Every ten years, the U.S. Census Bureau counts the population to determine how places have grown or shrunk, how people have moved, and how the composition of communities have changed.

The consequences are large. New political districts from the local to the national level are formed based on the census figures. Some states pick up new congressional districts. Some communities gain or lose representation in their statehouses. The head count also determines how much money a community might receive from a range of government programs.

Some say one practice of the census — counting prisoners as residents of the places they are incarcerated — results in an unfair transfer of political power away from those prisoners’ home communities. In effect, communities where prisons are located—often rural, and nationally, more white—include in their population totals prisoners who can’t vote. This results in more political power per capita for the actual residents of those districts, while the home communities of the prisoners lose political power.

Criminal justice reform advocates refer to the practice as “prison gerrymandering.”

Effects are mostly seen at the state and local level, where there can be outsized impacts, said Ginger Jackson-Gleich, policy counsel at the Prison Policy Initiative.

“So, counties, cities, school boards, any form of local government that has districts, those can be heavily skewed by prison population,” Jackson-Gleich said.

New Mexico has never adjusted the census numbers to account for prison populations in the legislative or congressional redistricting process, said Brian Sanderoff, president of Research & Polling, the firm that has helped the state Legislature draw new political boundaries for the past four decades.

It’s certainly possible that larger prison or jail populations could have an outsize effect on how districts are drawn at the local level, he said.

Throughout the country, counting prisoners as residents of prison communities has a disproportionate racial impact. In many states, political power is shifted away from communities of color and cities to rural areas with predominantly white populations.

In Illinois — which, earlier this year, became the most recent state to pass legislation against prison gerrymandering — almost half of the roughly 39,000 people incarcerated in state prisons were sentenced in Cook County, where there are no state prisons. Black people are disproportionately represented in Illinois prisons, while most prisons are in rural, white communities, according to Medill Reports Chicago.

The racial impact in New Mexico is unclear because the state doesn’t sufficiently track the race or ethnicity of prisoners. But the Prison Policy Initiative found that Native Americans and Latino and Black people are overrepresented in the state’s prisons and jails.

“It’s the use of people’s bodies who often can’t vote. It’s the use of their bodies to increase the representational strength of one group of people, and it doesn’t at all heed the interests of those people who are captive constituents,” said Samantha Osaki, an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer.

“We like to think of it as the double hit, double whammy of mass incarceration. The very first hit is the loss of physical bodies, people in those communities, and then the second hit is the loss of political power,” she said.

Also unclear is whether there’s a similar divide between urban and rural communities in New Mexico. The Corrections Department has denied New Mexico In Depth’s request for records of each inmate’s last residence and their zip codes, although a spokesperson confirmed the department has that information in individual files as well as in its centralized offender management system.

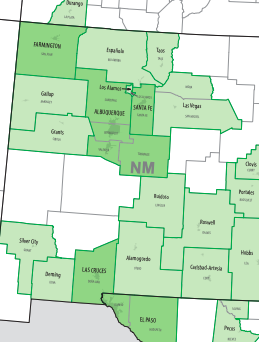

But a look at where prisons are located in the state suggests people from urban areas are being incarcerated, and counted as residents, in rural communities. While 67% of the state’s population resides in one of the seven counties that make up the state’s four metropolitan areas, just 33% of prisoners reside in the three prisons located in those counties. All other prisoners are incarcerated in eight prisons located in more rural communities.

Advocates say the Census Bureau counting prisoners at their last residence instead of the places they’re incarcerated would be the ideal solution to prison gerrymandering, but for now, it’s up to individual states to take action.

Ten states have adopted laws ending prison gerrymandering, the most recent being Illinois, where, beginning in 2030, inmates will be counted at their last residence when new districts are drawn. More than a hundred counties and cities are known to avoid the practice through methods like ignoring the prison population and splitting it equally between all districts.

With this year’s legislative session done, it appears New Mexico won’t be joining the list of states that have ended prison gerrymandering in 2021.

That leaves it up to redistricting officials, who commonly turn to attorneys general for guidance. In a letter sent to Attorney General Hector Balderas in January, Jackson-Gleich with the Prison Policy Initiative outlined measures that could be taken to avoid prison gerrymandering, and urged Balderas to support officials in taking those measures.

Sanderoff said there are incarcerated people in state prisons and local jails, as well as federal inmates in private prisons, so it would be a complicated task to actually use their home addresses in redistricting. “They would have to start a couple years ahead to develop a process for determining those addresses when the census is conducted,” he said.

Advocates say there are other ways to solve the problem. On the state level, prison populations could be divided among districts, which would mitigate the effects of prison gerrymandering. On the local level, cities and counties could entirely remove prison populations from their counts and only count true residents.

In response to an inquiry from New Mexico In Depth, a spokesperson wrote in an email that the Attorney General has “directed staff to engage stakeholders to ensure our office advises lawmakers to follow the most fair and equitable redistricting plan,” and said that plan “includes accounting for prison population adjustments.”

A bill passed during this year’s legislative session mandates the creation of an independent redistricting commission, which will draft district maps for the Legislature to consider and amend before passing to the governor for final approval.

Osaki said that although it’s unclear how much influence the commission will actually have, as the bill simply dictates that the maps drafted by the commission be presented to the Legislature for consideration, it’s still a source of hope for advocates.

“There’s going to be about a dozen public hearings, and they’ll allow for virtual participation, so that’s like a dozen opportunities to get in front of people who have some sort of power over the mapmaking process and help educate them on the issue,” Osaki said. “I think a huge hurdle for the movement to end prison gerrymandering is just a lack of interest, activism, even knowledge about the issues.”

Bella Davis is a recent graduate of the University of New Mexico and a 2020/2021 New Mexico In Depth academic fellow.