Just enough to get people through — not a gallon of bleach, but a 4-ounce mason jar of it, half a dozen diapers, a few cups of beans, a bag of potatoes, some vegetables, a pound of hamburger meat. Almost every day, Albuquerque Mutual Aid volunteers sanitize and pack items, then load them into cars. Wearing masks and gloves, they drop care packages at people’s doors and photograph them to confirm delivery.

The goal: fast, responsive care, particularly for those who might fall through the cracks.

“All the barriers that people run into when they’re trying to access food, that’s what we try to address,” said Selinda Guerrero, with Fight For Our Lives. The organization pulled together with other groups to help people as the COVID-19 pandemic threw some New Mexicans out of work or made venturing out a risk they didn’t want to take.

Roughly 90 volunteers help buy and sort groceries. They take donated food, too, including granola bars and cereal from General Mills that would otherwise be thrown away. Most weeks, the group distributes packages within 24 hours of a request, and has fed up to 1,000 people in a week. Donations have ranged from $3 to people’s entire $1,200 stimulus check.

“We have no requirements — you’re a community member who says you need help, so we’ll help you,” said Guerrero. “When we talk about building the world we want to live in, I absolutely feel like that’s what we’re doing. We’re all going to keep each other safe.”

Food Insecurity In New Mexico

Before COVID-19 hit, New Mexico had one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the nation. That has risen since March with higher unemployment, school closures, and shortages of some food-items. Measuring the increase in food insecurity to date is guesswork, but Feeding America projects one in five New Mexicans, and one in three children, might not know where their next meal comes from. This story is part of a three-story series New Mexico In Depth is publishing that explores various ways New Mexicans have responded to the food insecurity crisis.

Stories in the series:

· Local farms, small gardens see boost in interest, funding to tackle hunger

· Schools revamp meal programs during COVID-19 to curb childhood hunger, with potential to fix long-term problems

· Mutual aid groups rushed to the rescue during COVID-19

Existing social safety nets meant to catch people vulnerable to hunger and homelessness struggled with the enormity of the coronavirus and the changes it wrought. “Mutual aid” groups like the one in Albuquerque sprang up across the state to fast-track food, cleaning supplies, and other basics to New Mexicans facing grim choices as COVID-19 hit this spring. Neighbors helping neighbors.

People lost jobs, the state’s unemployment rate jumping from 4.8% in February to 11.9% in April. Or they were quarantined and couldn’t leave home. Others with compromised immune systems felt they couldn’t risk visiting a store, or didn’t want to bring young children along and had no childcare. Others were unsheltered or lived in hotels. Some had no vehicle to get to a drive-through food bank, or couldn’t sit in hours-long lines due to work or family obligations.

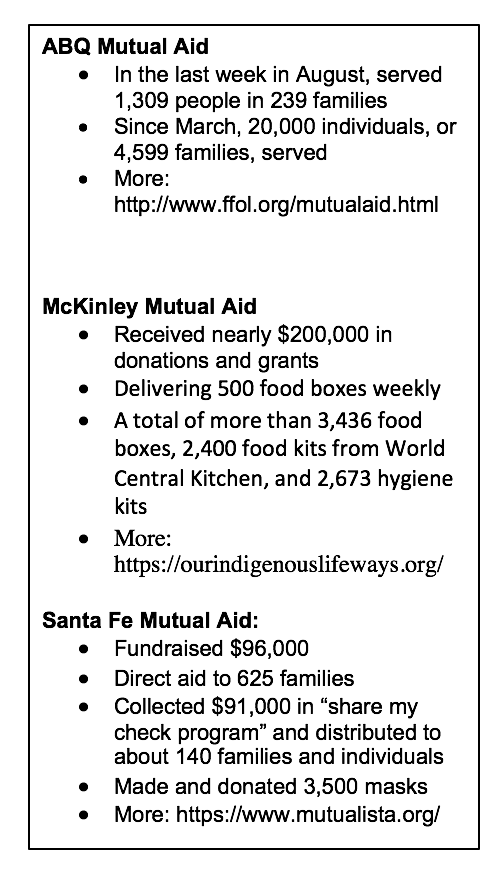

The nimble, volunteer-driven, community-focused groups tout big numbers in who they’ve been able to help.

But food insecurity, a perennial problem in New Mexico, isn’t going away after the pandemic. As mutual aid groups look at how to continue their work beyond this moment, people who have been working toward food security far longer caution that every dollar needs to be spent wisely. Risks include duplicating efforts or skipping potential cost-savings that could better stretch those dollars. Collaborating, instead, could draw on existing efficiencies, both in systems and in cost.

Food packages being prepared by McKinley Mutual Aid. Courtesy: MMA social media.

McKinley Mutual Aid has spent 100 percent of its nearly $200,000 in donations and grants on food, supplies, and gas for delivery drivers, said Krystal Curley, executive director of Indigenous Lifeways. The McKinley County group partnered with other groups in March to launch the mutual aid effort in a county hard hit by the pandemic, where the largest city — Gallup — was locked down in May to get the spread of the virus under control.

They chopped and delivered wood. And they rented a U-haul and drove to grocery stores as far away as Farmington in neighboring San Juan County, in search of hard-to-find supplies.

“We didn’t know what we were getting ourselves into,” Curley said. “We just saw a need and so went for it.”

They soon established regular food supply chains with wholesale food suppliers Ben E. Keith and Pueblo Fruits, as well as local indigenous farmers, and provided 40-pound food boxes to 250 families per week, enough to feed a family for five days. The World Central Kitchen added another 250 packages with produce and dry goods.

McKinley County and Gallup lie amid a patchwork of tribal, private, federal, and state lands. With weekend curfews on the Navajo Nation, and not many organizations venturing out to offer help, the increase in need was real.

“We helped fill in those gaps when others couldn’t,” Curley said. “We weren’t trying to duplicate services, just trying to get to places where it’s really hard — Pueblo Pintado, Torreón, even Ramah.”

Often, food boxes go to senior centers or elderly residents in smaller communities outside Gallup.

“Some of the elders, before they bring a food box into the home, they bless the food box with cornmeal,” Curley said, “I thought we were just giving food to somebody, but when I heard that story, it’s like, wow, it’s more than that.”

Members of McKinley Mutual Aid deliver packages to Pueblo Pintado Chapter. Courtesy MMA.

In Santa Fe, groups banded together to deliver groceries and medication to people who can’t leave their homes, or to raise relief funds, said Mary Ann Maestas, with Earth Care.

Santa Fe Mutual Aid Network delivered $91,000 from Santa Feans who donated their economic stimulus checks to mixed-status or undocumented individuals and families, $500 to $1,000 at a time. They’ve also raised another $96,000 for 625 families, most of them in Santa Fe County, to help with groceries or utility bills.

The Santa Fe group began with word of mouth and then distributed flyers around the city in both Spanish and English. When phone calls come in, Maestas said, they work to connect people with existing resources, like the local food bank and housing assistance. They’re coaching volunteers, too, to consider what they have to give, even if it’s just sharing produce from their backyard garden.

“It’s been a lot of trying to address these needs right away as they come up,” Maestas said. “Families really are hurting, especially mixed-status families, or undocumented families in Santa Fe, because they have been intentionally left out of federal aid resources.”

A Santa Fe Mutual Aid mask making station. Courtesy of SFMA.

There’s no question that minimizing the number of times people have to leave their homes to go to the grocery store helps reduce the virus’s spread, said Jill Dixon, development director with The Food Depot, northern New Mexico’s food bank. To that end, The Food Depot offered drive-through pick-ups of 25-pound bags of food.

Need has increased, she said: Before Covid-19, they saw about 1,200 people each week. One Thursday at the end of April they recorded helping 3,772 people. That number dropped as unemployment and food benefits expanded, but is expected to rise this fall. In the long run, making every philanthropic dollar count will matter because experts predict the pandemic will linger while donations may drop off, leaving a population in need.

Going forward, she hopes organizations and government officials looking to help will consider what The Food Depot and other food banks do before repeating their efforts. Then, if there’s a neighborhood or a community missing a food pantry, or someone is available to do home deliveries, she said, that’s a partnership to be built. To that end, The Food Depot is collaborating more with the City of Santa Fe and Santa Fe County CONNECT, which helps people find needed services.

Collaborating can help everyone do more. It leads to lower prices for commodities through purchasing in bulk, and increases the chances that gaps in service are addressed, too.

“When we’re bringing in food, we’re bringing in by the semi-truck load, and as an example, pinto beans cost us $.20 a pound instead of $1,” Dixon said. “Our partners get that price.”

Organizers for all three mutual aid groups say they hope to continue beyond the Covid-19 crisis. Each faces its own challenges, though they largely center on whether the backbone of these efforts — volunteer time and community donations — will continue.

“What we’ve built through the pandemic, the daily distribution of resources, I don’t know how we’ll continue, but it’s clear something is needed,” Guerrero said. The Albuquerque group had cut back to five days a week of food delivery, but with increasing requests for help in August, added a sixth.

As people return to work, volunteer capacity is changing. Santa Fe Mutual Aid is moving toward “phase two,” ending delivery of prepared meals to health care workers and looking at adding a tutoring program or neighborhood pods where families with kids going to school online trade responsibilities.

Maestas hopes people will continue to look out for their neighbors in the winter and fall. “Stopping something just because there’s a vaccine or something like that, that’s not really how we approach community change and solidarity,” she said.

What food box delivery would look like on rural, unpaved roads in McKinley County through winter driving conditions, Curley hesitated to consider. She hopes that even if their current deliveries don’t last, the pandemic has drawn attention to gaps in the healthcare system and the social safety nets.

“We would still like to educate our community and our leaders and our decision-makers on what we experienced and really push them to make those changes,” Curley said.

There’s a need for housing and access to clean water, mobile food pantries and food distribution sites, she said, or a grocery store, in smaller, more remote communities.

“Our food insecurity has always been there, it just saddens me that it took a pandemic to highlight all these issues,” she said. “We just have to take that opportunity to really tell our stories, to tell people, this is what we were dealing with. McKinley, the Navajo Nation, we were not prepared for this disaster at all.”