There’s a tale of two cities unfolding in eastern New Mexico: Clovis and Portales both rely on a single source of potable water, the Ogallala Aquifer. That aquifer is finite and rapidly depleting. Five years ago, New Mexico Tech offered both communities aquifer mapping research to predict how long their reserves might last. That research guided Clovis to shutting off 51 irrigation wells and saving 4 billion gallons of water. Portales didn’t choose to use it.

Environment

New Mexico’s coal transition law still faces an uncertain timeline

|

The coal-fired San Juan Generating Station in northwestern New Mexico. Credit: Jeremy Wade Shockley / for the Energy News Network

New Mexico was on track to become a model for phasing out coal power without abandoning those who have worked, lived, or breathed under its smokestacks. The state’s largest utility had already announced plans to divest from coal. A new state law would hold it to that pledge while also providing millions of dollars in funding for workers and affected communities. “This is a really big deal,” Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said at the bill signing. “The Energy Transition Act fundamentally changes the dynamic in New Mexico.”

The 2019 law has withstood political and legal challenges, but three years later it still faces a major test.

In San Juan Basin, cultural, economic bonds slow fossil fuel transition

|

Farmington, New Mexico, is a city tied to its boom-and-bust economy, where commerce and industry take a prominant place in the urban landscape. Credit: Jeremy Wade Shockley / for the Energy News Network

Norman Norvelle’s family rolled into New Mexico’s San Juan Basin in 1957, when he was just 11, their belongings loaded into a 1953 Chevrolet sedan and an aging, half-ton pickup truck.

At the time, Farmington — the region’s largest town — still lived up to its name. “It was a beautiful place,” Norvelle said. “There was orchards and truck gardens everywhere.” Norvelle remembers driving with his family north into Colorado and up to Kennebec Pass, high in the La Plata Mountains, and gazing out across the Basin. The air was so clear then he could see the Sandia Mountains near Albuquerque, some 200 miles to the south.

It wouldn’t stay that way for long. Lying deep underneath the juniper and piñon forests, shrub-covered mesas and cottonwood studded river bottoms are vast stores of oil and natural gas, fossilized organisms that once plied the shallow inland sea that spread out across the region some 75 million years ago, and a thick bed of low sulfur coal, the leftovers of fecund and sultry shoreline swamps.

From our blog

The toxic legacy of uranium mining in New Mexico

|

ProPublica, a national news organization, published A Uranium Ghost Town in the Making yesterday, about an important topic many Americans, including New Mexicans, still know little about: the legacy of uranium in our state and the greater Southwest. The story focuses on the residents of the small northwest New Mexico communities of Murray Acres and Broadview Acres, near Grants, who continue to suffer the potential effects of a uranium mill operated by Homestake Mining of California. Those include decades of sickness, including thyroid disease and lung and breast cancer. Homestake processed ore from a nearby mine beginning in the 1950s in an area known as the Grants Mineral Belt, a rich deposit of uranium ore that runs through the northwest corner of New Mexico. Nearly half of the uranium supply used by the United States for nuclear weapons in the Cold War came from the region.

Commentary

Resisting fast fashion

|

When COVID-19 locked the world down in March 2020, I needed a creative outlet to help cope with the isolation. Fashion has always been how I express myself, but shopping online wasn’t the same as trying clothes on in a store. So I saved up money, bought a sewing machine, and began making my own clothes.

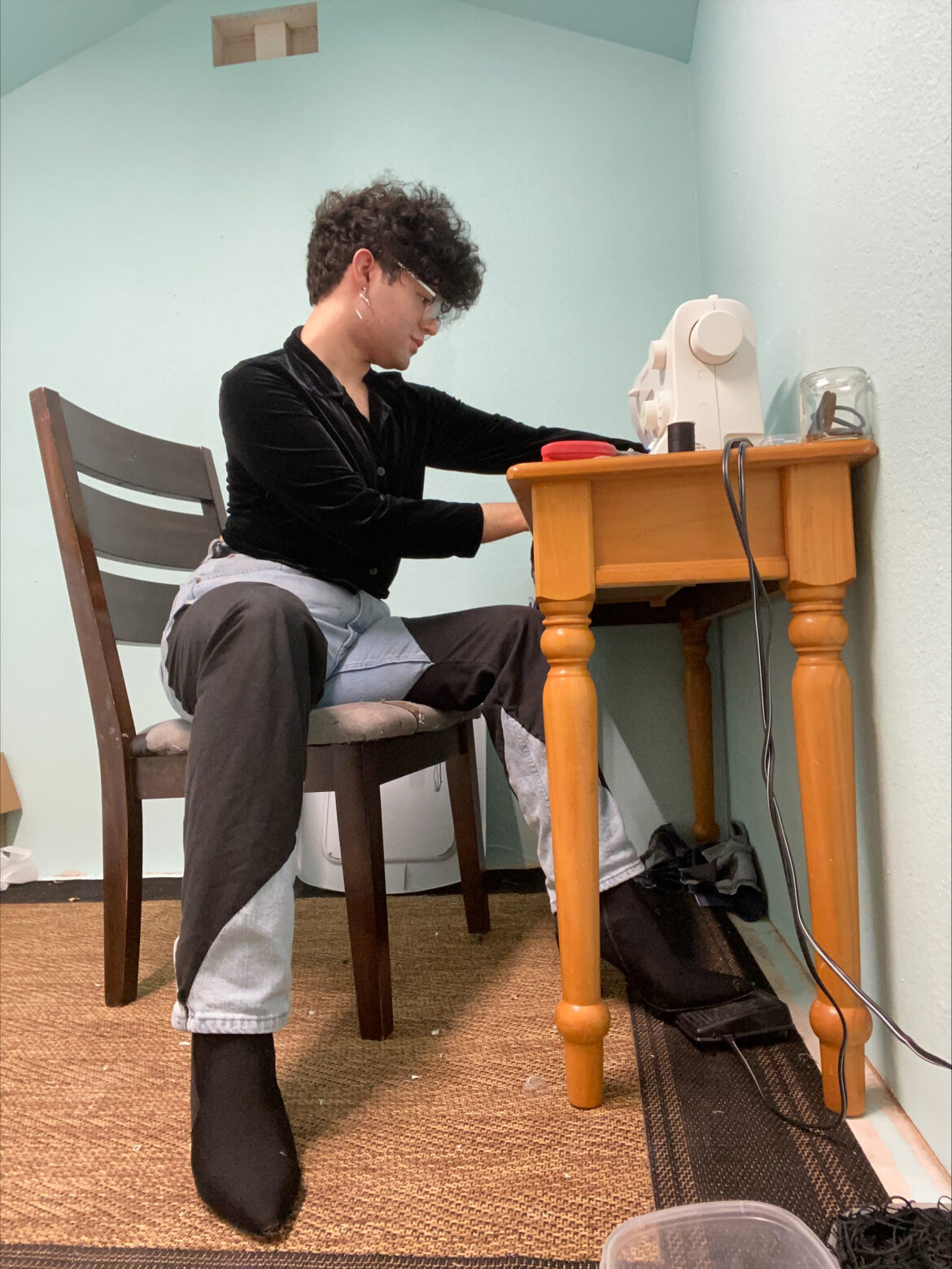

Joey Wagner works on a new piece at home, wearing clothes made from a thrifted clothing: A size 3X dress turned into a fitted shirt, and thrifted jeans with added black cutouts. I’ve yet to stop, having discovered a new relationship with clothes that has transformed how I see fashion. And I’ve come to realize that in making my own clothes I’m also directly participating in a global conversation about the adverse effects of what some call “fast fashion.”

Fast fashion is a global business model where high fashion runway looks and trendy styles are quickly replicated in factories and then shipped to consumers across the globe. Social media, in particular, fuels constant consumption of cheaply made clothes that someone might wear just one or two times before moving on to the next clothing trend.

Abandoned uranium mines

Nuclear Regulatory Commission slows decision about Church Rock uranium cleanup

|

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission appears to have slowed its timeline for deciding whether to let another federal agency house uranium-contaminated debris on a mill site it regulates near Church Rock. Local Navajo people and Navajo Nation officials object to the plan, saying the proposal doesn’t move debris far enough away from the community.

“It’s very surprising to me, in a good way,” Eric Jantz, an attorney for the New Mexico Environmental Law Center, said Thursday of the slow down in the commission’s approval process contained in a May 4 letter.

“Typically, the NRC sits back and waits for formal appeals, but this time they got involved at a critical juncture,” said Jantz, who represents the Red Water Pond Road Association, an organization formed by residents who live near two large abandoned mines and the mill site just north of Church Rock. The center has litigated on behalf of the community for decades to force cleanup of abandoned uranium waste and to resist future uranium mining.

The slow down by the commission follows a historic visit in April that NRC commissioners made to the Red Water Pond Road community, about 20 minutes northeast of Gallup. The commissioners wanted to see the mine and mill sites for themselves, and to hear what residents and Navajo officials, including Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez, thought.

The EPA plan to move the uranium contaminated mine debris to the mill site, in the works for more than a decade, would clean up one of the largest abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation. It’s one of more than 500 abandoned mines on the Navajo Nation. But it wouldn’t move the debris far, which is why Navajo residents exposed to the mine waste for more than 40 years oppose the plan. Community members at the April visit urged commissioners to not allow the EPA to move the mine debris to the mill site that has itself been undergoing cleanup for years.

Environment

Take uranium contamination off our land, Navajos urge federal nuclear officials

|

The gale-force winds that swept across New Mexico on Friday, driving fires and evacuations, gave Diné residents in a small western New Mexico community an opportunity to demonstrate first hand the danger they live with every day.Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) members were in the Red Water Pond Road community, about 20 minutes northeast of Gallup, to hear local input on a controversial plan to clean up a nearby abandoned uranium mine. It was the first visit anyone could recall by NRC commissioners to the Navajo Nation, where the agency regulates four uranium mills. Chairman Christopher Hanson called the visit historic, and the significance was visible with Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and other Navajo officials in attendance. As commissioners listened to 20 or so people give testimony over several hours Friday afternoon, high winds battered the plastic sheeting hung on the sides of the Cha’a’oh, or shade house, making it hard for some in the audience of many dozens to hear all that was said. “This is like this everyday,” community member Annie Benally told commissioners, mentioning the dust being whipped around outside by the wind. “They say it’s clean, it’s ok.

Money for abandoned uranium mine cleanup spurs questions about design, jobs

|

This story is part of a collaboration from the Institute for Nonprofit News Rural News Network in partnership with INN members Indian Country Today, Buffalo’s Fire, InvestigateWest, KOSU, New Mexico In Depth, Underscore and Wisconsin Watch, as well as partners Mvskoke Media, Osage News and Rawhide Press. Series logo by Mvskoke Creative. The project was made possible with support from the Walton Family Foundation.

Uranium mines are personal for Dariel Yazzie. Now head of the Navajo Nation’s Superfund program, Yazzie grew up near Monument Valley, Arizona, where the Vanadium Corporation of America started uranium operations in the 1940s. His childhood home sat a stone’s throw from piles of waste from uranium milling, known as tailings.

2022 Special Edition

To create opportunities tomorrow, NM must embrace its strengths today

|

New Mexico’s oil and natural gas industry is growing again, which is welcomed news to lawmakers, communities, and all people across the land of enchantment. Through challenges and changing times over the past two years, our dedication to New Mexico has been unwavering and we’re committed to doing our part to help New Mexico succeed. New Mexico’s oil and gas industry is proud to be the foundation of the state’s economy, providing thousands of jobs across our state and supporting the budget and public schools with billions in revenue. Teachers, students, first responders, and many others depend on our industry for critical resources to support learning, develop the next generation of leaders, and keep our communities healthy and safe. Our state’s role as an energy producer and leader was underscored earlier this year by our ascension to the second-largest oil producer in the United States while remaining the eighth-largest producer of natural gas.

Striving toward net zero, New Mexico grapples with role of hydrogen

|

When Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham announced during the New Mexico Climate Summit in late October she would champion a law to achieve “net zero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, she received accolades from the environmental community.

“Net zero” refers to a movement to reduce and offset through environmentally friendly policies and practices the greenhouse gases that would otherwise reach the earth’s atmosphere. Lujan Grisham’s stated objective builds on an already ambitious goal set in 2019 by the Legislature and her administration to transition New Mexico by 2045 from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy to power its electricity grid.

Getting to net zero by 2050 has become a global rallying cry to halt warming to 1.5° degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, in order to arrest catastrophic impacts of a changing climate. Impacts are increasingly evident now: high-severity drought and wildfires, increasing hurricanes, melting glaciers and rising sea levels.

On paper, the path toward Net Zero sounds simple: drastically curtail current greenhouse gas emitting activities while increasing clean energy and activities that capture greenhouse gases before they enter the atmosphere.

But it’s not simple. Achieving Net Zero encompasses altering all sectors of the economy.And the battle over which path to take toward it can prove vexing.Lujan Grisham has found herself at odds with a who’s who of environmental and community groups over her signature piece of legislation in 2022, a proposed Hydrogen Hub Act, which would provide state incentives like tax credits to support creation of a hydrogen fuel industry.

The governor’s view is that building a hydrogen fuel industry can be a win/win if done right. “For an energy state, it’s more jobs,” she said on a September podcast about hydrogen, and it “gives us a clean energy platform.”

Hydrogen, when burned, doesn’t emit greenhouse gases.

Water

Indigenous feminism flows through the fight for water rights on the Rio Grande

|

Julia Bernal (Sandia, Taos and Yuchi-Creek Nations of Oklahoma) in Sandoval County in the Middle Rio Grande Valley. “It’s like this concept of landback. Once you get the land back, what are you going to do with it after? It’s the same thing. If we get the water back, what are we gonna do with it after?