When COVID-19 locked the world down in March 2020, I needed a creative outlet to help cope with the isolation. Fashion has always been how I express myself, but shopping online wasn’t the same as trying clothes on in a store. So I saved up money, bought a sewing machine, and began making my own clothes.

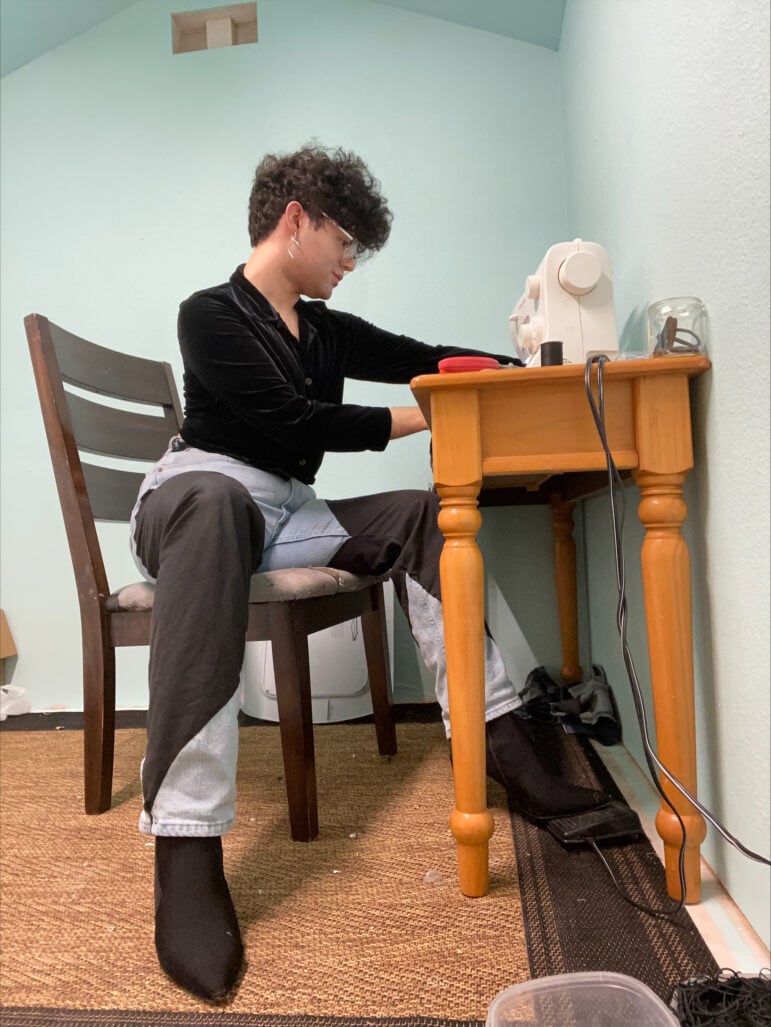

Joey Wagner works on a new piece at home, wearing clothes made from a thrifted clothing: A size 3X dress turned into a fitted shirt, and thrifted jeans with added black cutouts.

I’ve yet to stop, having discovered a new relationship with clothes that has transformed how I see fashion. And I’ve come to realize that in making my own clothes I’m also directly participating in a global conversation about the adverse effects of what some call “fast fashion.”

Fast fashion is a global business model where high fashion runway looks and trendy styles are quickly replicated in factories and then shipped to consumers across the globe. Social media, in particular, fuels constant consumption of cheaply made clothes that someone might wear just one or two times before moving on to the next clothing trend. The negative environmental and social impacts are astounding.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the fashion industry each year uses 93 billion cubic meters of water (which translates to about 24 trillion cubic gallons), enough to meet the needs of five million people.

The global agency estimates that 10% of global carbon emissions come from the fashion industry, more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined. One reason for that is the global nature of the industry: clothes made in low-wage factories and shipped to higher wealth countries.

Then there’s other pollution. Almost 90% of the fiber used in clothing ends up incinerated or in a landfill. Twenty percent of wastewater worldwide comes from fabric dying and treatment, and half a million tons of plastic microfibers enter the ocean, which UNEP estimates to be about the same as 50 billion plastic bottles.

Another major concern with fast fashion is the treatment of factory workers. Not only are they underpaid, but they’re producing clothes on their feet for long hours.

For creative people for whom fashion is important, how to act responsibly can overwhelm. The problem is big and it requires big solutions. But a constellation of options are available to us, I’ve realized, to engage in what some refer to as “slow fashion.”

We can wear the clothes we buy more often, over a longer period of time. We can mend and care for our clothes to sustain their life span. We can purchase locally or regionally produced clothes that might cost more but also would likely be more durable. Or, we can purchase used clothing from second-hand vintage and thrift stores and turn them into our own new creations.

Repurposing secondhand clothing is easier than you might think. Most towns have thrift stores offering up another person’s unwanted clothing. And larger cities, like Albuquerque where I live, have local shops that specialize in vintage clothes, older pieces that are often better made than what you find today in the big retail stores or online.

“I think, personally, the overall quality of the clothing pieces…a lot of these [pieces] have been handmade, it’s just simply a lot better, and I mean, that’s why they’re still around,” said Carlos Vargas, one of the owners of Avengers Vintage, a vintage clothing store in Albuquerque.

Vargas is one of several local owners of shops I frequent. He said the quality difference between older clothing and what can be found these days online becomes obvious the more we really look. “…try things on, feel the fabric, look at the way the piece is made, really pay attention to the details …you will really start to realize in the details how much more well-made it is.”

Some local stores have begun incorporating vintage clothing to respond the fast fashion environmental problems. Andy and Edie, a local boutique “where art meets fashion” in Albuquerque, carries both new and vintage clothing, including independent designers and brands.

Store manager Amanda Cardona said a primary goal is to provide affordable, on trend clothes that aren’t necessarily what one would find at the mall. But critiques of the fashion industry have had an impact. “As we started learning just how damaging it is, in the numerous ways it is, that’s when we started to shift,” Cardona said. “I’ve been here for four years now and where we source things has evolved in that time, not simply because of me, but just the conversations we have with the people directly, in this community.”

Vintage stores, boutiques, resale shops and thrift stores are the places I’ve relied on in my own sewing journey. I immersed myself into making my own clothes with the mindset of “screw it, I’ll do it myself.” I am entirely self-taught, which means I improved through a lot of trial and error (emphasis on error).

I started off by upcycling or altering clothes I purchased from thrift stores to more align with my style. This is not to say that this is the only way to begin sewing clothes, many classes are offered online or in person at different fabric stores. You may even be lucky enough to know someone who already sews.

But I’m living proof that any person can make their own clothes. I knew nothing about sewing before the pandemic and I’ve discovered many of the benefits. Mainly, I’m able to curate and develop my own personal style, with full control over the finished product.

Since I’m a man, making my own clothes has also helped me respond to a fashion landscape that doesn’t generally provide the style of clothing I prefer, in my size. My clothes fit better and I’m able to stay up on recent trends while being unique and environmentally conscious.

And since starting to produce my own clothing two years ago, I have not bought a single clothing item from a fast fashion retailer.