Despite some early optimism from advocates, state lawmakers took a pass this year on requiring greater transparency around the work of lobbyists. In fact, lawmakers didn’t even give the topic a full hearing during the recent legislative session. That’s despite a significant lack of disclosure about how powerful lobbyists work to influence legislation in New Mexico. In a 2015 report, the Center for Public Integrity graded the state an “F” for lobbying disclosure, the 43rd worst in the country. It’s not improved since then.

Drive a few hours north, and the sort of transparency proposed for New Mexico is just business as usual.

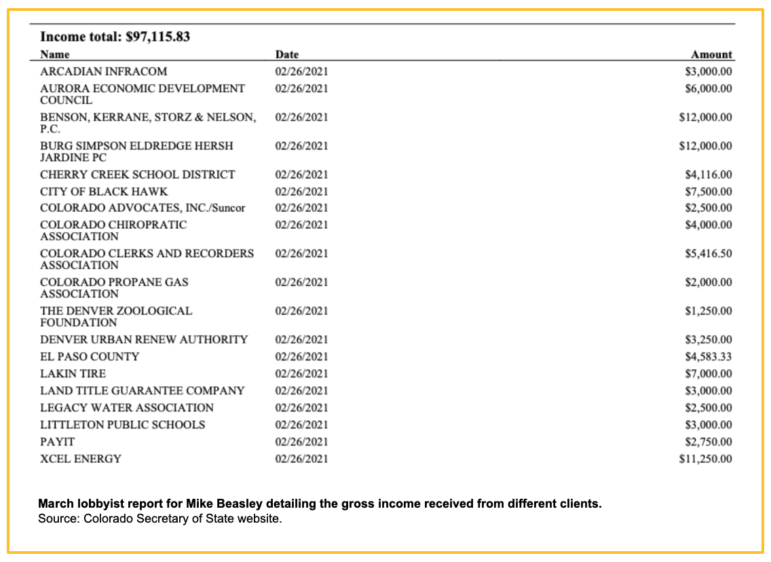

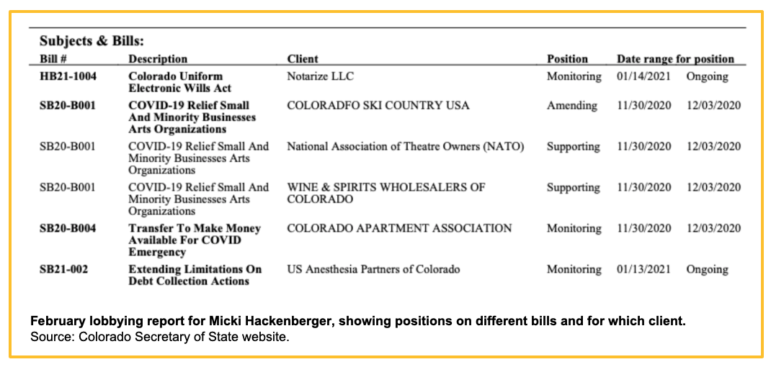

In Denver, lobbyists file monthly reports detailing their income from lobbying, which bills they’re lobbying on, which of their clients has directed them to lobby on that bill, and whether they are supporting, opposing, amending, or monitoring the legislation.

Whenever a lobbyist starts working on a new bill or changes positions on an existing bill, they report that change within 72 hours.

Additionally, a 2006 constitutional amendment banned lobbyists from giving gifts to lawmakers, which means most of the “wining and dining” that exists in Santa Fe is prohibited in Denver.

The constitutional amendment also prohibits statewide elected officeholders from becoming lobbyists for two years after leaving office.

But it wasn’t always this way.

Morgan Carroll, then a freshman state representative, introduced a bill in 2005 to give injured workers a choice in physician. Though she believed her bill to be popular with constituents, over 200 lobbyists came “out of the woodwork” to oppose the bill, she said, leading to its demise.

“I almost didn’t run again, I was so crushed,” said Carroll, who is now the chair of the Colorado Democratic Party. “The influence and the power of the lobby corps was something that nobody had prepared me for.”

Carroll said that experience underscored the need for greater transparency in Colorado’s legislative process, leading her to introduce a bill the next year that required disclosure of lobbyist compensation and the requirement that lobbyists report their positions on bills.

“Inside the building, everyone was used to the way business was done, and that crossed party lines,” said Carroll. “So when people got to where they were, and learned how to be effective under the current system, people were starting to get very defensive.”

In Morgan Carroll’s telling, Denver closely resembled Santa Fe before legislators and citizens took action to make change.

“They would feed people, they would send in lunch, they would send in dinner, they would do receptions. We had colleagues that would be going to receptions at night instead of reading their bills,” Carroll said. “The power imbalance was very much a thing. If you want people to have confidence in the government, they need to be able to see everyone that is paying anything to influence their own government.”

Carroll said she ran an “outside the building” strategy for the bill, organizing petitions and ensuring that the press would cover the process so that the public could weigh in.

“When cameras were in people’s faces, they found their way to yes.”

That 2006 lobbying bill laid the groundwork for disclosure regulations that continue to today, with lawmakers building upon the system in 2014 and 2019. And lobbyists, it seems, have come to live with it. In fact, some describe the greater disclosure as beneficial.

“There really aren’t a lot of complaints,” said Mike Beasley, President of 5280 Strategies, who’s been lobbying in the state since the 1990s and currently has 22 registered clients. “My dad stopped buying dinner when he found out how much money I make. That’s the one downside of the law.”

“Like everything, when it’s new, it will be full of potholes, and then you figure out how to fill the potholes to make it run a little smoother,” said Jim Cole, the owner of a lobbying firm called Colorado Legislative Strategies. He said the Colorado Secretary of State’s office often seeks input from lobbyists to find ways to make reporting easier.

One argument frequently made in opposition to increased disclosure in New Mexico is that it would be excessively burdensome for lobbyists. Rep. Greg Nibert, R-Roswell, said in 2019 that giving lobbyists 14 days after the session to report which bills they worked on would be difficult due to dealing with “exhaustion.” His concerns were echoed by other lawmakers.

But in Colorado, they’ve learned to adapt.

“It takes me literally maybe 15 or 20 minutes a month,” said Beasley, who only has to report for himself. Larger firms may have more of a reporting burden, but often employ staff to deal with it.

“It’s easy if you’re a single person shop and you’re only reporting yourself. It’s a little more complicated when you have a lobbying firm, and then you have multiple people,” said Micki Hacknenberger, president of the lobbying and consulting firm Axiom Politics. “But it’s just time consuming, and honestly, that’s just what we do now.”

“I’ll probably report as a ‘monitor’ when I first look at a bill,” said Hackenberger. “I’ll change my position when I get feedback from my client, which is generally within 24 hours. And then once I have a position, I’m going to go and talk to legislators.”

“I’m guessing she’s spending an hour a day reporting various positions,” said Cole, referring to his office manager. “It depends on how many clients you have.”

Another fear expressed in New Mexico over the years is that greater disclosure will dampen public participation in the legislative process or harm a lobbyists’ effectiveness. But the monthly reporting in Colorado may help people work together better.

Cole said that publicly disclosing bill positions makes it clear to other lobbyists and legislators where everyone stands on a particular bill, allowing for natural give-and-take to happen.

“They say, well, what can you do to amend that? It initiates a dialogue,” said Cole.

To support the disclosure system, the Colorado Secretary of State maintains a website where the public can search for lobbyists and their clients, view how they’re being paid and which bills they’re engaging on, and even search by bill numbers.

For example, a bill that would establish a “Prescription Drug Affordability Review Board” has led upwards of 100 lobbyists to state their position on the legislation, which the public can see by searching the bill number on the Secretary of State’s website. This allows the public to know how different interest groups view the legislation.

“I think it’s a great feature for legislators and other lobbyists,” said Hackenberger, explaining that the system allowed different groups to work out differences out in the open.

“It has led to more dialogue, more honesty, more transparency about who’s doing what and why,” said Beasley. “I think the public has a right to know what we make, and I know that’s not very popular with lobbyists in other states, but we’re quite used to it here. The sun came up this morning, and it does work pretty well.”

As for Carroll, she says the system has brought much-needed transparency to the process, empowering citizens primarily by exposing lobbyist’s positions to public scrutiny.

“It makes people think twice about the positions they’re going to take,” she said. “I also think it makes it clearer for people who are trying to organize citizens.”

“Is it a pain? Yeah, it’s a pain,” said Hackenberger. “But I mean, it’s a pain we live with in the name of transparency and disclosure.”

New Mexico lawmakers snub transparency

Current lobbying regulations in New Mexico provide some benefit to citizens.

People must register as lobbyists if they’re conducting a particular activity defined by the state as lobbying. When they register, they have to name what group they represent. They’re barred from donating money to lawmakers during the legislative session, and lawmakers aren’t supposed to accept gifts exceeding $250 in value. And the Secretary of State maintains a portal where users can see certain expenditures and political contributions for the current year.

But compared to much of the country, New Mexicans sit in the dark when it comes to what bills lobbyists are trying to kill or pass, and how much they’re being paid for that work.

The federal government requires lobbyists in Washington, DC to file quarterly reports detailing how much they are paid for lobbying and not just which pieces of legislation they’re working on, but also which particular aspects or provisions are relevant to the lobbyist’s work.

At the state level, 28 states require either lobbyists or their employers to disclose some information about lobbyist compensation. In 15 states, lobbyists or clients must state their positions on specific bills.

Nine states require both: Alaska, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces, was the lone New Mexico lawmaker seeking similar reforms this year. His first bill would have required registered lobbyists or their employers to disclose lobbyist compensation, while the second would have required lobbyists to report which bills they had been hired to support, oppose, or otherwise worked on at least once during the session. Neither bill received a committee vote, and only the second received a hearing.

“It’s an important, very important, transparency bill that frankly unlocks some of the greatest mysteries of the legislative process,” said Steinborn during the one Senate Rules Committee hearing on the topic. Lawmakers ran out of time before they could vote on the measure, and never brought it up again.

“It’s the Senate Rules Committee that is the gateway to lobbyist reform,” said former Sen. Dede Feldman. “They are the brick wall upon which reformers hurl themselves.”

Feldman said the ongoing failure to enact reform primarily stems from the realities of New Mexico’s citizen legislature–– the last in the country to deny lawmakers a salary. Lobbyists, especially those who remain in the business over decades, provide invaluable knowledge and expertise to lawmakers even as they promote the interests of their employers.

“We have not been able to get the basic reforms that we need because lobbyists are so powerful in a citizen legislature, in which there is no personal staff, no salaries, no allowance for a policy assistant, or even a constituent services person,” Feldman said.

The resistance to more lobbying transparency is bipartisan, said Steinborn.

“It’s just a reflection of the discomfort people have of pulling back the curtain on the role of special interest on all sides of issues,” he said. “… I just think the benefits to the public and to the health of our democracy far outweigh that.”