The push to change the state’s taxes on alcohol all but ended Friday when the House Taxation & Revenue Committee voted down one bill and declined to take action on another. Chairman Rep. Derrick Lente, D-Sandia Pueblo, encouraged the bills’ sponsors to re-work their proposals in the coming months. But with no other measures advancing to address the state’s worst-in-the-nation rate of alcohol-related deaths, the Legislature kicked the can down the road on one of the state’s leading public health crises. Unlike last year, when an effort to raise alcohol taxes provoked vociferous opposition by beverage makers and retailers, dooming the proposal, the most important fissure this year was within the group supporting changes in alcohol taxes. In deliberations that stretched over two days, the tax committee considered divergent proposals.

Alcohol

Lujan Grisham axes tax increase on booze

|

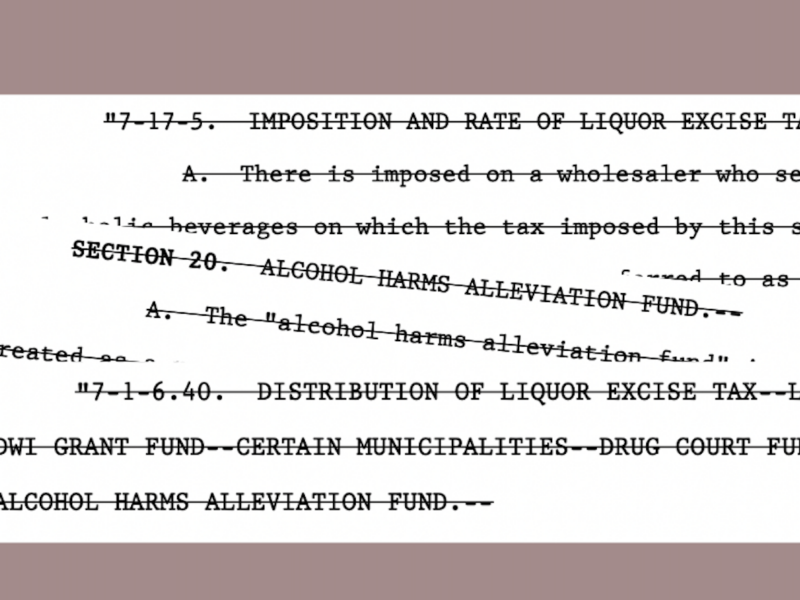

Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham on Friday struck down the first alcohol tax increase in 30 years meant to address a public health crisis that claims thousands of New Mexican lives a year.Lujan Grisham’s veto came as a surprise to state lawmakers. During weeks of negotiations with the governor’s office and each other during the legislative session, lawmakers had shaped a $1.1 billion tax package only to learn that she had liberally crossed through line after line in the 119-page bill.The decision to eliminate the alcohol tax, in particular, contradicted the rhetoric coming out of the governor’s office this week leading up to the vetoes.

Lujan Grisham sounded the alarm about the potential for the tax package to undermine the state’s long-term financial health. The proposed tax cuts represented future dollars the state would not collect, which some pointed to as a risk given the state’s volatile revenue stream. New Mexico is overly dependent on the boom and bust cycles of the oil and gas industry.However, the nominal increase to the state alcohol excise tax — less than 1 cent on a 12 ounce beer and about one and a half cents per servings of wine and liquor — would have generated roughly $10 million a year.

The tax bill would have directed those dollars as well as about $25 million in money that currently goes to the state’s general fund to a new Alcohol Harms Alleviation fund for treatment.

Unclear is why the governor didn’t eliminate the harm alleviation fund in the tax bill, while keeping the tax increase, given her concerns over shoring up the state’s revenues.

Among those stunned by the governor’s decision Friday was Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, D-Albuquerque, a co-sponsor of the proposal to increase the state alcohol tax.“I would expect an increase in alcohol excise tax would be welcome in light of the harm to the communities and cost to the state due to alcohol,” Sedillo Lopez said Friday afternoon.Maddy Hayden, the governor’s spokeswoman, declined to say why Lujan Grisham had vetoed the alcohol excise tax increase when it would have put dollars into New Mexico’s coffers.She did say, however, “The governor spoke at length to the media (Friday) about the continued need for dedicated resources to address alcohol misuse. As you know, she recommended creating an office at the Department of Health dedicated to alcohol misuse and the budget as signed includes $2 million for that purpose.”Hayden was referring to a Friday afternoon press conference Lujan Grisham held in Santa Fe.In 2021, alcohol killed 2,274 New Mexicans in 2021, at a rate no other state comes close to touching.

Alcohol

How a 25¢-per-drink alcohol tax fell apart

|

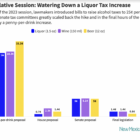

The Santa Fe New Mexican chronicled how efforts to increase taxes on alcohol over the past 30 years have hit a brick wall at the Roundhouse. Lawmakers budged in 2023, raising the tax per drink by a penny — far short of a 25 cent proposal. Illustration by Marjorie Childress. Ever seen someone make a quarter disappear? You did if you watched this year’s legislative session, where advocates seeking to stem the state’s tide of alcohol-related deaths proposed a 25¢-per-drink tax — and lawmakers shrank it down to hardly a penny.

Alcohol

Lawmakers water down alcohol proposals amid public health crisis

|

ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO – JUNE 26, 2022: The alcohol department at a grocery store Albuquerque, NM on June 26, 2022. CREDIT: Adria Malcolm for New Mexico In Depth

The alcohol industry notched a victory Saturday as the Legislature approved an alcohol tax hike of less than a penny-a-drink on beer and hardly more than that for liquor and wine, a fraction of the 18- to 20-cents public health advocates pushed for in this year’s session.

Lawmakers also rejected a $5 million request from the Department of Health for a new Office of Alcohol Prevention, despite the state’s historic budget surplus. A DOH spokesperson said its epidemiology division would create a smaller version of the office anyway, using an additional $2 million lawmakers added to the agency’s budget.

Public health experts say the tax increase is so small that it’s unlikely to have any effect on excess drinking, let alone tackle New Mexico’s worst–in-the-nation rate of alcohol-related deaths. The chair of the House tax committee, Rep. Derrick Lente, D-Sandia Pueblo, who had rejected a compromise 5¢-per-drink proposal passed by his counterparts in the Senate, acknowledged the final increase was minor on the floor of the House of Representatives on Saturday morning. “If we want to call it minimal, we can call it minimal,” he said.

2023 legislative session

Senate committee passes nickel-per-drink increase in alcohol taxes

|

On Wednesday, a Senate committee amended a tax package passed by the House earlier this week to hike alcohol taxes 5¢ per drink for beer, wine, and spirits, greater than the 1¢ to 2¢ increase included in the original proposal. The hike, larger than opponents had wanted but smaller than supporters had hoped for, would be the first in 30 years.

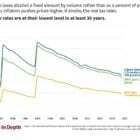

Research has shown that making alcohol costlier is a way to reduce excess drinking, and supporters argued that a significant tax increase is necessary to combat the state’s alcohol crisis. New Mexicans die of alcohol-related causes at nearly three times the national rate and alcohol is involved in more than twice the deaths statewide as are fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamines combined. New Mexico’s alcohol taxes do not adjust with inflation and have lost much of their real value since lawmakers last raised them. The 5¢ increase, approved by the Senate Tax, Business and Transportation committee, would bring taxes on wine and spirits back to the real value they had in 2000.

2023 legislative session

House committee cuts proposed alcohol tax increases

|

A nearly $1 billion tax package cleared the House Taxation and Revenue Committee on Monday with 1-cent to 2-cent tax per drink increases on beer, wine and liquor instead of much larger rate hikes sought by advocates.Rep. Joanne Ferrary, D-Las Cruces, said following the committee’s nine-to-five vote to approve the bill that supporters hope to amend a 15-cent per alcoholic drink increase into the legislation as it moves through the Legislature over the final two weeks of the legislative session.“We need lots of people to support that,” said Ferrary, one of the sponsors of House Bill 230, which would have imposed a flat 25-cent tax on alcoholic drinks and would have pushed the cost of most beer, wine and liquor up by 18 to 21 cents.Supporters of raising the state alcohol excise tax have pointed to research that shows higher alcohol prices curb cirrhosis deaths, drunk driving, violence and crime, and even sexually transmitted disease. New Mexicans die of alcohol-related causes at nearly three times the national average and alcohol is involved in more deaths than fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamines combined.Even with the 1-cent to 2-cent tax increases on alcoholic drinks, industry lobbyists turned out Monday to oppose the alcohol excise tax provision in the omnibus bill. Jimmy Bates of Premium Beverage Distributing Co. a wholesaler for Anheuser Busch, said the provision would raise the cost of liquor by a smaller rate than beer.

“You have the lowest ABV (alcohol by volume) alcohol product taking a 37 percent increase and the highest in hard liquor taking a nine percent increase,” Bates said. “You’re going to drive consumers away from four to five percent ABV beverage into a 40-percent one.”

Currently, state law taxes most beer at 4 cents per drink versus 7 cents for liquor. In 2017, when a similar bill appeared before the Legislature, Bates told state lawmakers he would oppose any tax increase, however small.

Alcohol

Do alcohol taxes hurt poor people?

|

Illustration by Shelby Criswell

A bill that would raise state alcohol taxes for the first time in 30 years is in the hands of Democrats, who have a firm hold on both legislative chambers. But a major obstacle to passing the legislation is the concern voiced by some of their members about how an alcohol tax hike would affect low-income New Mexicans.

In an interim legislative meeting In October, Rep. Susan Herrera, a Democrat whose district in northern New Mexico has a higher share of residents in poverty than the state, said she refers to levies on alcohol and tobacco as ‘poor man’s taxes’ rather than as ‘sin taxes’.

“Not that I think poor people sin more than rich people,” she said, prompting laughter from her colleagues, “I just think they pay more for their sins.”

Paul Gessing, president of the local free market think tank The Rio Grande Foundation, testified to lawmakers that a tax on alcohol is regressive. Business interests and conservatives are making the argument, too. On Monday as the House Taxation and Revenue Committee discussed House Bill 230, which would raise state alcohol taxes to a quarter a drink, Sam DeWitt of the national Brewers Association tarred the proposal as “regressive.” So did Paul Gessing, president of the local free market think tank The Rio Grande Foundation, and Adam Hoffer of the Washington, D.C.-based Tax Foundation.

Sen. Antoinette Sedillo-Lopez, a Democrat representing the south side of Albuquerque who is sponsoring companion legislation, insisted the measure is meant to improve the health of lower-income New Mexicans, not to impoverish them. “This bill is about changing behavior.”

Alcohol taxes are regressive by definition, according to former state tax policy director Kelly O’Donnell, at least from a technical standpoint.

2023 legislative session

Lawmakers tackle raising the alcohol tax

|

A bill to impose a 25-cent tax on alcoholic drinks goes before its first legislative hearing of the session Friday. Looming over it is the 2017 defeat of a similar bill by the alcohol industry.Much has changed in six years. The mood of the Legislature appears different in 2023. Greater awareness of alcohol’s harms seems to have permeated the legislative body. Partly because the stats are so stark.

Alcohol

Deaths due to drinking rose sharply in 2021

|

More than 2,200 New Mexicans died of alcohol-related causes in 2021, according to new estimates from the Department of Health, capping a decade in which such fatalities nearly doubled and setting a new high-water mark in a state already beset by the worst drinking crisis in the nation. The updated data arrive as lawmakers draft legislation to reduce alcohol’s harms for the upcoming session.

Laura Tomedi, an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico College of Population Health, drew on the data at a late-November hearing of the interim Legislative Health and Human Services Committee. Tomedi, who from 2013 to 2018 led the health department’s substance abuse epidemiology section and served as its alcohol epidemiologist, told lawmakers the state’s death rate had been “going up and up and up” for years. But she described the latest trends — a 17% uptick in 2020 and another 13% jump in 2021 — as a “concerning, sharp increase.”

This spike in deaths coincided with the pandemic, she said, when “early indications are showing that alcohol use increased quite a bit.”

The mortality data, which are the most comprehensive estimates of alcohol’s full impact on New Mexicans’ health, account for all causes of death brought on by drinking including injuries in motor-vehicle crashes and violence in which the victim was intoxicated, and illnesses such as liver disease and cancer. Illness deaths due to chronic drinking made up a growing share of alcohol-attributable deaths, accounting for 62% in 2021, compared to 38% resulting from acute intoxication such as injuries and poisonings.

Alcohol

Alcohol taxes across country are “very, very low”

|

Lawmakers shouldn’t read too much into the fact that New Mexico has some of the highest alcohol taxes in the country, a national expert told them today. Because “alcohol taxes across the country are very, very low.”And Richard Auxier, Senior Policy Associate, Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, gave lawmakers at the Legislature’s Revenue Stabilization & Tax Policy Committee hearing a clear answer to questions about whether raising taxes helps improve public health. Yes, he said, research shows that raising taxes reduces consumption and improves health. In the state that leads the country in alcohol deaths, that’s important. But when you get into the weeds of tax policy, everything becomes complicated. Lawmakers should start with understanding their ultimate goal, Auxier said. Is it to eliminate or drastically reduce consumption of alcohol? If so, it might make sense to increase taxes significantly. Or is it to improve public health while not making drinking alcohol so expensive that it becomes out of reach?

Alcohol

Legislators consider key questions on alcohol tax reforms

|

Lawmakers concerned about New Mexico’s worst-in-the-nation rate of alcohol-related deaths are focused on revising how the state taxes alcohol. Last month, the Legislative Health & Human Services Committee chose an alcohol tax increase as one of its top priorities for 2023 and next week, another committee will hear tax experts present on the topic. Several top lawmakers agree the state’s alcohol taxes should be higher but they don’t know how much to increase them, whether to change how the taxes are levied, and what to do with the revenues raised. “Everyone needs to understand the landscape before we have a serious conversation about how it should be changed,” said Rep. Christine Chandler, D-Los Alamos, who chairs the Revenue Stabilization and Tax Policy Committee that meets next Thursday and Friday. Like many states, New Mexico taxes alcohol wholesalers a fixed amount per volume of beverage they sell to retailers, who raise prices on consumers to cover the upcharge.