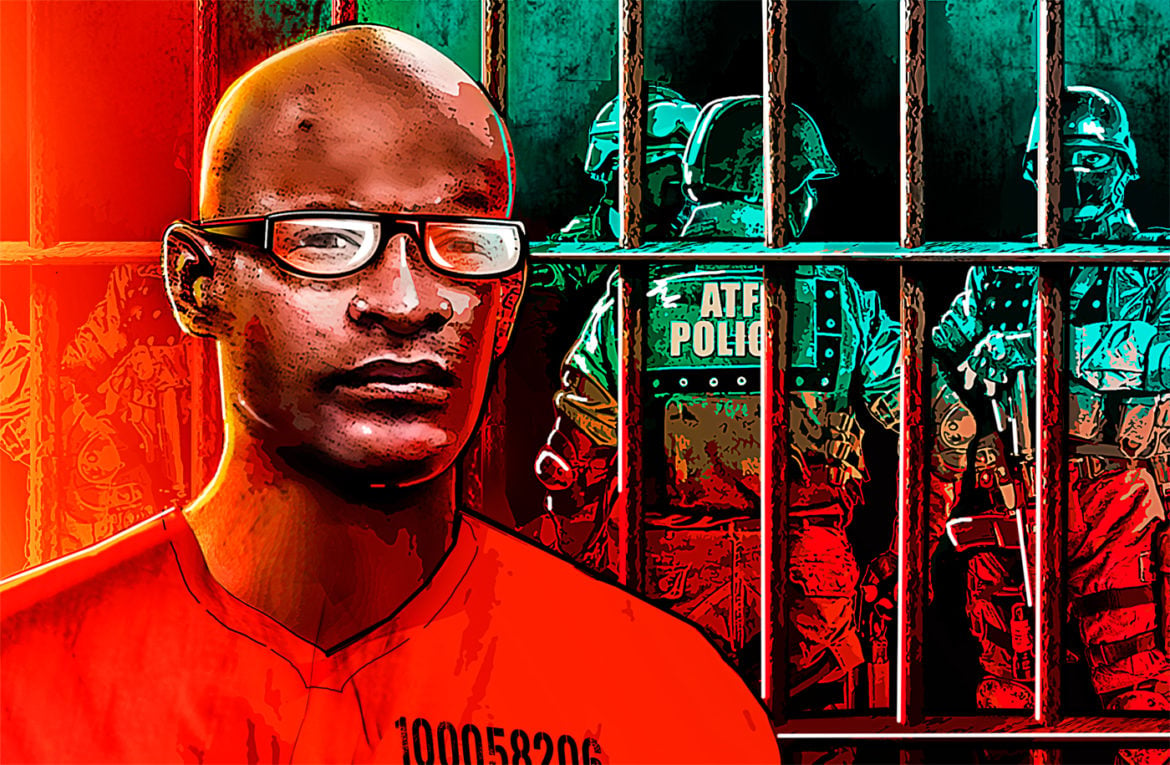

Yusef Casanova has sat in a prison cell for 27 months — charged with federal drug and gun offenses after his arrest in a 2016 undercover sting operation in Albuquerque.

On Dec. 20, his attorney will drive him to the Four Winds Recovery Center, a drug rehabilitation facility, just outside Farmington.

It’s an unusual turn of events: A federal judge ordered the release of Casanova, who is facing decades in federal prison if he’s convicted.

Casanova was swept up in an undercover operation that arrested a highly disproportionate percentage of black people. Casanova, like others, is alleging he was racially profiled by the federal bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), which designed and oversaw the operation.

While the federal government touted the operation as arresting the worst of the worst, many were low-level drug offenders, such as Casanova who at the time of his arrest was living in his car.

NMID has followed Casanova’s case since early last year.

With his placement in the rehab center, Casanova, 45, won’t be a free man in the eyes of the law, but he will be free from the privately operated New Mexico prisons where he’s been confined since ATF agents arrested him in August 2016. And he’ll get help for what he has described as a decades long struggle with drug addiction.

At least temporarily.

The move comes after U.S. Senior District Judge James Parker granted a request from Casanova’s federal public defender, Brian Pori, to release him until Parker rules on whether to dismiss charges in the case. Casanova is charged with distributing 5 or more grams of meth, being a felon in possession of a firearm and possession of an unlicensed firearm.

Pori has been litigating a claim for nearly two years that Casanova was targeted in the four-month operation and arrested because he is black. The hearing on the motion to dismiss charges against Casanova is scheduled for early next year.

Court clerk’s notes from the hearing at which Parker ordered Casanova’s release to the treatment center indicate that he can remain there — under “home confinement” and fitted with an electronic, location-monitoring ankle bracelet — until the hearing. It is not clear whether he will be allowed to remain at Four Winds if he loses his motion to dismiss and the case proceeds to trial.

New Mexico In Depth’s ongoing series about the ATF operation has spanned a year and a half and has raised questions about racial profiling and ATF’s tactics — including its use of confidential informants. It also has highlighted similarities between previous operations run by the same ATF agents in other cities, where a disproportionate share of black people were also arrested.

In Casanova’s case, agents did not pursue the white man who gave the meth to Casanova and moments later sold it to an undercover agent.

At the time, Casanova was living in his car and battling a debilitating meth habit.

“I’m being made out to be this big drug dealer,” Casanova told NMID in an interview last year at the Torrance County Detention Center. “I feel like they employed me to commit a crime, knowing I was homeless and had a habit.”

While federal law enforcement officials have said they arrested the “worst of the worst.” NMID’s review of court records found that the vast majority of the 103 people arrested — 28 of whom were black — did not have the kinds of lengthy, violent criminal records agents have said they used when deciding who to target. In nearly every case, the quantities of drugs and guns people sold to undercover agents were relatively small by federal standards.

Casanova isn’t the first of the ATF sting defendants to be sent to a place that focuses on drug treatment as opposed to a federal prison by way of a judge’s order.

In January, U.S. District Judge William P. “Chip” Johnson accepted a plea agreement in the government’s case against Jennifer Padilla, a now-40-year-old Albuquerque mother of five, that allowed her to be sent to a halfway house in lieu of further incarceration.

Padilla spent nearly a year and a half behind bars after her arrest in the ATF sting. She was facing 10 to 13 years in federal prison if convicted on charges that she arranged two meth deals.

But Johnson’s order in her case came after allegations she made in court motions that an ATF informant targeted her while she lived in a halfway house and enticed her into a romantic relationship, which he exploited to lure her into using drugs again and setting up the drug deals.