Norman Norvelle’s family rolled into New Mexico’s San Juan Basin in 1957, when he was just 11, their belongings loaded into a 1953 Chevrolet sedan and an aging, half-ton pickup truck.

At the time, Farmington — the region’s largest town — still lived up to its name. “It was a beautiful place,” Norvelle said. “There was orchards and truck gardens everywhere.” Norvelle remembers driving with his family north into Colorado and up to Kennebec Pass, high in the La Plata Mountains, and gazing out across the Basin. The air was so clear then he could see the Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque, some 200 miles to the south.

It wouldn’t stay that way for long. Lying deep underneath the juniper and piñon forests, shrub-covered mesas and cottonwood studded river bottoms are vast stores of oil and natural gas, fossilized organisms that once plied the shallow inland sea that spread out across the region some 75 million years ago, and a thick bed of low sulfur coal, the leftovers of fecund and sultry shoreline swamps. Oil and gas drillers first came for the hydrocarbons in the early 1920s, but the industry really took off in 1950, when El Paso Natural Gas built a large pipeline from the San Juan Basin to California. Construction workers spilled in from all over, followed by roughnecks from Oklahoma, Texas and beyond.

Farmington’s population doubled, then tripled and before long the quiet little burg had ballooned to become the region’s population and commercial center. Well pads, processing plants, gathering systems and trailer parks sprouted where once stood orchards and melon-patches. Two giant coal power plants and their mines sprouted along either side of the San Juan River, churning out juice for hundreds of thousands of far-off homes. The community transitioned from farming and ranching to hydrocarbon extraction and combustion. While the new industry was lucrative, it was also volatile. “The Farmington economy was always oil and gas bust and boom,” said Norvelle, whose father — a diesel mechanic — had to go to Alaska for work when the local industry slumped in the 1960s. “They used to have a bumper sticker that said, ‘God, please give us one more boom and I promise not to piss it away this time.’”

And God, or rather global markets, complied, giving the region multiple booms — during which the community strained under the abundance of cash and people — and the downturns that inevitably followed — when efforts to ease the economic and societal whiplash via diversification blossomed, only to be snuffed out during the next boom. The cycle repeated for six decades.

Now, the topsy-turvy rollercoaster has been tossed off the tracks: The natural gas industry — once the region’s cash cow — is mired in a long-term slump. This summer one of the two coal plants is scheduled to shut down, taking some 400 high-wage jobs with it; the second plant is likely to follow within the decade. The region is facing down an energy and economic transition, whether it likes it or not. “Our economy has always been focused on energy,” Arvin Trujillo, who helms Four Corners Economic Development, said in a 2020 interview. “We need to look in other areas — to diversify our economy and market the quality of life.”

It sounds straightforward, but in the San Juan Basin, where fossil fuels are inextricably entangled in the economy, the culture and even the communities’ identities, it is anything but.

This article is one in a series published in late June by the Energy News Network and co-published by High Country News. Reporter Jonathan Thompson found New Mexico’s efforts to transition to a clean energy economy in the state’s northwest won’t be easy as companies make a play to keep tapping natural gas and coal through carbon capture and sequestration and a new hydrogen fuel sector. New Mexico In Depth is republishing the three-part series because global efforts to move away from fossil fuels to clean energy sources will be central to New Mexico’s economy over the coming decades.

Articles:

Will carbon capture help clean New Mexico’s power, or delay its transition?

In San Juan Basin, cultural, economic bonds slow fossil fuel transition

New Mexico’s coal transition law still faces an uncertain timeline

Smog, and stability

Shortly after the Four Corners Power Plant’s stacks began spewing a plume of unhindered carbon, sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxides in the 1960s, Norvelle’s 200-mile view vanished behind a curtain of smog. Ash piled up by the millions of tons on the banks of arroyos. Pollutants and particulates rained down on residents of nearby communities, compounding the environmental impacts of the oil and gas industry, which was already well established.

But the plants and mines also offered thousands of relatively well-paying jobs along with various revenue streams to the state, local, tribal and federal governments. More importantly, they offered a sort of stability that more lucrative oil and gas lacked, which helped grow a relatively strong middle class in the region.

As the industries increased their economic footprint in the region, state and local officials established a framework for capturing a portion of the substantial revenues that otherwise would mostly flow out of the region to corporate headquarters. Fossil fuel operations and the myriad businesses that have sprouted to support them, from fracking chemical outlets to shoe stores to car dealers, pay gross receipts taxes to the state, city and county on every sale. The businesses pay property taxes on their land, equipment and oil and gas and coal production. Producers pay severance and emergency school taxes on the gross value of oil or gas that they sell, and royalties to the federal government, the state, tribes or private landowners.

These funds, in turn, pay for everything from firefighters’ and teachers’ salaries to roads and day-to-day governmental operations. Earnings from the state’s $22 billion Land Grant Permanent Fund, which is fed almost entirely by oil and gas royalties on state lands, support New Mexico’s public schools. The San Juan plant and mine pay $3.5 million annually in property taxes to the 3,000-square-mile Central Consolidated School District that reaches deep into the Navajo Nation, according to a 2019 study by O’Donnell Economics and Strategy, and nearly $2 million to the community college. The mine is one of the largest customers of several local businesses, forking out millions of dollars per year for everything from porta-potty rentals and environmental studies to fuel and electricity.

More than a couple of degrees of separation from the industries is rare. Norvelle — now an active member of the environmental community — worked as a construction laborer on the Four Corners plant, then as a fuel and water analyst at the San Juan station, and later as a chemist for El Paso Natural Gas. Trujillo, the economic developer, worked at the coal mines and the Four Corners Power Plant and his organization’s board and membership rosters are stocked with fossil fuel industry officials and companies. Energy companies sponsor the local symphony and sports events and give thousands of dollars annually to scholarship funds. The local baseball team was named the Frackers.

It’s all so tangled that the community can feel like an extension of the industry. Efforts to rein in industry, mitigate pollution, or even diversify or transition the economy are therefore perceived as an attack on the community. In recent months, for example, the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association has launched a campaign portraying efforts to slow drilling as anti-public education.

This quasi-symbiotic relationship meant that, in the early 2000s, when the fossil-fueled economy was firing on all cylinders, the community’s economy thrived. Natural gas prices shot up to record highs, spurring a drilling boom. Construction of a third coal-power plant in the region, Desert Rock, was proposed in 2003 to help meet burgeoning demand for electricity. Federal royalties from wells in the San Juan Basin topped $700 million in 2007, and state severance tax revenues were close to $1 billion. Schools got a per-pupil funding increase, allowing the Farmington district to hire more teachers and up their salaries, and new construction could barely keep up with population growth. It seemed as if it would go on forever.

“People say we should have done this stuff [diversify the economy] years ago. We didn’t. I was caught up in it too,” said Trujillo, who was the executive director of the Navajo Nation Division of Natural Resources during that time, and a proponent of Desert Rock. “You would look at it all and say, ‘The plants won’t shut down … we’re doing fine. If it’s not broke, why try to fix it?’”

That all changed in late 2008, however, when abundant natural gas supplies from the Bakken and Marcellus shale formations glutted the market, causing prices to crash. Between October 2008 and January 2009, Aztec Well — the region’s largest locally owned oilfield services company — idled 75% of its equipment, and almost as many workers, according to Executive Vice President Jason Sandel. ConocoPhillips, WPX and BP sold their assets to smaller, private equity-backed companies and fled, taking with them the high-level management jobs, salaries and, in many cases, their philanthropy and community involvement.

The San Juan Basin lost an estimated 5,000 jobs and tax revenues plummeted. Low natural gas prices hit coal, too. The Desert Rock proposal — battered by tenacious local opposition — unraveled in 2009. Environmentalist lawsuits and divestment by California utilities forced both Four Corners and San Juan to shut down generating units and install costly pollution-control equipment in 2014 and 2016, respectively. The mines’ owner BHP Billiton bailed, leaving the Navajo coal mine to the Navajo Transitional Energy Company — a tribe owned entity — and the San Juan mine to Westmoreland, which entered bankruptcy in 2018.

And then, in 2017, the bombshell: San Juan Generating Station would close in 2022 and Four Corners Power Plant was imperiled, too.

Diversification gets a jolt

When it became clear that the natural gas industry would not rebound, T. Greg Merrion, then-president of a local family-owned oil and gas company, got together with other community leaders to try to fix the now broken economy. They hired a consultant, who told them they needed to diversify, branch out into agriculture and tourism, and court light manufacturers and healthcare providers. To help do this, they formed Four Corners Economic Development, a private nonprofit.

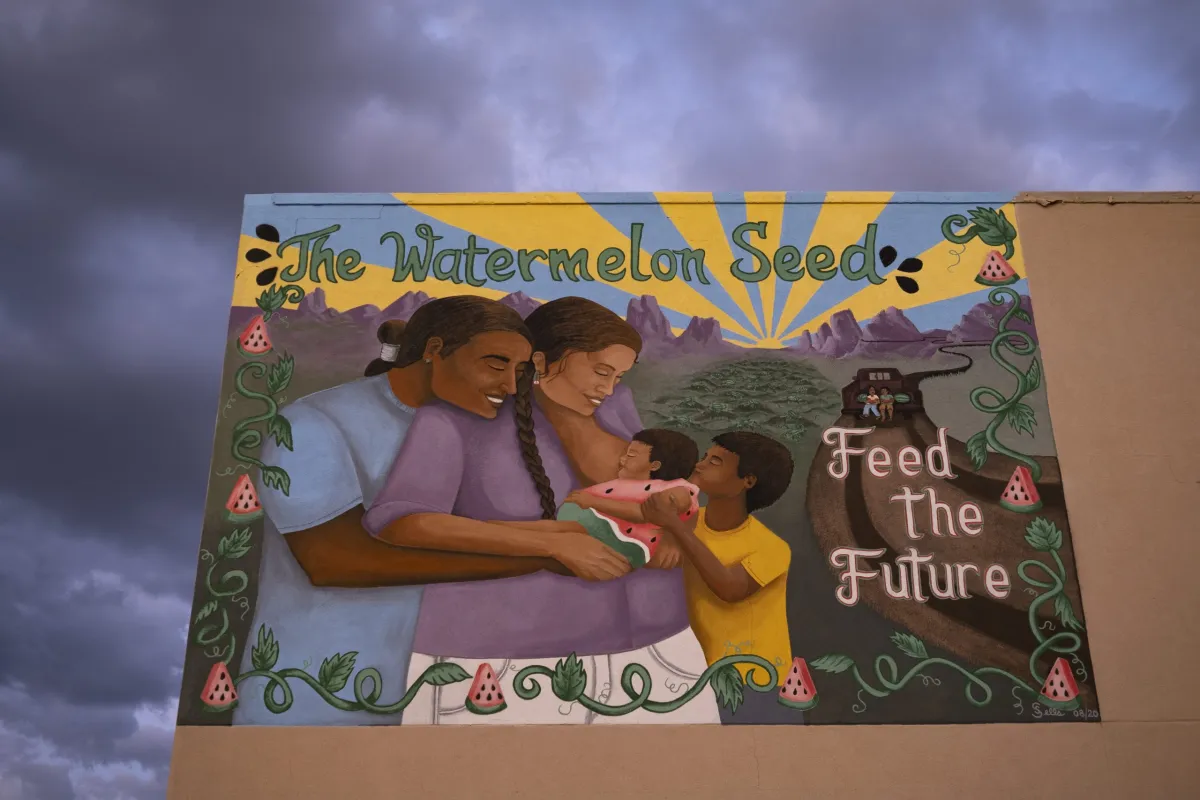

The organization, together with local governments, has made strides toward diversification. The local visitor’s bureau in 2015 launched a “Jolt Your Journey” branding campaign aimed at emphasizing recreational opportunities and wiping away the “national sacrifice zone” stigma long attached to the region. The city implemented an economic development sales tax, created an economic development department, added recreational amenities to the town reservoir, increased marketing of tourist attractions, and recently finished the first phase of a “complete streets” overhaul of the downtown, making it more amenable to pedestrians and small businesses. FCED has supported the Harvest Food Hub that links farmers up with local restaurants and retail outlets, and backs initiatives to lure the outdoor recreation and film industries to town.

Revitalization efforts have helped bring Farmington’s historic downtown district back to life with improved sidewalks, roundabouts, new restaurants, culturally relevant businesses and public art projects. Credit: Jeremy Wade Shockley for the Energy News Network.

Renewable energy developers are moving in, as well. Photosol, a subsidiary of a French renewable energy company (and one of FCED’s only non-fossil fuel energy industry members), has proposed three utility-scale solar projects for the area, one on Bureau of Land Management land and another on a private parcel near San Juan Generating Station, enabling them to tap into existing transmission lines, and another on old workings of the Navajo Mine near the Four Corners plant. Two pumped hydropower storage projects are in the conceptual phase of development.

So when Farmington Mayor Nate Duckett dons Lycra and hops on a mountain bike to promote the area’s recreational opportunities, it may appear as if the region is genuinely transitioning its fossil fuel-saturated economy. But he and other leaders are clear that they intend to develop these additional layers of the economy “in conjunction with, rather than instead of” fossil fuels, as Farmington’s economic development director put it.

A similar dynamic plays out at the state level. Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham was instrumental in passing the Energy Transition Act and has enacted new regulations on methane emissions from oil and gas facilities. At the same time, she has pushed hard to establish a “clean” hydrogen hub in the state, an effort that dovetails with FCED’s attempt to lure petrochemical manufacturing to the region with its abundant natural gas and energy infrastructure. Lujan Grisham supports her efforts with a study touting blue hydrogen — which uses methane or natural gas as a feedstock — authored by New Mexico Energy Prosperity, which shares an address with Aztec Well. Sandel, the executive of the company and a long-time advocate of the “in addition to” form of economic diversification, has supported and contributed to Lujan Grisham’s campaigns. He also sits on the Energy Transition Act’s citizens advisory board.

Oil and gas dollars have paid for the modern, sleek facilities of the San Juan College School of Energy. The state gave the school $500,000 a few years ago to develop a renewable energy center. But the “Center for Excellence” curriculum — with hydrogen, electric vehicle and lithium battery programs, but no wind or solar — is still under development. The school offers degrees in petroleum production management, energy production foundations (focused on natural gas), natural gas compression and tribal energy management. It used to have renewable energy classes, too, but college officials say they were dropped due to lack of interest. Now “solar” does not appear in the school’s course offerings except as part of the astronomy class. And, instead of training power plant workers to build the proposed solar installations, the college is partnering with Enchant Energy to equip the workers to run a plant with carbon capture, regardless of the scheme’s uncertain future.

Irreplaceable wages

Duckett, meanwhile, is one of the most ardent boosters of Enchant Energy’s bid to keep San Juan Generating Station open — with or without carbon capture. He explained why on his Mayor’s Table video podcast late last year: “Energy is key. When we’re talking about retraining a workforce: What are you going to retrain them to do that allows them to make the kind of money they’re making right now in the coal mine? It doesn’t exist.” A 2019 report on energy transitions from the Western Rural Communities Program found that San Juan Basin fossil fuel workers earned nearly three times as much as their counterparts in other industries.

“These jobs with the fossil fuel industry are irreplaceable,” admitted Mike Eisenfeld, energy and climate director for the San Juan Citizens Alliance, a local environmental group. “I don’t make $80,000 per year. That kind of salary is what happens when they don’t have to deal with externalities.”

Each of the proposed solar plants would employ up to 500 people during the construction phase, the developers say, and a 2019 study found that a utility scale solar facility could fill in most of the property tax void left by the coal plant’s departure. But once the solar plants are operating they’d only require a dozen or so full-time workers making less than coal miners.

“Wage differentials are a significant deterrent to change,” the energy transition report’s authors write. “Many workers are unwilling or unable to accept lower wages, even when they can find alternative work or access skills training. Instead, they choose to drop out of the labor force, commute long distance to other energy locations or simply leave.”

So leaders and economic development officials turn to an all-of-the-above strategy, in which they try to diversify away from fossil fuels even as they embrace the oil and gas and coal industries. This not only spreads limited resources thin, the energy transition report notes, but it can also work at cross-purposes. Retirees drawn to the area’s climate and clean air may not want to settle downwind from a petrochemical factory. Mountain bikers may be less than eager to ride trails that wind between hydrogen sulfide-oozing oil and gas wells. Fish-consumption advisories have long been in effect in lakes downwind from the power plants due to high mercury content, and the American Lung Association recently gave San Juan County a flunking grade due to high ozone levels.

“I understand the instinct to stick with what you have,” said Camilla Feibelman, director of the Sierra Club’s Rio Grande chapter, “but economic success is always paired with diversification, innovation and creativity, not clinging to the past.”

More importantly, it slows the fight against climate change and for environmental justice

“We’re in a time now when we really need to think about the climate crisis we’re in,” said Robyn Jackson, the interim executive director of Diné CARE. “Prolonged drought, aridification of the soil, intense wind and dust storms, forest fires throughout the southwest. We have to think about some other form of economic development that isn’t based on resource extraction that sacrifices our land and people.”