As the state gradually reopens from its coronavirus closure, it’s not only nurseries, bike shops and clothing stores that must figure out how to do business while maintaining social distancing—county clerks across the state are conducting their first primary election during a pandemic. But the number of polling places has been slashed, mail service has been interrupted in some areas and voting advocates are concerned that there will be folks, especially in Native American communities, who could be left out.

Indian country has been hit hard by COVID-19, as NMID reported in mid-May. Native Americans represent 58 percent of the state’s cases. As a result, many Pueblo and tribal governments have closed their lands to non-residents and established curfews in an effort to slow transmission of the virus. In some cases, those closures have interrupted mail service.

“We’re worried,” says Ahtza Dawn Chavez, the executive director of the NM Native Vote. None of the options available—voting by mail, voting early or going to the polls on election day—is free of deterrents or risk, especially for voters in remote areas where the virus has spread rapidly.

“This is a huge group of people that we have historically disenfranchised and we’re doing it again,” says Heather Ferguson, executive director of Common Cause NM. “We have some catastrophically bad problems and people have been calling us because they want to vote.”

After the state supreme court on April 14 rejected a request by 27 of the state’s 33 county clerks’ to hold the election entirely by mail, the secretary of state’s office mailed absentee ballot request forms to all registered voters and distributed hand sanitizer and masks to polling stations.

Researchers from Common Cause have found significant barriers to access for voting in person and by mail. Four Pueblos that closed their borders to non-residents, Santa Ana, San Felipe, Cochiti and Zia, each notified election officials that they would not host early voting sites.

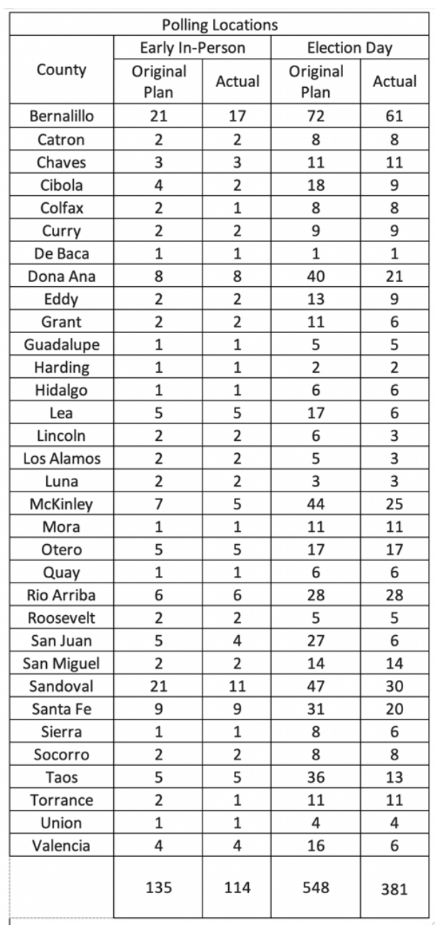

All four of those pueblos are in Sandoval County, which originally planned to open 21 early voting centers. That number dropped by nearly half, to 11.

“Some communities had requested early voting sites, but the law says that any registered voter can vote at those sites,” says Chavez, who is a member of Kewa Pueblo. Inviting any member of the public into a tribal community to vote goes against the goals of closing borders to minimize the spread of the virus. That made for some difficult decisions. “These are sovereign nations. If they close their borders off, they close them,” she says. “Now we’re trying to figure out where these community members can vote.”

Statewide there are 21 fewer early voting locations and 167 fewer sites open on election day than usual, according to figures provided by the secretary of state’s office.

McKinley County went from seven polling sites to five. Cibola County, which includes Laguna and Acoma Pueblos, plus part of the Ramah Navajo Reservation, normally has two early vote sites on tribal land, but it cut those and now has just two, in Grants and Milan.

San Juan County, which covers part of the Navajo Nation in the northwest corner of the state, usually has 32 voting convenience sites between early voting and election day, but that number has been reduced to nine in order to increase safety for poll workers and voters, says Arlenta Horse-Dickie, the liaison for the Native American Elections Information Program in the San Juan County Clerk’s Office.

Horse-Dickie says she isn’t concerned that having fewer polling places will make it hard for some to cast a ballot, especially since the clerk’s office sent letters to residents letting them know where they can vote. “Everything seems the same,” she says.

Horse-Dickie is also in charge of making sure each polling station around the Navajo Nation is staffed with a translator who can help voters who aren’t comfortable reading a ballot in English or Spanish. In a normal year, there would be one translator at each of 13 stations on the Navajo Nation, helping an average of 500 people who request the service. This year translators will be at four sites, the two on the reservation, one in Kirtland and one in Bloomfield, but Horse-Dickie said she’s confident that’s enough.

Chavez is concerned that voting among Native Americans is down. “Usually at this point in a primary election we’re seeing much higher turnout,” she says. And she thinks she knows one reason why: “People are having to drive a lot farther to early vote.”Horse-Dickie says her office has been getting more calls than usual about voting absentee, and that she thinks more people will make that choice. “Right now everybody is saying if I’m going to vote I have the [absentee ballot] application right here.” Already, absentee voting is up more than 325% over the 2016 primary election. As of May 26, over 98,000 New Mexicans had voted by mail, while nearly 31,00o had voted early in-person. By comparison, in the 2016 primary, just over 23,000 voted absentee, while more than 117,000 voted early.

“We fully expect well over half of the votes cast to be absentee,” this time, says Alex Curtas, communications director for Secretary of State Maggie Oliver.

As High Country News reports, requesting a ballot and voting by mail can be more difficult for those who live on tribal land where they don’t have a street address and must drive a significant distance to reach a post office box.

“I have family in Sanostee [on the Navajo Nation] and my aunt has a Fruitland mailbox,” Chavez says. It’s a 50-mile drive just to get the mail, and her aunt doesn’t usually make the trip more than once a week, she says.

On Zia Pueblo the U.S. Postal Service has been prevented from delivering mail, Ferguson said, forcing residents to drive 20 miles to a post office in Bernalillo to pick up and drop off mail.

Even in metropolitan areas there can be mail hiccups. “It took nine days for my absentee ballot to get from the Bernalillo County Clerk’s office to my house in the Northeast Heights [of Albuquerque],” Ferguson said after tracking her ballot using the secretary of state’s website. Her office has heard complaints of ballots taking two weeks, she said.

The deadlines for voting by mail are hard and the rules are strict. Absentee ballot applications must be received by the county clerk’s office by 5 p.m. May 28. That’s five days before the election. Horse-Dickie says voters requesting ballots that late probably won’t have time to return them by mail, so they should plan on bringing them in to the clerk’s office. Ballots can be delivered in person only by the voter, a member of their immediate family or a caregiver, and they absolutely, positively must be there by 7 p.m. on election day, June 2.

In Chavez’s aunt’s case there is an early voting center close to Sanostee, in Newcomb. Along with a site in Shiprock, it’s one of only two sites on the Navajo Nation.

That doesn’t sit well with Chavez, whose goal is to get out the vote. “If we’re trying to advocate for social distancing in the area that has the largest per-capita infection, why do we have fewer polling places?” she asks. With coronavirus numbers leveling off but holding steady, people who normally carpool or accept a group ride to the polls might reasonably be reluctant to share a car. And once they get to the polls they might be turned off by long lines caused by social distancing rules inside, she says.

Election officials pushed for an all-mail election because they believed it would be safest, particularly for poll workers, who tend to be older, Curtas says. With that option off the table, they are taking steps to minimize the risk for voters who want to cast a ballot in person.

The state received more than $4.6 million in state and federal emergency funds from the CARES Act for promoting absentee voting—and buying sanitizing supplies for polling places. Every in-person polling place will be equipped with PPE for poll workers and masks for individual voters, Curtas says. Poll workers will be wiping down surfaces, wiping down the pens.

“I feel like we have plenty of protection,” Horse-Dickie says. “It’s going to be a safe environment and they can come in and get the assistance that they need.”

Ferguson is not so sanguine.

“I was surprised about how little we’ve known about the issues [Native voters] face,” Ferguson said. “We have some major gaps in the system that we have to fix before November.”