Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham on Friday struck down the first alcohol tax increase in 30 years meant to address a public health crisis that claims thousands of New Mexican lives a year.Lujan Grisham’s veto came as a surprise to state lawmakers. During weeks of negotiations with the governor’s office and each other during the legislative session, lawmakers had shaped a $1.1 billion tax package only to learn that she had liberally crossed through line after line in the 119-page bill.The decision to eliminate the alcohol tax, in particular, contradicted the rhetoric coming out of the governor’s office this week leading up to the vetoes.

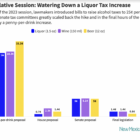

Lujan Grisham sounded the alarm about the potential for the tax package to undermine the state’s long-term financial health. The proposed tax cuts represented future dollars the state would not collect, which some pointed to as a risk given the state’s volatile revenue stream. New Mexico is overly dependent on the boom and bust cycles of the oil and gas industry.However, the nominal increase to the state alcohol excise tax — less than 1 cent on a 12 ounce beer and about one and a half cents per servings of wine and liquor — would have generated roughly $10 million a year.

The tax bill would have directed those dollars as well as about $25 million in money that currently goes to the state’s general fund to a new Alcohol Harms Alleviation fund for treatment.

Unclear is why the governor didn’t eliminate the harm alleviation fund in the tax bill, while keeping the tax increase, given her concerns over shoring up the state’s revenues.

Among those stunned by the governor’s decision Friday was Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, D-Albuquerque, a co-sponsor of the proposal to increase the state alcohol tax.“I would expect an increase in alcohol excise tax would be welcome in light of the harm to the communities and cost to the state due to alcohol,” Sedillo Lopez said Friday afternoon.Maddy Hayden, the governor’s spokeswoman, declined to say why Lujan Grisham had vetoed the alcohol excise tax increase when it would have put dollars into New Mexico’s coffers.She did say, however, “The governor spoke at length to the media (Friday) about the continued need for dedicated resources to address alcohol misuse. As you know, she recommended creating an office at the Department of Health dedicated to alcohol misuse and the budget as signed includes $2 million for that purpose.”Hayden was referring to a Friday afternoon press conference Lujan Grisham held in Santa Fe.In 2021, alcohol killed 2,274 New Mexicans in 2021, at a rate no other state comes close to touching.