changes.

The answers state lawmakers were looking for were in scarce supply Monday. In part because the acting director of ICE who had been invited did not show up. Nor did representatives of CoreCivic and Management and Training Corp., the two private prison companies that operate the facilities — a situation that piqued some state lawmakers who publicly expressed their displeasure.

Democratic Rep. Javier Martinez described the unresponsiveness as “disrespectful,” adding, “It’s disappointing that a body like ours would be so grossly ignored.”

Ann Morse of the National Conference of State Legislatures and Adriel Orozco of the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center testified before a committee of the New Mexico Legislature on Monday.

Ann Morse, director of he National Conference of State Legislatures’ Immigrant Policy Project, told lawmakers that the recent trend among states is to lower the number of people in their prisons. “These facilities are increasingly being used to house immigrants,” she said.

Morse was unable to answer lawmakers’ questions about what jurisdiction New Mexico might have to get answers to their questions about conditions in the facilities but promised to research them and get back to the New Mexico Legislature.

Rep. Jim Dines, one of the few Republican lawmakers to show up for Monday’s hearing, encouraged his colleagues to think about using contracts the private prison operators have signed with public governments — in this case, the two counties where they are operating — to access public records related to the facilities.

The conditions in the two facilities and the treatment of undocumented immigrants housed there have become a high-profile issue as the Trump administration has cracked down on immigrants across the nation. Unlike previous administrations, people who have no criminal records and pose no threat to public safety are now being targeted by ICE, a change that has provoked widespread protests and criticism.

The hearing also follows the high-profile death in May of Roxsana Hernandez, a 33-year-old trans woman who died of HIV-related complications soon after her transfer to the Cibola county facility.

“Equating immigrants with street criminals is unconscionable. But it’s good politics,” Albuquerque Democrat Antonio Maestas said.

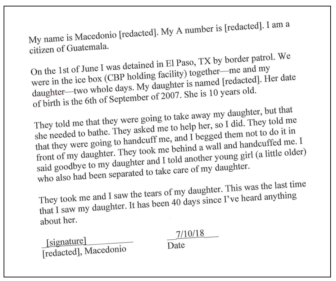

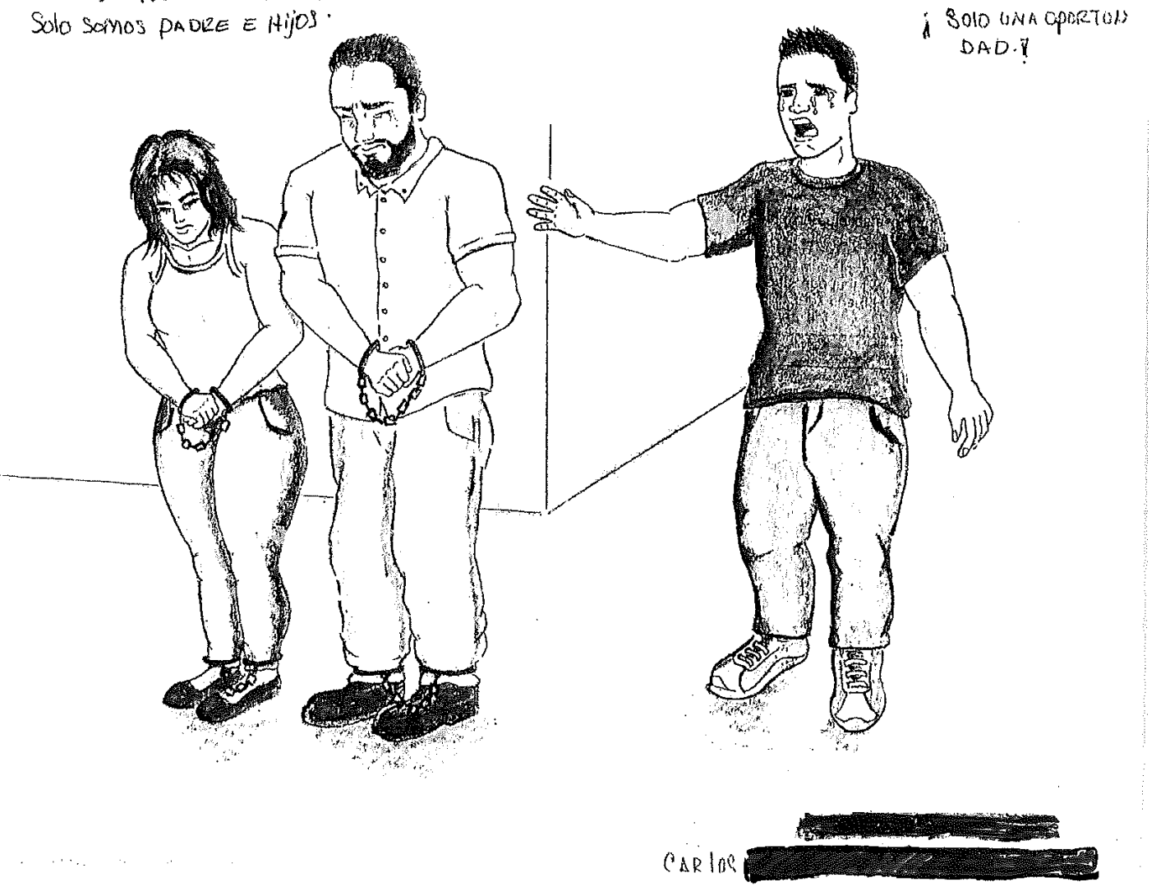

A letter from a detained immigrant included in a packet submitted to a New Mexico Courts, Corrections, and Justice Committee hearing on July 16, 2018. The letters were translated by Adriel Orozco, attorney with the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center.

Among Monday’s speakers was Adriel Orozco. An attorney with the New Mexico Immigration Law Center, Orozco has visited both facilities and said about 70 fathers who had been separated from their families were currently locked up in the Cibola County facility. Along with his testimony he submitted a packet of letters from those fathers.

A troubling issue Orozco focused on is lack of legal representation for immigrants, who have a much greater chance of prevailing in court if they have an attorney. According to Orozco only about 14 percent of detained immigrants across the nation have legal representation.

Immigrants from the African countries Congo and Guinea told lawmakers Monday about the conditions and treatment at two immigration detention facilities in New Mexico

Following the money

While New Mexico is in the top tier of states that rely on private prison contractors — nearly half of New Mexico’s prisons are privately operated — the industry doesn’t throw money around like some other industries when it comes to donating to campaigns. CoreCivic, formerly Corrections Corporation of America, and The Geo Group are the primary givers, a review by NMID found. MTC gives only nominally.

For the 2018 election cycle to date, CoreCivic and Geo have given $28,800 to state level candidates. While the giving is relatively small compared to other industries, it’s higher than in years past, with months to go before the end of the election cycle.

One of the lawmakers asking questions at Monday’s hearing — Rep. Eliseo Alcon, D-Milan — is one of two in the Legislature to have received campaign contributions from the private prison operators in each of the five election cycles from 2010 through 2018. The other is Gallup Democratic Rep. Patricia Lundstrom, who chairs the Legislature’s powerful House budget committee.

Alcon, who represents Cibola County, spoke Monday about the importance of the facility to the economy of his “little community.”

“We have to find a way to keep people employed,” he said.

In addition to giving about $121,000 directly to candidates from 2010 on, The Geo Group and CoreCivic have contributed $104,250 to political action committees over the same period. Of that, $80,200 went to Advance New Mexico Now, a group closely aligned with Gov. Susana Martinez. Another $10,000, in 2016, went to a conservative New Mexico PAC, NM Prosperity. But so far in the 2018 election cycle, just one $500 contribution has been reported by CoreCivic to New Mexico Senate Democrats.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect a new giving total for the private prison industry in the 2018 election cycle.

I respect Rep. Alcon, and still I disagree with the thought that for-profit prisons should ever be considered to be a viable way to bring income to rural communities. The “prison industry” is venal and immoral. It is wrong to make a a profit from human misery. Prisons, like every piece of our systems of justice, must be under the direct, immediate control of public agencies, be completely open to public examination, and must never be operated for profit.