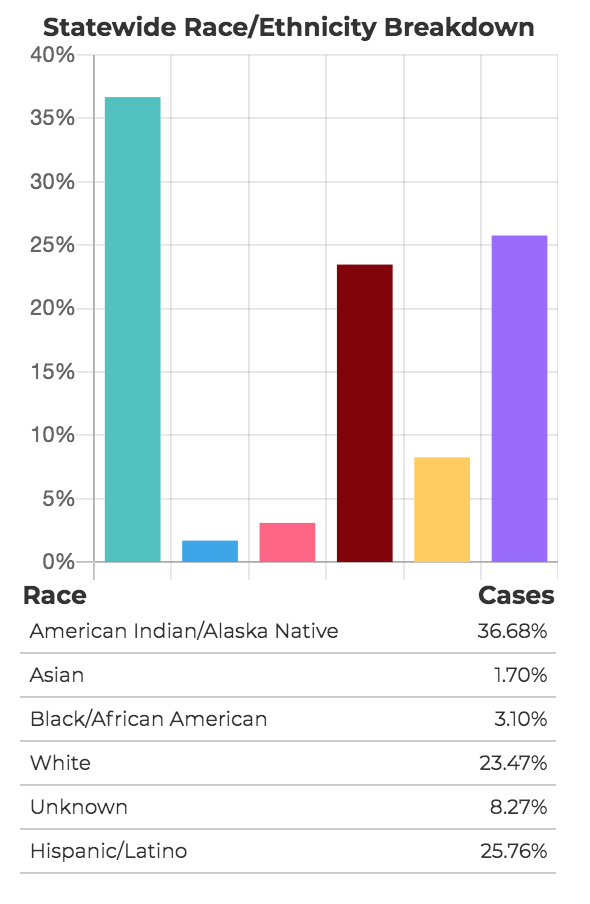

Native Americans make up almost 37% of the positive COVID-19 cases in New Mexico, more than three times their representation in the state’s population. That’s according to a new data dashboard the state Department of Health unveiled today.

Native Americans represent around 11% of the state’s 2 million residents. In comparison, Anglos, who make up 37 percent of New Mexico’s population, represent just under 24% of the state’s positive cases. And Hispanics, 49% of the population, represent just 27% of the positive cases.

Also disproportionately affected, but by a much smaller margin, are African Americans, who make up 2.6% of the statewide population, but 3.1% of COVID-19 cases. The data does not include a race or ethnicity breakdown by county, hindering analysis of how particular racial or ethnic groups are affected at the local level.

New Mexico In Depth began asking weeks ago for race and ethnicity data of those who’ve been tested and contracted the virus. On Sunday, we published our own calculation from publicly available data that 31% of the state’s positive cases involved Native Americans. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham on the same day said on a national news program the percentage was 25%. As it turns out, it’s higher.

The reasons for the high prevalence found in Native American communities are many, said Dr. Gayle Dine’Chacon, director of the Center for Native American Health at UNM and former surgeon general of the Navajo Nation.

Native Americans tend to experience high disparities in social determinants of health, including a basic lack of infrastructure. There’s a significant percentage of people without running water. That makes it more difficult to practice a primary preventive strategy: Washing one’s hands frequently. Other factors include lack of funding for Indian Health Services. A lack of funding for education and for housing, with multiple generations of families living under one roof, also contribute.

It’s that last piece that Dine’Chacon says is particularly difficult, as tight-knit, multi-generational living arrangements are generally seen as positives in native communities.

“This virus has proven to go against how we think of our protective factors,” Dine’Chacon said of the multiple generations who often live under one roof. “The safest place we can be is in our house.”

But ultimately, the root of the high prevalence has a lot to do with lack of planning at the beginning, Dine’Chacon said, noting that a plan was quickly implemented to lock-down nursing homes early in the crisis. It’s well-known that tribal communities have the highest risk factors for some chronic illnesses, like diabetes, in the state, she said. Such underlying chronic diseases are high predictors for COVID-19 deaths.

Tribal communities needed more public education, early on, about public health measures like social distancing and stay at home orders meant to mitigate the spread of “an unseen enemy.”

“A plan would have been best implemented earlier, but a plan didn’t come out until about a week ago,” said Dine’Chacon about a tribal response plan made by the state Indian Affairs Department last week. “A month ago would have been better, the day the stay at home orders were implemented, having that for specific tribes and communities.”