Each year, a small group of lawmakers doggedly push for improvements in the state’s disclosure laws related to campaign finance, lobbying, and discretionary infrastructure money available to lawmakers. Here are key initiatives New Mexico In Depth continues to follow.

Steinborn works toward full disclosure of lobbyist spending on lawmakers, bills

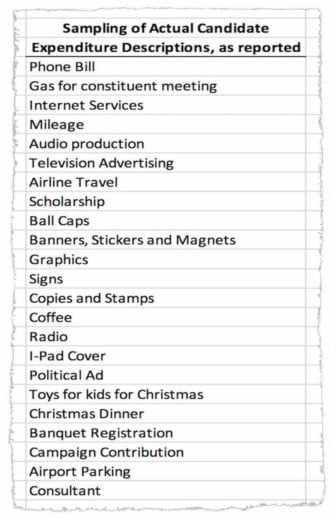

For New Mexico’s volunteer legislators, campaign contributions provide more than just dollars to run an election. The money allows them to crisscross the state to meet constituents or go to legislative meetings. They can pay for telephone costs, stamps, conference travel out of state, and they can be donated to charities the candidate selects. They can help fund other candidates running for office, a way legislators develop potential legislative allies, not to mention power.

For New Mexico’s volunteer legislators, campaign contributions provide more than just dollars to run an election. The money allows them to crisscross the state to meet constituents or go to legislative meetings. They can pay for telephone costs, stamps, conference travel out of state, and they can be donated to charities the candidate selects. They can help fund other candidates running for office, a way legislators develop potential legislative allies, not to mention power.

Since 2013, according to an NMID analysis, lobbyists or their employers have given half or more of campaign funds contributed to 20 percent of all state representatives and senators, and 56 percent of state lawmakers received at least 30 percent (see the data and methodology).

New Mexico is the only state that doesn’t pay its legislators a salary. And lobbyists and their employers don’t mind picking up a lot of the tab they incur in the course of their work.

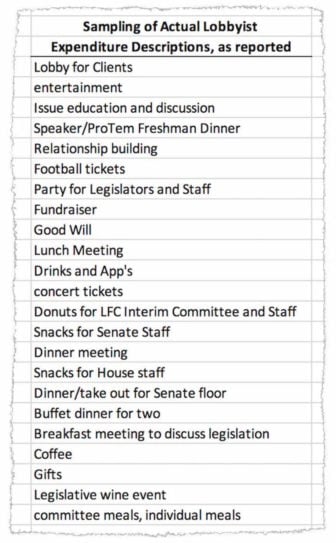

They also don’t limit themselves to contributing cash to influence legislation. Many spend money on advertising, gifts, food and other entertainment to develop relationships with legislators. You’ll find them providing big galas, hamburgers during late night floor sessions, or intimate meals at restaurants.

Campaign contributions are “just a small percentage of the money spent to influence us,” said Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces. “It’s important that citizens of the state know that total number.”

But poor disclosure laws make it impossible to know the full amount of the money spent to influence legislators, or the objectives behind all that money.

Steinborn wants to change that, introducing several bills this legislative session to require public disclosure of the total amount employers spend on lobbying, as well as the specific bills and issues that lobbyists work on during the session.

Polling by Common Cause New Mexico, a good government advocacy organization, shows that 90 percent of New Mexicans think it’s a good idea for lobbyists to disclose the bills or issues they’ve been hired to advocate for.

“Every time we ask if lobbyists have an undue or higher level of influence on elected officials than average citizens do, those (polling) numbers are always incredibly high,” said Heather Ferguson, executive director of CCNM. “The public wants to know which lobbyists are lobbying on which issues and how much money is really being spent.”

The lack of lobbying transparency is one of the “cloak-and-dagger aspects” of the legislative process, said Steinborn. “It’s not always what you see, it’s what you don’t see that’s played the hand of god in killing a bill, or whatever.”

Steinborn has introduced lobbying transparency legislation regularly, first as a state representative and now as a senator. In 2015 as a state representative, he successfully shepherded a bill that required more disclosure from lobbyist employers and mandated that lobbyist reports be publicly available for 10 years rather than two. It’s thanks to that bill that lobbying contributions to elected officials can be accessed by the public going back to 2013. But that same bill saw major revisions before it was passed.

The Senate Rules Committee stripped out language requiring disclosure of what bills or issues lobbyists are working on. And the House Regulatory and Public Affairs Committee removed requirements that lobbyist expenditure reports list each individual lawmaker they spend money on, and it struck a requirement that employers disclose estimates of their full lobbying costs.

The ideas in Steinborn’s bills aren’t novel.

The National Conference of State Legislatures has compiled lobbying regulations of all 50 states, with synopsis of each on its website. A wide swath of states require disclosures of the sort Steinborn is seeking. The NCLS finds that state laws “generally require lobbyists to submit public reports that identify how much money is spent on lobbying, what legislative issues are being lobbied, and for which officials’ benefit the expenditures are made.”

The National Conference of State Legislatures has compiled lobbying regulations of all 50 states, with synopsis of each on its website. A wide swath of states require disclosures of the sort Steinborn is seeking. The NCLS finds that state laws “generally require lobbyists to submit public reports that identify how much money is spent on lobbying, what legislative issues are being lobbied, and for which officials’ benefit the expenditures are made.”

“It takes some courage and fortitude to regulate yourself,” Steinborn said about why some of his proposals meet resistance at the Roundhouse. “It’s not an easy thing to do. It’s very uncomfortable.”

Steinborn is quick to say that the role of lobbyists is important. Everyone deserves an advocate, he said. His bill would simply level the playing field for those who can’t afford to pay their own lobbyist.

“Information and disclosure make citizen participation possible,” Steinborn said. “Without it, frankly, we have a gamed system designed to tilt that pendulum intentionally or through an action to just those who have resources to hire lobbyists and that’s just not fair. And I don’t think that’s healthy for our democracy.”

Wirth hopes for campaign finance reform

Almost a decade-long effort to revise unconstitutional elements of New Mexico’s Campaign Reporting Act will continue in 2019. Sen. Peter Wirth, D-Santa Fe, has slogged away for years to clarify rules for when political activity during elections has to be reported, after a court found back in 2009 that the current law is too broad and therefore unenforceable. Under his bill, independent groups not required to register as political committees but who engage in political activity would have to disclose their political spending along with funders of that spending.

Almost a decade-long effort to revise unconstitutional elements of New Mexico’s Campaign Reporting Act will continue in 2019. Sen. Peter Wirth, D-Santa Fe, has slogged away for years to clarify rules for when political activity during elections has to be reported, after a court found back in 2009 that the current law is too broad and therefore unenforceable. Under his bill, independent groups not required to register as political committees but who engage in political activity would have to disclose their political spending along with funders of that spending.

This go round ought to be easier than earlier years. Once Wirth was elevated to Senate majority leader in 2017, he successfully passed his bill only to see it vetoed by Republican Gov. Susana Martinez, who said it might hinder contributions to non-political charities. Since then, Secretary of State Maggie Toulouse Oliver, a Democrat, has implemented reporting rules for nonprofits that are highly similar to what Wirth has proposed.

During the 2018 election, due to those rules hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on political advertising by nonprofit organizations that aren’t required to register as PACs were publicly reported. Without the Secretary of State reporting rules, none of those expenditures would have been made public.

Now, a group of Republican legislators is suing Toulouse Oliver, saying she overstepped her boundaries in implementing the rules. Regardless of how that court case plays out, Wirth says he’s bringing the bill back because the statute itself needs to be reformed.

Rue won’t drop transparency push for infrastructure money

Back in 2015, as part of a reporting project focused on efforts to reform New Mexico’s infrastructure funding process, New Mexico In Depth decided to look into how individual legislators were divvying up personal pots of public money they are allowed to allocate for building, improving or equipping physical property. A list of each legislator’s funded projects isn’t published online, so we filed a public information request, which was then promptly denied. The Legislature cited state statute to claim they are allowed to withhold the information.

Back in 2015, as part of a reporting project focused on efforts to reform New Mexico’s infrastructure funding process, New Mexico In Depth decided to look into how individual legislators were divvying up personal pots of public money they are allowed to allocate for building, improving or equipping physical property. A list of each legislator’s funded projects isn’t published online, so we filed a public information request, which was then promptly denied. The Legislature cited state statute to claim they are allowed to withhold the information.

Sen. Sander Rue, R-Albuquerque, has introduced bills each year since then to change that secrecy. He’ll do so again in 2019.

Here’s how the process works now:

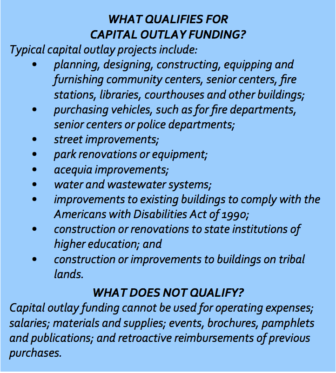

Before the session begins, the Legislative Finance Committee prepares a statewide infrastructure budget, based on guidance from legislative and executive staff, who gather a range of input from state agencies and local governments and districts. That budget goes through the legislative process with subtractions and additions during the session. Once funding is allocated to statewide projects, any remaining funds are divided between the House and the Senate, and each of those chambers then divvy up the money equally among legislators to assign as they see fit. The legislators’ funding decisions are then put together in a collective list that doesn’t show who funded what. And that list is then incorporated into the final budget. The governor will often wield her line-item veto authority to strike out portions of the budget before signing it.

Image from a November 2018 Legislative Council Service Informational Bulletin.

Under the current process, while not necessarily likely, it’s possible that a legislator could claim credit for funding a project without having actually assigned a dime to it. Other sorts of wheeling and dealing could go on that the public has no way of investigating.

Rue’s efforts to bring sunshine to capital outlay allocations haven’t gotten far, yet. Legislators balk, mainly those in rural parts of the state who fear their constituents won’t understand why they didn’t fund a project, even though they may have worked with a group of legislators representing an entire region to prioritize projects with the most pressing need. Legislators fear that publishing their individual allocations will be politicized, with attack ads rolled out against them during election years.

But, Rue says, while he understands those fears and acknowledges there are a lot of differences in the challenges rural versus urban legislators face, how a legislator assigns public money should be made public.

“At the end of the day, it’s taxpayer money,” Rue said. “We should be able to answer their questions and explain what we did.”