Three years ago, New Mexico incarcerated about 7,400 people. Since then, the prison population has dropped, mirroring a national trend. It’s estimated that by 2025 the average prison population could be 4,938.

The reasons for the declining prison population are unclear, according to a report prepared by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of New Mexico for the New Mexico Sentencing Commission.

But if that trend continues, legislative analysts say, the Department of Corrections would have to find just 456 new beds, on average, if New Mexico were to end the use of private prisons after more than two decades and transfer all privately held prisoners to public facilities by 2025.

The statistic is buried in a legislative analysis prepared for lawmakers considering legislation introduced by Rep. Angelica Rubio, D-Las Cruces, the latest attempt to end New Mexico’s use of private prisons.

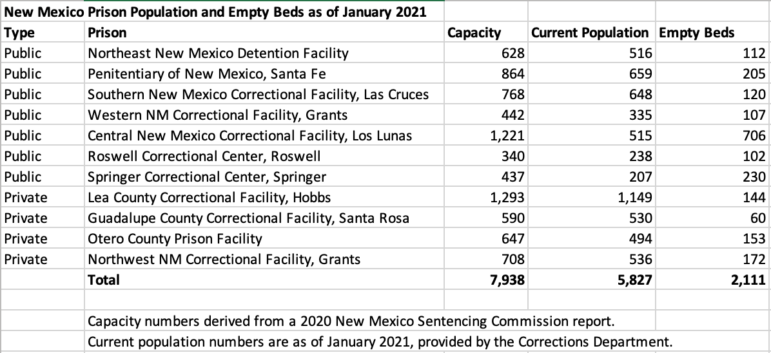

The opportunity is being driven by the state’s seven public prisons, where more than 1,580 beds sit empty, compared to the almost 530 unused in the four facilities operated by private companies.

In effect, by 2025 there could be so much room at the state’s public prisons if there continues to be a decline in population that New Mexico could transfer most of the prisoners housed by private prison operators — there are a little more than 2,700 now — and need to find only 456 new beds, or about 14% of private prison capacity. New Mexico could build additional housing units at a public prison or purchase one of the privately operated facilities, legislative staff note.

“We should never be profiting from people and their bodies,” Rubio said during a committee hearing on HB 40. It calls for the state to phase out the state’s use of prison corporations as contracts with those corporations end.

Ending the use of private prisons would be a significant change. Only 8% of inmates nationally were incarcerated in privately run prisons as of 2017, compared to 46% in New Mexico this year, according to the legislative report. That’s the highest rate among states, according to the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization focused on prison reform.

Today, two companies, GEO Group and CoreCivic, dominate the industry nationally, raking in a combined $3.5 billion in 2015.

The two play a similar role in New Mexico, operating three of the four privately run prisons.

GEO Group operates Guadalupe County Correctional Facility in Santa Rosa and Lea County Correctional Facility in Hobbs, which is the largest prison in the state. CoreCivic operates Northwest New Mexico Correctional Center in Grants and Management and Training Corporation, another private prison company, operates Otero County Prison Facility in Chaparral.

Over the years, private prisons in New Mexico have faced scrutiny on several fronts, including security and safety issues stemming from cost-cutting measures. Private operators keep expenses down by employing mostly non-union and low-skilled workers and paying lower wages with limited benefits compared to public prisons, according to the Sentencing Project.

Supporters of Rubio’s legislation at its first committee hearing in late January called out poor conditions: delayed medical treatment, poor food quality, freezing nights. Hilaria Martinez’s husband got sick while incarcerated at Otero County Prison Facility and was never seen by a medical provider, she said. He and their family were traumatized by his incarceration and the poor conditions he endured.

“They don’t see us as human. They only see how much money, profit they can get from our suffering and, sometimes, our lives,” Martinez told lawmakers.

Rubio’s bill is part of a larger movement that has seen a handful of states ban private prisons in recent years, including California, and the decision by President Joe Biden last month to end the Department of Justice’s use of privately run federal prisons. The Trump administration and GEO Group, one of the largest prison corporations in the country, sued California last year, arguing unsuccessfully that the law is unconstitutional.

But the potential economic harm to local communities that rely on the gross receipts tax and jobs provided by the industry if New Mexico shut down private prisons is raising bipartisan alarm among state lawmakers.

A better approach, said Rep. Randall Pettigrew, R-Lea County, would be for the Legislature to form a working group to study and develop a transition plan to help communities that have come to depend economically on private prisons. Those concerns prompted amendments to the legislation by the House Judiciary Committee to create two funds to help counties and workers adjust should private prisons be closed. Those changes to the bill garnered it a third committee hearing in the House, further imperiling its chances of success in 2021.

Private prison safety problems

One critique of private prisons is their relative dangerousness when compared to public facilities. A 2016 report from the Department of Justice found that private prisons contracted to hold prisoners for the federal government were more dangerous than their federal counterparts. Private prisons had a 28% higher average rate of inmate-on-inmate assaults and more than double the rates of inmate-on-staff assaults compared to public prisons, as well as higher rates of use of force by staff.

Similar critiques have been made about New Mexico’s private prisons, which also note staffing levels don’t always meet contractual obligations, contributing to potentially dangerous situations. Holding private prisons accountable for keeping adequate staffing levels has long been a problem in New Mexico.

In the 2000s under Democratic Governor Bill Richardson, prison corporations operating in New Mexico rarely faced fines for contract violations regarding staffing levels. Joe Williams, the corrections secretary at the time, had been employed by GEO Group before working for the state, and went back to work for the company after former Republican Gov. Susana Martinez took office. During his tenure as corrections secretary, Williams was scrutinized for his decision not to fine GEO for understaffing, despite the Legislative Finance Committee finding that there were potentially millions each year to be collected.

After Martinez’s first year in office, private prison companies were facing almost $1.6 million in penalties for understaffing and other contract violations. In 2011, the Corrections Department fined GEO Group $1.1 million for understaffing at the Lea County Correctional Facility.

In 2017, a violent riot broke out at Northeast New Mexico Correctional Facility, a prison in Clayton run by GEO Group and, according to a lawsuit filed by an inmate who had his throat slit, the facility wasn’t adequately staffed — 20 guards were supposed to be on duty but only nine were working.

In June 2019, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham announced the state would take over the prison and the Corrections Department fined GEO $2.7 million over a two and half year period for failure to properly staff the prison.

Meanwhile, the American Civil Liberties Union of New Mexico regularly receives complaints regarding the conditions incarcerated people are kept in, Nia Rucker, policy counsel and regional manager of the Las Cruces ACLU office, told the House Consumer and Public Affairs Committee.

“These complaints range from cost-cutting measures that result in preventable illness and permanent injury, all the way to violent conditions that result in death,” Rucker said. “Private prison contractors are inherently incentivized to maximize profits at the expense of those involuntarily in their care. These contractors’ primary duty is to their shareholders rather than to New Mexicans.”

In trying to hold private prisons accountable, there are unique barriers compared to state-run prisons, including the legal resources prison corporations have, said Wanda Bertram, spokesperson for the non-profit research and advocacy organization Prison Policy Initiative.

“We all know that prisons in this country are full of human rights abuses and we need our elected officials to be taking accountability for that because when big corporations take accountability, they’ve got well-funded legal teams that they can use to bat down these lawsuits and stay in business,” Bertram said.

The industry also works to maintain its influence through campaign donations. In 1998, Wackenhut Correctional Center, now GEO Group, donated $9,330 to Republican Governor Gary Johnson’s re-election campaign. In 2006, the company gave more than $43,000 to former Gov. Richardson’s campaign, and spread more around to other New Mexico politicians. And since 2010, private prison operators have given almost $300,000 to New Mexico candidates and political action committees, mostly from GEO Group, a review of campaign reports filed with the New Mexico Secretary of State shows.

Projections about need for beds aren’t so cut and dried

The legislative analysis of Rubio’s bill highlighted how many beds would be needed on average in 2025 to consolidate all prisoners in public facilities, on average. Last month, based on capacity for each prison facility and the prison population, there were 2,111 empty beds, most in public facilities.

One caveat is that consolidating prisoners into publicly run prisons is not as simple as moving people around the system, according to the legislative analysis. Some offender groups are held in private prisons that would need to be kept together — specifically at the Otero County facility where sex offenders and ex-law enforcement personnel are held.

But there’s also the challenge of sorting through the difference between the average number of beds needed in 2025 and the number of beds necessary on any given day when the prison population soars. In 2025, the highest occupancy level on a given day could be 6,402, which is about 1,700 higher than current public prison capacity, according to the New Mexico Sentencing Commission.

Corrections Secretary Alisha Tafoya Lucero spoke against Rubio’s proposal, saying the department would lose 3,000 beds. Eric Harrison, spokesperson for the Corrections Department, said the secretary was referring to the private facility total bed capacity of 3,278.

But Tafoya Lucero signaled support for reducing the state’s reliance on private prisons. “When it is safe and reasonable to convert a private facility into a public facility, we absolutely will,” she said.

Responding to a question from New Mexico In Depth about whether there’s a plan in place to convert private facilities, Harrison said, “When fiscally responsible, we are willing to transition from private to public as we did in 2019 with the Northeast New Mexico Correctional Facility. It boils down to budgets and being able to forecast what our resources will look like in the coming years.”

A spokesperson for CoreCivic wrote in an email that ending the use of private prisons in New Mexico would “lead to more overcrowding, higher costs and less reentry programming. If in the future contractor-operated correctional facilities aren’t needed, state officials can simply end the contracts.”

GEO Group did not respond to a request for comment.

A 2014 state-level survey by In the Public Interest, a national research and policy organization that studies privatization of public functions, found that evidence is lacking that private prisons save states money. The report noted that the costs of incarceration may vary between private and public facilities due to contract provisions. It gave one example from New Mexico. Between 2001 and 2006, annual spending on private prisons increased by 57%, despite the prison population increasing by only 21%. The increase was mostly due to automatic contract price increases.

What about jobs?

Looming over the debate is another problem that’s more thorny and difficult than finding enough beds: Four smaller, more rural counties in New Mexico rely on significant tax revenue generated by private prisons and the jobs they provide.

The legislative analysis gives a concrete example: When CoreCivic pulled out of Torrance County in 2017 because, it said, it didn’t have enough prisoners to make the business viable, “200 employees lost their jobs, families relocated and the local school district lost a significant number of students. The only grocery store and bank in Estancia also closed.” The facility has since reopened after the county contracted with CoreCivic to hold migrant people for the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. According to legislative staff, CoreCivic pays approximately $100 million in gross receipts tax and employs 150 people.

Rep. Stefani Lord, D-Sandia Park, told lawmakers during the House Consumer and Public Affairs that Estancia’s mayor told her the town would lose two-thirds of its income if the prison closed. “We can say goodbye to Estancia,” she said.

Harry Garcia, D-Grants, told lawmakers his community is highly reliant on two privately run prisons, one that houses federal immigrant detainees and another for state prisoners. If those prisons closed, “…we’re going to lose around 350 jobs right off the top. We’re gonna lose about $25,000 in property tax,” he said. Garcia elaborated that those jobs support around 1,000 in Grants, which has lost several other major employers recently, a power plant and a refinery.

Rep. Harry Garcia, D-Grants, speaking about private prisons during the House Consumer and Public Affairs committee hearing, Jan. 28, 2021.

“Down the line it’s going to have to happen but we need to plan it out not just dump it on somebody right now,” he said about the effort to cease using private prisons. “We need to take into consideration the people that are going to be affected.”

But Nathan Craig, a New Mexico State University anthropology professor serving as an expert witness for Rubio, argued that the benefits of prison corporations to local economies don’t always live up to their promise.

Prison corporations frequently try to get out of paying gross receipts tax, Craig said. GEO Group and the state Taxation and Revenue Department went to an administrative hearing late last year over GEO’s debt of $14.7 million in gross receipts tax, $2.9 million in civil penalty, and $1.8 million in interest. The civil penalty fine was dropped, but GEO was ordered to pay the remaining total of about $16.6 million.

Craig also said that in many rural prison settings, the majority of the staff commute from the nearest metro area, which in some cases is out-of-state. The bulk of the workforce at Otero County Prison Facility, for example, comes from El Paso, he said.

The jobs that private prisons do provide aren’t as good as those at public prisons, Carter Bundy, with the trade union AFSCME that represents correctional officers at state-run prisons, said during a committee meeting.

“When the state took over the Clayton facility, instantly people who were correctional officers there got $3 an hour raises, they had better health care, and they had pensions. All that money stays in the state of New Mexico,” Bundy said.

The Associated Press reported that a correctional officer at the Clayton facility was paid about $15 an hour, while officers at state-run prisons make more than $17 an hour.

Addressing concerns that the bill would force communities to transition away from private prisons too quickly, Adriel Orozco, an attorney at the New Mexico Immigrant Law Center and one of Rubio’s experts, said that the bill gives communities several years to make a transition.

“Simply put, existing contracts will run until they expire. Because all current contracts expire in between three and four years, the state and local communities won’t be impacted immediately and will have time to assess local impacts and options, to plan for a just transition,” Orozco said.

But lawmakers in both the House Consumer and Public Affairs and the House Judiciary committees argued that there should be a more robust transition plan in place before the bill passes.

The Judiciary Committee amended the bill to include two special funds, one to help counties where private prisons would be closed to develop their economies, and another to help displaced workers.

Rubio expressed optimism even if the bill doesn’t make it to the governor’s desk this year, saying the measure was part of a larger criminal justice reform effort.

“Private prisons will end,” Rubio said at the first committee hearing. “That’s my promise as a legislator. If it’s not this year, it will happen.”