The pandemic legislative session (as it will go down in history) lived up to its name just a week in, with at least one House Republican lawmaker and four Roundhouse staff testing positive for COVID-19. Given that lawmakers aren’t required to be tested, there may be more.

Democratic House Speaker Brian Egolf said he was “dismayed” Republicans had a catered lunch, a characterization Republican House Minority Leader Townsend disputed to the Santa Fe New Mexican. Townsend urged delay of the session before it began, and is now calling for a temporary halt.

It’s not surprising there’s been a COVID outbreak at the Roundhouse. We are in the midst of a deadly pandemic that has killed more than 3,200 New Mexicans in under a year, closed schools and businesses, and created untold anxiety and stress.

Should the Legislature be meeting? It’s questionable. But underway it is, supported by House and Senate leadership, and the governor. The idea is that lawmakers work predominantly online, convening for floor sessions during which just a fraction of lawmakers will be in the chamber. Everyone is to debate bills online, regardless of where they are physically located.

While there’ve been some technology hiccups, the process is in full bloom this week, with major legislation having already cleared first committee hearings. I’ve been watching and have to say, as someone who finds legislative webcasting invaluable, the use of Zoom has improved the virtual offering immeasurably. The sound is leaps and bounds better and one can see documents being presented.

As to public participation, how can a virtual session possibly replace the opportunity for the general public to be physically present with lawmakers? It can’t.

The annual event that finds lawmakers conducting the public’s business in the presence of a throng of New Mexicans, now finds those New Mexicans largely cut out, other than the opportunity to give statements during public comment sections of hearings. And that’s a space that one subset of the public — 577 registered lobbyists so far — has stepped right into. Watching the proceedings this week, I’ve been able to hear them, loud and clear.

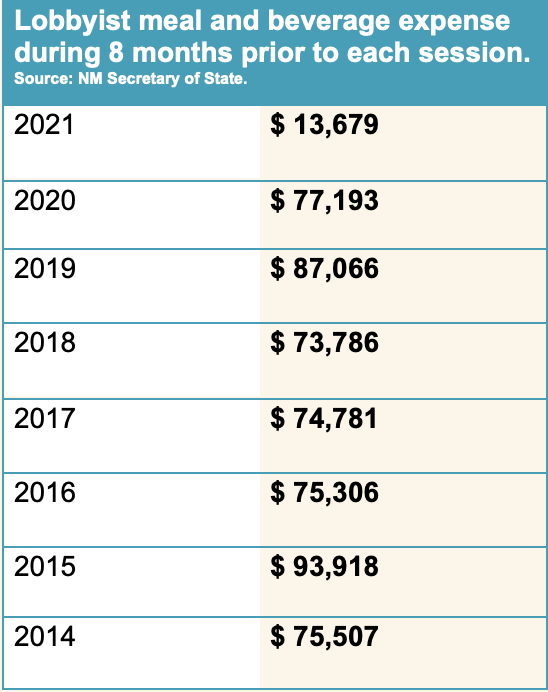

Still, lobbyists have been shut out of a legislative process that in normal years allows them to waylay lawmakers in Roundhouse hallways and offices. One indication their profession has changed dramatically is a steep drop in dollars they spent on meals in the eight months prior to the session.

Normally, lunches and dinners are a year round activity. As one session ends, lobbyists pivot to considering interim meetings of the Legislature and the next session. The meals go on as a routine matter. But in 2020, lobbyists reported spending just a fraction of what they spend in normal years.

The disruption in the normal routine, if these figures indicate anything, has been severe. But maybe it’s not all that big of a deal.

Lobbyists describe taking lawmakers out for a meal as a means to an end: it helps them cultivate relationships and provide information to lawmakers. But lawmakers we’ve spoken with say the money spent on meals isn’t all that important.

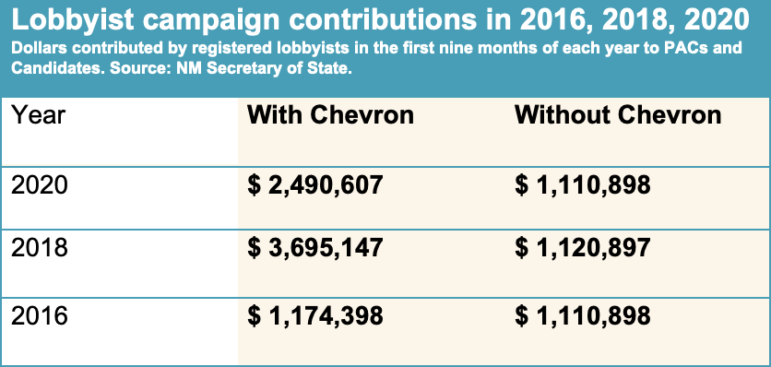

Former Senator Dede Feldman told New Mexico In Depth the real power lobbyists and their employers have is using money to influence elections, and “preordain what the verdict will be before even starting the actual lobbying process.”

From this perspective, the lobbying power play is in election spending, not wining and dining. By that measure, lobbyists and those who employ them worked full force to maintain their power during the 2020 election.

I took a look at lobbyist political contributions during the thick of the 2016, 2018, and 2020 election cycles. Oil giant Chevron has been the biggest player in each of those elections, making large contributions to PACs, in particular. The following chart shows the spending reported by lobbyists in May and October of those election years, with and without the Chevron spending.

Chevron, a lobbyist employer, has become a big spender in elections in recent years. In 2018, the company shook the election landscape with a $2.5 million donation to a political action committee. In 2020, the company made a substantial donation to a political committee running a primary campaign, and also spread more than $700,000 to elected officials. When removing Chevron, the political contributions reported by all other lobbyists have hovered at a little more than a million annually since 2018.

These numbers show that the 2020 pandemic did not slow the efforts of lobbyists to influence who sits in powerful legislative and other elected positions. And the numbers aren’t even the complete picture. These are just the dollars that big money interests have given through their lobbyists. There’s another $500,000 out there that companies and organizations that employ lobbyists have reported separately to the New Mexico Secretary of State’s office.

This story first appeared in a New Mexico In Depth newsletter. Sign up to receive our newsletters through email.