Legislative analysts have repeatedly warned since 2016 that government agencies’ increasing reliance on no-bid contracting puts New Mexico at increased risk of waste and fraud. Their most recent admonition came a month after a state grand jury indicted a former powerful lawmaker for racketeering, money laundering and kickbacks related to a no-bid contract.

Lawmakers have largely ignored those warnings; in fact, a bill pre-filed for the legislative session starting Tuesday in Santa Fe appears to create new exemptions to the procurement code. Nor is reform a high priority for Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, whose three years in office have been marked by a sharp rise in no-bid contracting.

“Such an item is not currently an element of the agenda,” said Nora Meyers Sackett, a spokeswoman for Lujan Grisham, who has the power to set this year’s 30-day legislative agenda, as lawmakers are otherwise limited to budget matters. “But the governor’s office will, as always, review and evaluate potential initiatives.”

Since 2019, Lujan Grisham’s first year in office, her administration has circumvented competitive bidding on at least 886 occasions, approving sole-source and emergency contracts worth more than $796 million, greatly outpacing her Republican predecessor, according to New Mexico In Depth’s analysis of reports from state agencies under Lujan Grisham’s control.

Such no-bid contracting is allowed under special circumstances, when services or goods are unique or needed quickly during an emergency, and Lujan Grisham’s tenure has coincided with a historic pandemic requiring quick action, a challenge Republican Gov. Susana Martinez never confronted. The biggest year for non-competitive contracting came in 2020, the year COVID-19 spread across the globe. The second largest year, 2021, wasn’t even close.

But the dramatic rise in no-bid contracting preceded the pandemic, records show.

The cost of no-bid contracts during the first year of Lujan Grisham’s leadership — $148.7 million in 2019 — was at least twice the value of such contracts for each of the six years for which New Mexico in Depth has data from Martinez’s tenure. (The state could not provide no-bid contracting details for years prior to 2013.) After peaking in 2014 at close to $60 million, no-bid spending declined during each of Martinez’s final three years in office, which roughly coincided with a state budget crisis and lean years, to just over $20 million in 2018.

While there is no evidence of malfeasance by government officials in the recent no-bid contracting spree by the Lujan Grisham administration, legislative staff have warned state lawmakers repeatedly that agencies continue to rely on emergency spending, sometimes as a result of mismanagement rather than emergencies.

The warnings take on special relevance now, with a historic infusion of money flowing through the state’s procurement system. Adding to already-swollen state coffers thanks to an oil and gas boom is an unprecedented amount of federal money through COVID relief and infrastrastructure spending.

Lujan Grisham fully supports being transparent with public money and accounting for state spending, Sackett said, adding the administration’s use of no-bid procurement is “entirely within the scope of state law,” and can increase efficiency to the benefit of New Mexicans.

But one national expert said non-competitive procurement elevates risks of waste and fraud.

“Noncompetitive procurement is the single biggest risk for fraud, waste and abuse — period,” said Tom Caulfield, a former member of the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Procurement Fraud Task Force. “The speed and agility of emergency procurement brings risk. While risks of fraud and corruption are always present in government activity, they are elevated in public procurement processes during a time of emergency.”

Normally, state agencies award contracts after a selection committee carefully reviews competitive bids or proposals. Competitive bidding is usually required for contract amounts above $60,000, to help ensure agencies hire the contractor best suited for a given task, and at the best possible price for taxpayers.

That is crucially important for earning and maintaining public trust, Caulfield said.

Not lost on longtime political observers is New Mexico’s rich history of public corruption.

Prosecutors have convicted a parade of current and former public officials for abusing the public trust over the past 20 years, including two former state treasurers, two state lawmakers, several public employees and insurance and electricity regulators. The abuse has included state procurement code violations. In 2011, a former state prisons official pleaded guilty to 30 counts of bribery stemming from no-bid roofing contracts. More recently, former New Mexico Spaceport chief financial officer Zach De Gregorio has alleged widespread corruption at that agency, including procurement code violations, in a lawsuit filed last month.

Looming most prominently over this year’s legislative session, however, is the toppling of Democrat Sheryl Williams Stapleton, formerly the second most powerful lawmaker in the state House of Representatives, for alleged corruption. The former Albuquerque Public Schools (APS) educator faces more than two dozen felony charges related to $5.36 million paid under a no-bid APS contract for vocational training services. According to the October Legislative Finance Committee staff report, the school district is among public bodies across the state that have ignored a legal requirement to disclose sole-source and emergency purchasing to the Legislature’s budget-oversight committee, the LFC, and the State Purchasing Division.

Republican state Rep. Randall Crowder of Clovis touched on the state’s checkered history in October during a legislative hearing in Santa Fe.

“In the past New Mexico has had governors and legislators that have utilized procurement to help friends, buy favor or seek contributions at a later date,” Crowder said at a Legislative Finance Committee meeting in Santa Fe. “It’s imperative that we look into this and make sure that is not going on this time.”

The risks are no secret

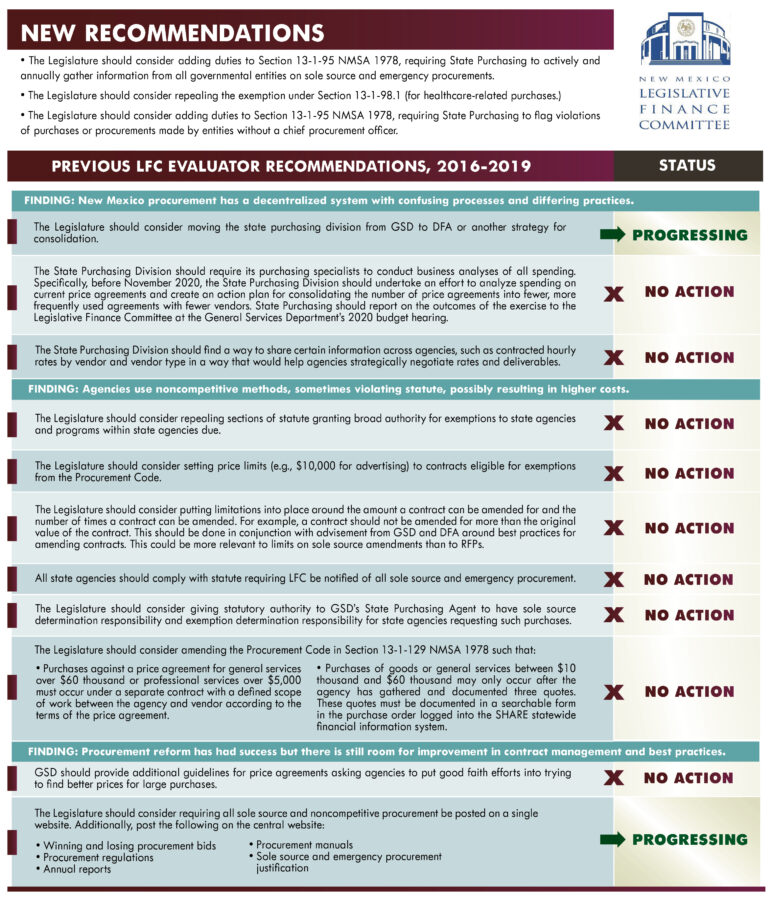

Analysts at the Legislative Finance Committee have warned lawmakers that procurement code exemptions are overused, and that state law and regulation changes are needed to better safeguard public funds. But lawmakers’ lack of action on the recommended reforms corresponds to mounting evidence of widespread departure from best practices in contracting.

In an October 2021 update to the LFC’s 2016 and 2019 evaluations of the state procurement system, LFC staff said the executive branch was not scrutinizing large purchases, and that agencies issue sole-source determinations frequently simply to buy from a vendor they prefer, instead of the contractor offering the lowest cost or best service. Agencies also sometimes award no-bid contracts simply because they’ve missed deadlines for issuing requests for proposals, they added.

Sole-source and emergency procurement are “the two most common ways that state agencies purchase goods and services without going through a competitive process or otherwise taking intentional steps to find a good deal,” LFC program evaluation manager Micaela Fischer said in an October 28 presentation to lawmakers during the hearing at the Roundhouse.

“Agencies are misusing emergency procurements, not for true emergencies that threaten the health or safety of people, as the procurement code spells out,” she said.

As the COVID pandemic barreled into the state in 2020, public officials scrambled to acquire personal protective gear and hospital equipment and to stop the spread of the virus through lockdowns, testing, and by warning people exposed to the coronavirus that they needed to get tested and self-isolate, lest they infect others.

Not surprisingly, the number of no-bid contracts skyrocketed during 2020 and 2021, the LFC reported, driven largely by COVID-related emergency procurements. But the jump in no-bid spending was already evident in 2019 (Lujan Grisham’s first year in office), New Mexico In Depth’s analysis showed.

The LFC’s October report and New Mexico In Depth’s analysis arrived at similar findings about state agencies’ increasing reliance on no-bid contracting, but the numbers differed in part because the LFC compared contracting by the state’s fiscal year, which runs from July through June. New Mexico In Depth’s analysis compared contracting by calendar years, and was limited to spending by state agencies under Lujan Grisham’s control.

The value of state agencies’ no-bid agreements in 2019 exceeded the prior administration’s in 2018 by $128.5 million, records reviewed by New Mexico In Depth showed.

That was largely due to a $108.85 million extension of the Human Services Department’s sole-source contract with Conduent State Health Care to maintain and operate the state’s Medicaid Management Information System. But even if that contract is not included, 2019 saw a near-doubling of no-bid spending from the previous year. (HSD amended Conduent’s sole-source contract yet again in 2021, for another three years, for nearly $114 million.)

Then, in 2020, as COVID-19 began to overwhelm hospitals, nursing homes and public health workers across New Mexico, the state rushed to sign hundreds of emergency contracts through the New Mexico Department of Health worth more than $309 million.

It was part of an explosion in contracting that saw state agencies sign at least 59 no-bid contracts worth $1 million or more in 2020. Several of those (worth more than $209 million combined) were issued under an umbrella authorization for COVID spending.

The unprecedented public health response won New Mexico welcome headlines. Using the state’s emergency procurement code allowed the Lujan Grisham administration to award contracts for goods and services quickly, as state agencies struggled to respond.

But it was hard to handle.

Chronically understaffed and overwhelmed by the pandemic — and the sheer number of new emergency contracts — the health department saw an “apparent breakdown of internal controls,” according to a February 2021 state auditor’s report on emergency pandemic spending.

The governor’s office stepped in numerous times in 2020 to select vendors for emergency COVID-19 contracts, without health department review, according to the auditor’s office.

Such emergency contracting allowed the administration to respond quickly, but there were consequences.

“Rushed emergency procurement led to the state being defrauded, losing millions of dollars,” Fischer, the LFC analyst, reported. She estimated the state health department was swindled out of $6.5 million by vendors awarded emergency contracts in 2020. The state prepaid for masks and other personal protective equipment, some of which never arrived.

In the February 2021 report, the state auditor’s office described those masks, destined for New Mexico’s health care facilities, as “potentially fraudulent and/or substandard.” (Because of slipshod record keeping, it’s not entirely clear where they all wound up, the health department’s own annual financial audit found.)

The COVID pandemic led to massive spending by government at all levels, and the potential for abuse was great, especially when procurement processes were bypassed.

“It is understandable that with such an intense sense of urgency, governments would place greater focus on emergency care of their citizens and less on the traditional safeguards for the prevention of corruption and fraud,” said Sheryl Goodman, a fraud examiner who served as Assistant Inspector General for the Congressionally-established Special Inspector General for Pandemic Recovery office in 2020 and 2021. (Goodman and Caulfield created Procurement Integrity Consulting Services in 2014 to advise the United Nations and governments around the world.)

“However, in doing so, they unintentionally created greater opportunities for criminal behavior, which has led, and continues to lead, to massive corruption, fraud, waste and abuse, especially against COVID relief funds,” she said in an interview with New Mexico In Depth.

Examples elsewhere around the world include fraud in contracts for vaccine distribution, and the purchase of fake vaccines, Goodman and Caulfield noted.

Despite previous warnings, the Lujan Grisham administration continued to use no-bid contracting heavily in 2021, most of it unrelated to the pandemic.

All told, pandemic response-related emergency contracting across agencies (including $3 million for vaccination incentive gift cards) represented only about 19% of no bid contracts in 2021, New Mexico In Depth’s analysis found.

Repeated, widespread violations

Sackett, the spokesperson for Lujan Grisham, said the LFC evaluation didn’t identify “any widespread abuse” of the procurement process.

Sole source and emergency procurement practices “are 100% legal processes built into state law,” she said. “If the state Legislature would like to change the processes surrounding sole-source and no-bid contracts, it is totally within their power to do that.”

Whether the abuse is widespread is open to debate, but the LFC’s October report, and previous evaluations, document repeated and widespread violations of the state procurement process. According to LFC analysts, state agencies have skirted procurement statutes and pushed millions out the door due to mismanagement.

For instance, state managers might miss deadlines to request public bids for a contract, or make other management mistakes, and simply reissue the contract to the existing vendor as an “emergency.” This practice can continue with one vendor time and time again, with costs charged to the state increasing over time, according to the LFC October report.

Such mismanagement is just one of many issues analysts have flagged in their evaluations over the years of the state’s procurement code.

They’ve also pointed to lack of transparency, failures to track spending and otherwise enforce the procurement code, and they provide evidence that state agencies have been more lenient in defining an emergency than what’s in the procurement code itself.

In addition, they submitted evidence suggesting that state agencies may be splitting projects or amending small purchases to make contracts eligible for non-competitive bidding.

“In an ideal world, all the goods and services that New Mexico government entities buy with taxpayer dollars would be competitively sourced, with vendors competing to offer the best discounts to secure the state as a customer,” Fischer wrote in her October report.

“However, as highlighted by LFC over two evaluations in the past five years,” she continued, decisions made by the State Purchasing division and state agencies not following procurement rules has led to “overspending for purchases ranging from everyday acquisitions of laptops and cars to noncompetitively sourced contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars.”

And the practice has only grown.

The following chart includes new recommendations to create more safeguards in the procurement code, that LFC analysts made in October, plus legislative progress on recommendations they made in previous evaluations. See the October report on the LFC website.

New Mexico In Depth’s Marjorie Childress and Trip Jennings contributed to this story.