Lawmakers shouldn’t read too much into the fact that New Mexico has some of the highest alcohol taxes in the country, a national expert told them today. Because “alcohol taxes across the country are very, very low.”

And Richard Auxier, Senior Policy Associate, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, gave lawmakers at the Legislature’s Revenue Stabilization & Tax Policy Committee hearing a clear answer to questions about whether raising taxes helps improve public health. Yes, he said, research shows that raising taxes reduces consumption and improves health.

In the state that leads the country in alcohol deaths, that’s important.

But when you get into the weeds of tax policy, everything becomes complicated. Lawmakers should start with understanding their ultimate goal, Auxier said.

Is it to eliminate or drastically reduce consumption of alcohol? If so, it might make sense to increase taxes significantly.

Or is it to improve public health while not making drinking alcohol so expensive that it becomes out of reach? In this case, there should be a judicious approach to raising taxes so as to not create a black market – which most know as bootlegging – or hurt small local businesses, like restaurants.

When I consider that alcohol taxes across the country are “very, very low,” it drives home that New Mexico and the rest of the country are way behind the curve when it comes to syncing up public health policy with the harm alcohol wreaks.

We called alcohol “an emergency hiding in plain sight” in Blind Drunk, our series about alcohol’s harms in New Mexico.

A reminder from the first article:

“New Mexicans die of alcohol-related causes at nearly three times the national average, higher by far than any other state. Alcohol is involved in more deaths than fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamines combined. In 2020, it killed more New Mexicans under 65 than Covid-19 did in the first year of the pandemic — all told, 1,878 people.

“This outsized harm defies easy explanation. Alcohol kills people in New Mexico at higher rates than in states that are poorer, states where more people drink, and states where the drinkers drink more. “Our risk behaviors do not line up with our deaths,” said Michael Landen, New Mexico’s State Epidemiologist from 2012 to 2020.”

We also noted, right away, that state leaders hadn’t shown much interest in tackling alcohol abuse. But the response from lawmakers since we published the series in July has been notable – at hearing after hearing over the last few months they’ve discussed what to do about the state’s alcohol crisis. This week they discussed ensuring that all revenue from alcohol taxes go to treatment, rather than some of the revenue being diverted to the state’s general fund, as a place to start.

It drives home for me that a powerful role of journalism is to make problems visible. You can’t fix what you can’t see – either because it doesn’t affect you personally, or no one at state agencies or in advocacy groups are drawing your attention to it, or it’s obscured by other problems that more readily spill into public view.

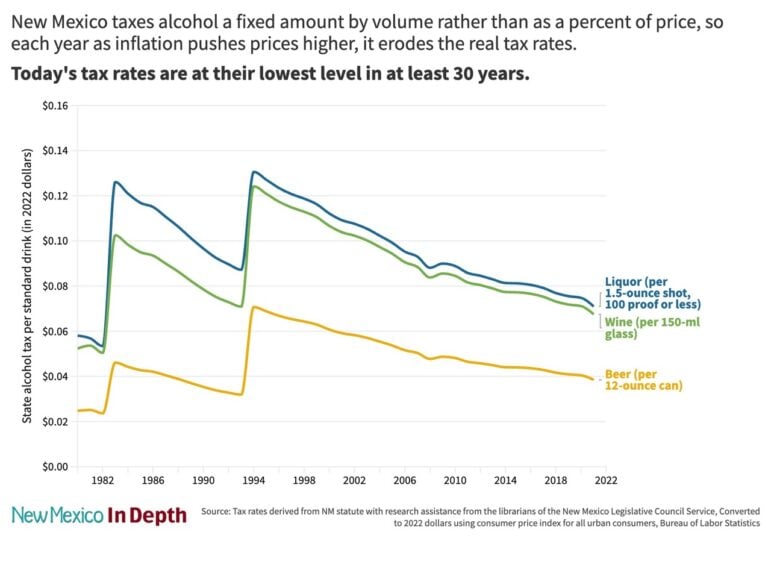

Raising taxes is one of the foremost solutions experts offered reporter Ted Alcorn when he was investigating alcohol deaths for the Blind Drunk series.

But taxes are just one tactic. Our hope is that by making the alcohol crisis more visible, it prompts a deep, wide-ranging conversation about an array of possible solutions and a deliberate, holistic response across society. Lawmakers are an important part of this process.

We devoted an entire article to how lawmakers can marshall the “whole of society” response needed. Number one on the list of solutions is, as Auxier recommended, to establish clear and measurable goals. A high-level task force to review evidence, make recommendations, and track impact over time is crucial as well.

Here’s a print-friendly version of our solutions article, A Sober Appraisal. If you find it helpful, feel free to share it with others.