Yesterday as I watched Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham’s news conference about Covid-19 via livestream I flashed back to 2003 when Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) was sweeping the globe. The moment strengthened an urge I’ve had the past few days to think about the lessons I learned more than a decade and a half ago.

At the time of the SARS outbreak, I was working in Hartford, Conn. and already pondering how diseases spread. I’d spent late 2001 and early 2002 covering anthrax after a 94-year-old woman living 10 or so miles from our family was one of five Americans to succumb to the disease.

I mention anthrax only because it introduced me to epidemiology, a branch of medical science that tracks infectious diseases. I don’t want to overstate the case. The anthrax attacks of 2001 were the product of bioterrorism. SARS, meanwhile, was a virus in the same family as Covid-19 new to human beings that raged through countries, similar to its cousin virus.

But it was anthrax where I began to understand how epidemiologists — think of them as disease detectives — track the spread of contagions like SARS and this year’s covid-19.

Lesson No. 1: How infectious diseases move through human populations

If you watched the governor’s press conference yesterday you might remember one of the speakers saying the phrase “contact tracing.”

It’s the timely, labor-intensive process by which epidemiologists track how a disease moves through a human population. Hearing that definitely took me back to Thanksgiving week 2001 when experts couldn’t understand how a 94-year-old woman named Ottilie Lundgren in small-town Oxford, Conn. had come into contact with anthrax. She didn’t live in any of the targeted metropolitan areas — New York City, or Washington, D.C., or Boca Raton, Fla. near Miami — where other victims and fatalities of the bioterrorist attacks lived.

As soon as anthrax was confirmed as the culprit, a team of epidemiologists flew into Connecticut from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They began the arduous operation of documenting everyone Ottilie Lundgren had come into contact with, including one of her friends — a nurse as I recall — who’d begun a diary after noting the steady progression of her elderly friend’s worsening health. The CDC team used that diary and many, many interviews to try to crack the mystery of Lundgren’s infection. Ultimately, experts theorized the 94 year old had contracted anthrax from junk mail that had passed through the same Trenton, N.J., postal center that handled anthrax-tainted letters sent to U.S. senators Tom Daschle, D-S.D., and Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.

So by the time SARS hit, I’d been thinking a lot about how viruses and bacteria — anthrax is bacterial in contrast to SARS and covid-19, which are viruses — spread. It’s through everyday actions we don’t think much about.

Lesson No. 2: Your actions affect others

Similar to SARS, the most common ways of transferring Covid-19 from person to person are through close contact — within about six feet — and respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

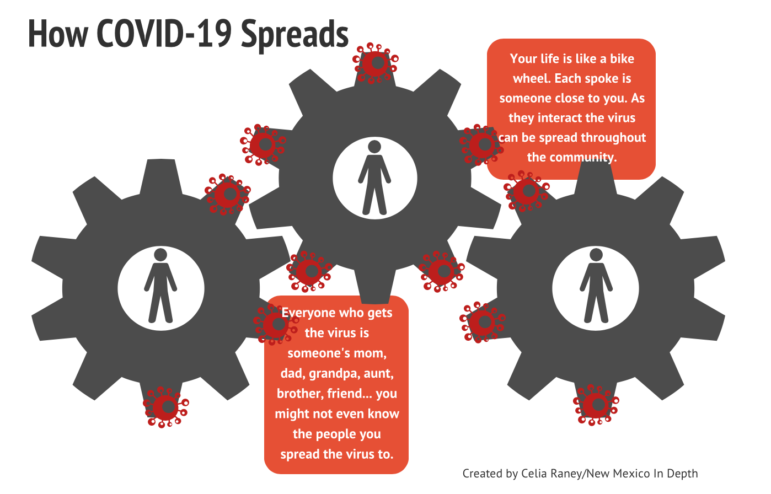

As this point, it might be helpful to think of your life as a bike wheel. You’re the hub from which the spokes — your family, friends, work colleagues and acquaintances — radiate. We each have many connections, which is how infectious diseases spread so quickly. One person has the potential to infect many others, including possibly individuals in high-risk groups such as the elderly, people with chronic health conditions and compromised immune systems.

Lesson No. 3: Infectious diseases don’t hit everyone equally

Some of us are more vulnerable than others. In the case of Ottilie Lundgren, I remember officials theorizing she might have survived anthrax if she had been younger. Of the more than 40 people exposed to anthrax in 2001, 22 got sick and 5 died, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

With Covid-19, as with anthrax and SARS, older adults and people with serious chronic medical conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and lung disease are the most vulnerable, the federal agency says.

Lesson No. 4: Do not panic.

I’ll admit this was extraordinarily difficult during the 2001 anthrax attacks. But over time I learned to lean on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the state Department of Health for factual, helpful updates and that lesson helped me make sense of the later SARS outbreak.

Relying on these sources, I noticed most people weren’t dying from SARS. However, the elderly and people with underlying chronic health conditions were much more vulnerable, as they are with this new coronavirus.

Looking back, SARS didn’t spread as widely, but its fatality rate — 10% (774 reported deaths out of 8,000 cases) — was much higher than the preliminary rate of 3% we see from the current virus. Covid-19, which has killed more than 4,200 globally, appears to be much more lethal than the seasonal flu and, it bears repeating, most dangerous to older people or those with chronic health conditions.

In New Mexico, we have five presumptive cases of Covid-19 (the CDC is confirming those results), the New Mexico Health Department says.

So far, most of the cases involve people who likely were infected while traveling rather than contracting Covid-19 from spread within their local community, which is good. I say most, not all, because state officials are still investigating a possible travel link with the fifth infected person.

Those folks identified as presumptively infected are a Socorro County husband and wife, both in their 60s, with known recent international travel to Egypt. Both are at home in isolation. The third case involves a woman in her 70s in Bernalillo County with known recent travel to the New York City area. She is also isolated at home. The fourth is a woman in her 60s in Santa Fe County who also traveled to the New York City area. The fifth case is a Bernalillo County woman in her 40s, according to the governor’s office. As I said above, the Department of Health is investigating a possible travel link. She is at home in isolation.

Keeping the virus contained is why the governor and state officials keep hammering to take precautions. On Thursday, the state’s health secretary issued an order prohibiting gatherings of more than 100 people across the state. The order exempts airports, other mass transit, shopping malls, shelters, retail and grocery stores, offices and businesses, courthouses, all educational institutions, child-care centers, health care facilities and other congregate care facilities and places of worship. Here’s a fact sheet.

As in other states, New Mexico is taking these actions, officials say, to slow the spread so as not to overwhelm the state’s health care system. A New York Times story published earlier this week contains a helpful graphic that shows what an unchecked contagion moving through the population looks like versus a contagion that is contained.

What are the most important precautionary measures?

Clean your hands often

Avoid close contact

Stay home if you’re sick

Cover sneezes and coughs

Wear a face mask if you are sick

Clean and disinfect (The CDC even has a complete guide to this)

Lesson 5: Seek good, accurate information

As I think back on 2001 to 2003, and all the memories Covid-19 has dredged up, I recognize how much has changed. SARS happened prior to the advent of social media. The internet, for most people, was still in its infancy. These days, there are myriad ways to spread information — even false, and dangerous information, particularly as fear grips the population.

During public health crises, it’s often difficult to separate good info from bad so it helps to know where to go. The CDC and your state’s health department have experts who’ve spent their lives thinking about infectious diseases and the movement of contagions through human populations.

So, with that in mind, here’s the CDC’s page on the coronavirus/covid 19, which it regularly updates. It has links to pages that tell you what you need to know, how the virus is thought to spread, who’s at greatest risk and precautions you should take. (Here’s the CDC’s latest summary of testing being done in the United States, too.) Here’s New Mexico Department of Health’s page that tallies the state’s confirmed cases and the hotline number of 855-600-3453.

It’s important to remember what this coronavirus is. It is not the annual flu. Humans have been successfully fighting that for decades. Nor is it the Spanish flu of 1918 that killed tens of millions. Beware of information making that comparison. It’ll only terrify you for no good reason. Here’s a good New York Times piece with helpful context to help guard against being taken in by such fear mongering.

Remember too that viral outbreaks are not static; and neither is the scientific method. Because this coronavirus is new, the more scientists, epidemiologists and researchers study it the better they’ll know how it behaves. So it’s important to understand experts will update what they know as they know it. That means the scientific method is working.

Hope all this helps.