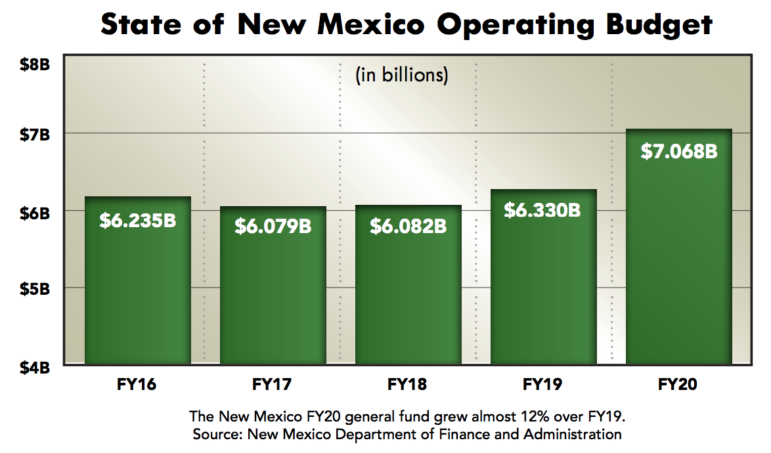

We pick up where our story left off last year. As in 2019, we find New Mexico’s fortunes glittering in a 21st-century version of a gold rush in the oil-rich southeast as state lawmakers prepare for the 2020 30-day session.

Policy makers will have about $800 million more in revenue than this year’s state budget to work with when crafting the state’s spending plan for the fiscal year that starts July 1.

In an election year like 2020, it’s easier to partition a surplus than to cut programs and services, as state leaders discovered a few years ago in 2016 after a freefall in tax revenue forced painful choices.

“We’re lucky to have the kind of revenues that are coming into the state,” Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham told an audience last month at an Albuquerque town hall.

There’s always a “but,” however, and Lujan Grisham didn’t disappoint. After acknowledging New Mexico’s gilded economic forecast, she recited a backlog of needs..

“Our roads aren’t safe. Our bridges aren’t safe. Our dams aren’t safe,” the first-term Democrat said. “And we need to make sure we’ve gotten enough water resources for the future.”

Looming over those and other priorities, however, as the governor and legislative leaders readily admit, is public education – from early childhood through to college and university.

Policy makers are paying closer attention to how New Mexico educates at-risk students who make up the majority of the state’s public school population.

So expect a reprise of 2019, of sorts, when state leaders pumped half a billion dollars into the system after a historic ruling in the Yazzie-Martinez court case found New Mexico guilty of not providing a sufficient education for low-income students, many of whom are English language learners, Hispanic and Native American.

“We have an incredible opportunity to address huge deficiences in our education system,” said Sen. Majority Leader Peter Wirth, D-Santa Fe. “When you have resources like this, this is the chance to get ourselves out of the hole we’ve been in as a state.”

It’s hard to predict the return or not of a back-room, weeks-long debate that enveloped lawmakers in 2019. The conversation pit those who lobbied for more sweeping reforms that prioritize multicultural education – as called for by plaintiffs in the Yazzie-Martinez lawsuit – versus those who advocated for directing more dollars to existing programs and teacher pay raises.

House Speaker Brian Egolf, D-Santa Fe, however, said it’s not going to be “either or” this session, but “yes, all.”

Lujan Grisham also is asking state lawmakers to make college tuition free for New Mexicans.

If she gets what she wants – there is some debate over the cost – it would position New Mexico in the middle of a national trend, according to Kate O’Neill, the governor’s secretary of higher education. Twenty states have adopted the approach and another 10, including New Mexico, are eyeing it, O’Neill told the crowd in Albuquerque.

But policy makers are looking to square more than public education when they meet in Santa Fe. Lujan Grisham wants to fully staff state agencies. Some departments have 40% vacancy rates, she told her audience.

And the wish list grows when you survey legislative leaders and rank-in-file state lawmakers. The state’s pension systems require a cash infusion, some say. And roads around the state need improving, especially in the southeast where traffic from the oil boom is worsening already-bad roads.

“I will be pushing for (additional money) for roads and bridges” to supplement the state’s transportation fund, said Rep. Patricia Lundstrom, D-Gallup, whose committee drafts the state budget each session. The transportation fund “is not even close to keeping up with the needs.”

The discussion over what will receive funding will parallel the usual push-pull over how much of the state’s surplus to save for years when the economy deflates tax revenue. New Mexico’s finances historically have mirrored the boom-bust cycle of oil and gas, the state’s largest industry. And there are those – Sen. John Arthur Smith, D-Deming, and Sen. Minority Leader Stuart Ingle, R-Portales, come to mind – who advocate for tucking away as much as possible for the busts that always follow the booms.

“We’ve got so much money coming in now we have to be careful what we set up on reoccurring revenues and make sure of our reserves,” said Ingle. “The oil market is going to fall off. We have to watch how we spend or we’re going to be in trouble.”

Indeed, there are signs of volatility. While no one disputes that New Mexico is sitting on reserves the U.S. Geological Survey characterized as the largest the federal agency had ever seen, in December state economists lowered the estimate of new money available to craft next year’s state budget to $800 million, down from $900 million from an earlier prediction.

The downgrade reflected the ups and downs of drilling activity in the Permian Basin that straddles New Mexico and Texas, which is responsible for New Mexico’s fulsome economic picture.

That volatility makes some skittish about the state’s predilection for counting on too much from the oil and gas industry.

“It’s a world commodity and it is subject to economic whims globally,” said Smith.

But in response, some legislators say the state should focus on creating state revenue from a variety of sources so New Mexico isn’t so vulnerable to the world oil market.

That will lead state lawmakers to a question they return to every year: How do you diversify the state’s economy to provide essential services and reduce the pain when the oil busts inevitably follow the booms.

Ideas likely to log debate time with state lawmakers include a proposal to legalize recreational cannabis, which supporters say would generate new tax revenue, to one that would call for raising the tax rates on the wealthiest New Mexicans.

How to reform the state’s single biggest levy, the gross receipts tax, likely will log some debate time, too.

Overlaying the policy discussions, and the politics that inevitably will come with them, will be the 2020 election, less than a year away and already generating buzz.

That, in turn, might magnify a central theme of the 2019 session that some say will only be sharpened in an election year: the rural-urban divide.

During the 2019 session, for example, the Democratically controlled Legislature passed gun legislation signed into law by Lujan Grisham that generated significant pushback from sheriffs in the state’s mostly rural counties.

“Their concerns are so different,” said Sen. Gerald Ortiz y Pino of Albuquerque. “Their problems are so different. The revenues that each generates are so different. It’s always a question of ‘well, if we do this for you, it’s going to mean less for me.’”