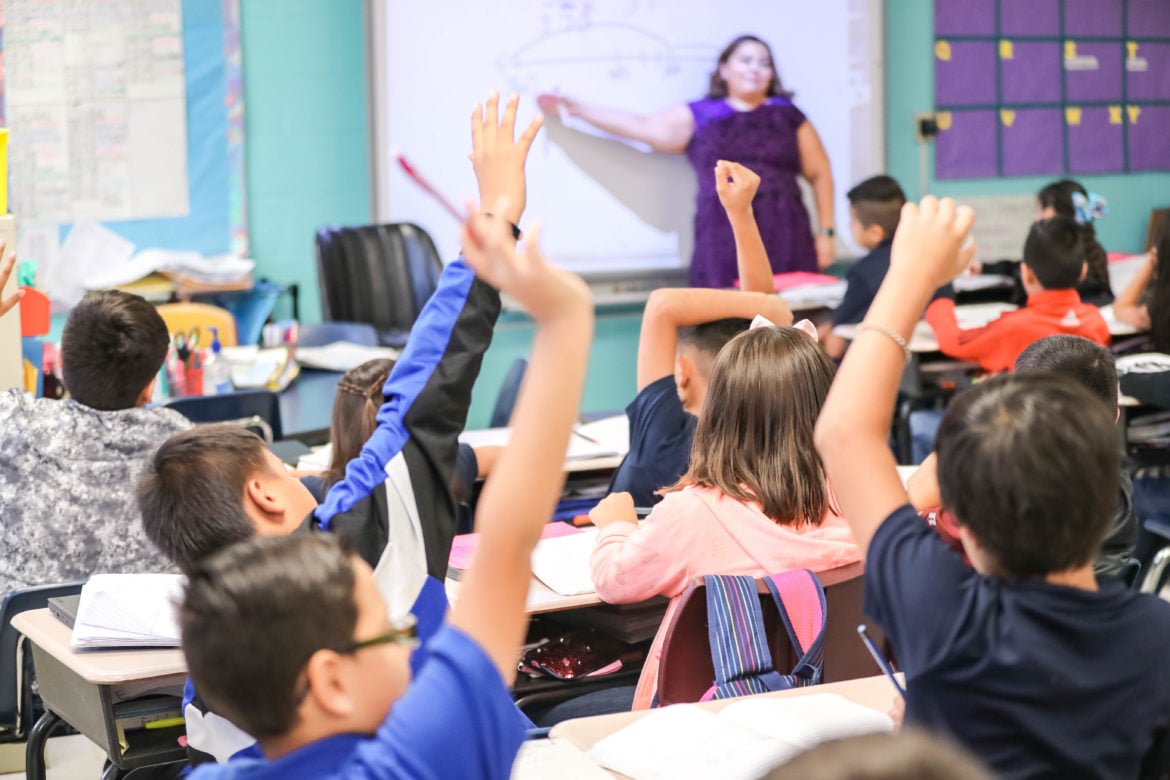

Education

Summit takes stock of education gains, goals for Doña Ana County

|

It’s been five years since the Success Partnership convened its first summit to create goals for “cradle to career” education in Doña Ana County. A lot has changed since then. Ngage New Mexico, an education-focused community organization that created the Success Partnership and organized a follow up summit Monday at New Mexico State University, wanted to put the changes in perspective with a comprehensive look at education data over that period from home visiting and preK to college and workforce training. Since 2015, Las Cruces Public Schools started its first community school to bring social services and after school programs to students and on Saturday the district will inaugurate three more. Graduation rates jumped at two of the county’s school districts, from 75% in 2015 to 86% in 2019 at LCPS, and 67% to 77% at Hatch Valley Schools, while inching up at Gadsden from 81% to 82%.

The all-day gathering was part pep rally to celebrate successes, part tough talk about bumps in the road to better education results and part brainstorming session to chart the course ahead.

Lori Martinez, executive director of Ngage NM, an education nonprofit based in Las Cruces.