State Infrastructure Capital Improvement Plan

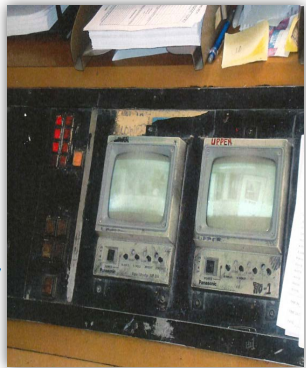

Photo of outdated New Mexico prison security equipment.

Memorials to honor veterans, Bernalillo County public safety officers and gun violence victims.

“Shade structures” at schools and parks.

Improvements for tracks, baseball fields, and basketball and tennis courts and baseball fields.

Those are some of the “infrastructure” projects lawmakers funded by divvying up capital outlay money in 2016.

Meanwhile, a state-owned reintegration center for troubled young people in Eagle Nest requested $673,400 last year for renovations. Photos show sagging floors, torn carpet, broken appliances and other issues.

But the facility run by the Children, Youth and Families Department received only $85,000 for a new security system.

And the Corrections Department requested $21.7 million for general upgrades and $9.6 million for security upgrades at the state’s prisons. They got $7 million.

Those are just a few of the examples of the push and pull in New Mexico’s infrastructure funding system.

And they’re examples some would use when advocating reform of a four-decades old process geared more toward political patronage than the greatest needs.

It’s a system some say should be overhauled, with one of several bills scheduled for consideration by the Senate Rules Committee Friday.

Last year, lawmakers got to allocate $82 million to their own, mostly local, projects. State projects got $84 million, a little more than half of the $166 million infrastructure pie.

“Imagine if they did the same thing for” the budget bill, said Fred Nathan, executive director of Think New Mexico, a nonpartisan think tank pushing for reform. “You’d say that’s absurd, but that’s how they do capital funding.”

This year, state agencies are more likely to get the whole of a considerably smaller, $64 million pie. Falling oil and gas revenues are responsible for the dearth of infrastructure money, as well as other significant shortfalls in the state’s budget.

Some believe the lack of money for local projects this year presents a good opportunity to reform the capital outlay system.

But others are reluctant to give up control of spending that, in flush years, allows lawmakers to spread cash around their districts.

The current system has resulted in about $970 million in unspent money for water projects, public schools, tribal infrastructure and more. Of that, $209 million is for 1,556 projects designated by lawmakers, according to a legislative analysis of Senate Bill 262.

That measure, advocated Think New Mexico, would create an 18-member committee to review and recommend projects for funding. It is on the Senate Rules Committee agenda for Friday.

“It’s still legislators working with other legislators,” Nathan said. “We’re just making it more merit-based.”

SB 262 would allocate at least half of infrastructure money available to state-level projects. It would end the practice of individual lawmakers allocating their own money, with the committee instead making allocations based on recommended criteria.

The proposal suggests the legislative committee “place high value” on projects that:

- Fill critical health and safety needs;

- Create jobs;

- Have additional funding;

- Are fully funded for the entire project or a specific phase;

- Will be maintained and operated by the sponsoring government;

- Is in the infrastructure plan adopted by the state or local government;

New Mexico In Depth re-examined 749 projects that lawmakers included in the 2016 capital outlay bill.

Many of them likely wouldn’t fit the “high value” definition of SB 262.

For instance, originally 512 of the projects weren’t funded at the full amount.

Gov. Susana Martinez vetoed 121 of those projects.

The remaining 391 underfunded projects totaled more than $53 million – more than enough to fund the Eagle Nest youth home renovations and the state prison repairs.

Even critics of the Think New Mexico reform proposal, SB 262, agree underfunded projects are a problem.

“We should be able to make sure that certain projects are going to be fully funded and that the money is going to be spent quickly and that they’re good projects,” said Rep. Matthew McQueen, D-Galisteo. “The process can be made better but I’m not convinced it needs to be thrown out entirely.”

Then there are 204 projects from 2016 that were fully or more than fully funded, at a total cost of $20.5 million. (Martinez vetoed 33 other projects that were fully or more than fully funded.)

Some might question whether the following sampling of remaining projects fulfill critical health and safety needs:

- $345,000 for a memorial honoring Bernalillo County public safety officers.

- $229,000 for a memorial remembering victims of Albuquerque gun violence.

- $320,000 for improvements to open space at a University of New Mexico golf course.

- $110,000 for a veterans cemetery in Taos.

- $100,000 for UNM athletic training room equipment.

- Nearly $700,000 for fully funded shade structures at eight schools and parks, one in Rio Rancho and the rest in Bernalillo County.

- Nearly $555,000 for fully funded track improvements at four Albuquerque schools and one in Santa Fe.

Those are just a sampling of projects that could be questioned under critical health and safety needs criteria.

“We just want to ensure that the dollars are being spent on public infrastructure and things that won’t wear out before the bonds are paid off,” Nathan said. “That means denying if for things that aren’t public infrastructure.”

Such projects highlight the difference between needs in urban and rural areas.

Of all the legislative projects that weren’t vetoed in 2016, 202 totaling nearly $12.5 million went to secondary schools.

Three-fourths of those school projects were based in Bernalillo County, the state’s most populous area. In fact, school projects made up more than half of Bernalillo County’s 2016 capital outlay projects.

Such minor projects likely wouldn’t qualify for the separate capital outlay fund for K-12 schools, which are ranked based on needs and awarded by a committee independent of the Legislature.

Rep. Dennis Roch, R-Logan, is a school superintendent who serves on the legislative oversight committee of the public school capital outlay process. He said his northeastern New Mexico district covers seven counties that have more urgent needs than shade structures or athletic improvements at schools.

“That’s a function of the size of their districts and a lack of true infrastructure needs … like there are in my district,” Roch said.

But the fear of losing infrastructure funding in urban areas was mentioned by Rep. Daymon Ely, D-Corrales, who is instead proposing an interim committee to study the capital outlay process.

“We have capital outlay projects that while necessary do not impact public safety and health,” Ely told one committee that considered House Joint Memorial 4.

That measure initially failed a House vote Tuesday after Republicans argued that such a study could be done by existing interim committees. A second 35-33 vote, in which two Democratic representatives returned to the floor, revived the measure and sent it to the Senate.

The Senate is also considering a resolution, Senate Joint Memorial 24, to create a study committee, and another reform bill, Senate Bill 392. Both are sponsored by Sen. Pete Campos, D-Las Vegas.

Roch is also skeptical of reforming the legislative capital outlay system, although he said the separate public school funding system works well.

“The danger is going from the devil you know to the devil you don’t,” Roch said. “The next system may be worse, it may be more rife with political back scratching.”