A toddler in his father’s lap struggled to keep his arm still while Amber Awelagte took his blood pressure.

“Stay still or it will get tighter,” she told the boy. Her calm demeanor seemed to soothe the boy as she finished up then sent him to get tested for COVID-19.

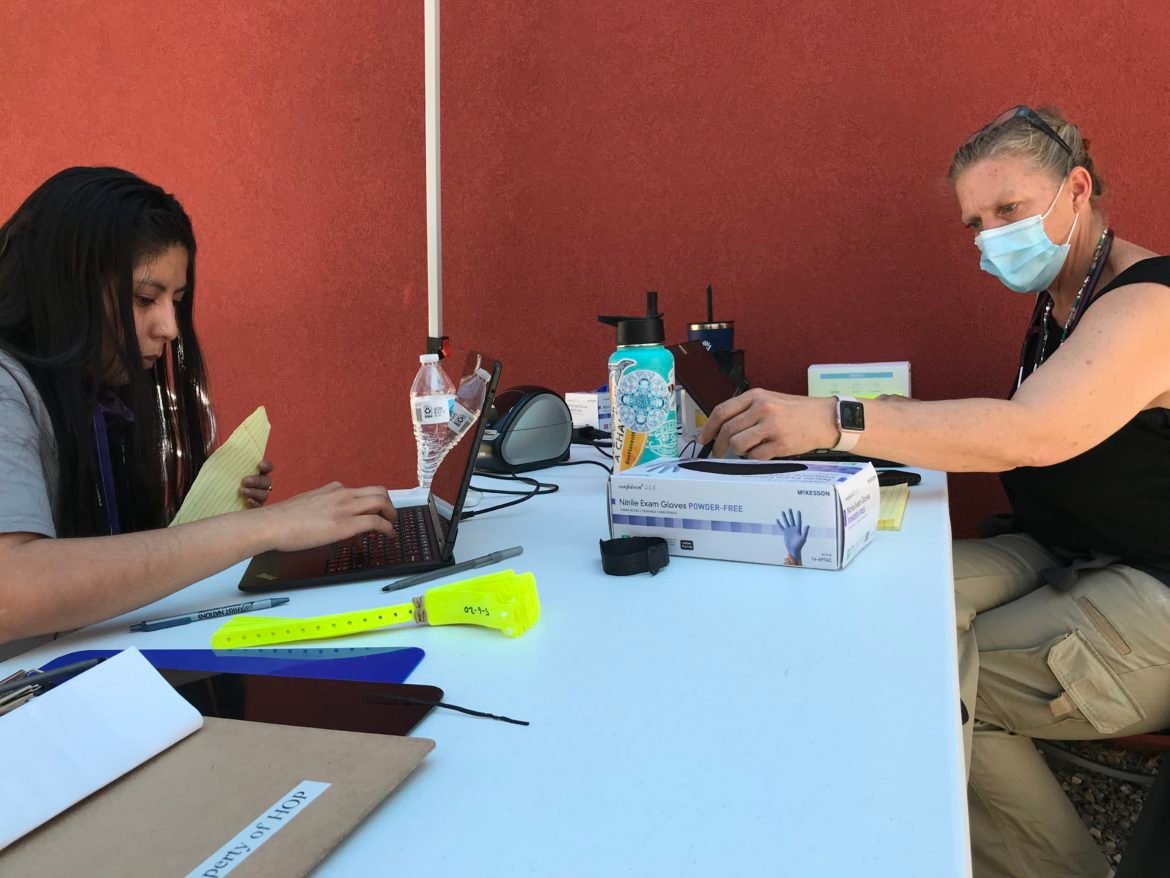

In many ways it was a typical day for Awelagte, the lead medical assistant for the Homeless Outreach Program (HOP) at First Nations Community HealthSource, a health center with several clinics in Albuquerque serving the city’s large Native American population. Awelagte provides health services targeting urban Indigenous people in Albuquerque experiencing homelessness.

But unlike most days, on Wednesday First Nations offered testing to their unsheltered clients for the new coronavirus, even if they had no symptoms.

“It is kind of scary to think about it, I don’t want none of my patients getting sick and it’s sad. What is going on in the other Native communities is really bad,” she said. “I just want to try and help and slow it down over here.”

It’s no secret that New Mexico’s tribes are severely impacted by COVID-19.

Statewide, Native Americans account for 56% of those who’ve tested positive for the virus, while making up just 11% of the state population. Reported data from the Navajo Nation, as well as Zuni, Zia, San Felipe, and Kewa Pueblos, provides some data about which tribal communities are grappling with virus outbreaks. But those reports only represent about 28% of the known cases in the state.

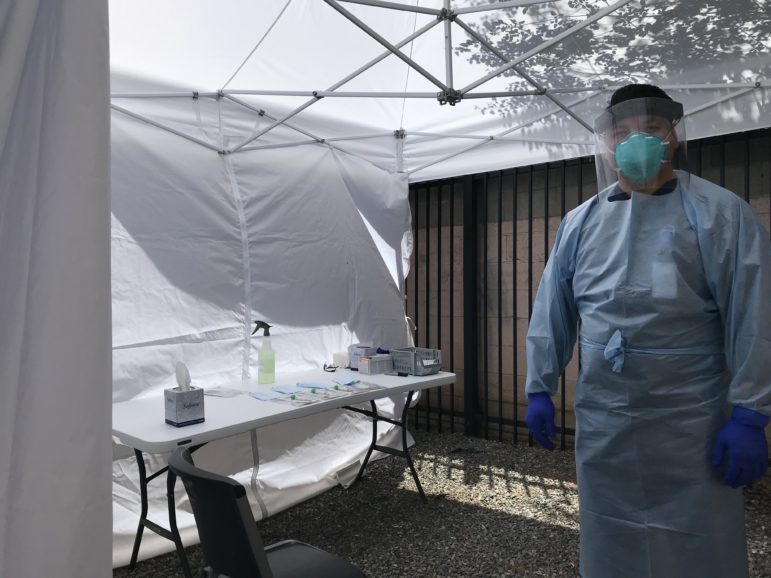

Charles Maes administered COVID-19 tests to 40 people at First Nations Community HealthSource. Shaun Griswold/New Mexico In Depth

Unclear is whether a significant outbreak has swept through the Native community in Albuquerque. The regional Albuquerque Indian Health Service told New Mexico In Depth that 42 of 331 positive cases identified by its facilities are in Albuquerque, which is home to about 22,500 Indigenous people. But the state is not releasing county or city level data about the race or ethnicity of those who’ve tested positive, so it’s unclear how many Native Americans are represented in the 1,012 positive cases in Bernalillo County.

With help from the New Mexico Department of Health, First Nations tested 40 of its high-risk, homeless patients on Wednesday at its clinic in the heart of Albuquerque’s International District.

“We really wanted to provide the testing that needs to be done for this population, that they don’t have access to,” First Nations CEO Linda Son-Stone said, and “hopefully save lives.”

“We have not yet seen any community spread in the unsheltered population in Albuquerque,” said Rachel Murphy, a nurse practitioner and lead for the center’s homeless outreach program.

But it’s just “a matter of time,” Murphy said, because Indigenous and homeless cultures are communal, with a lot of sharing.

“It’s a mindset not only with the Indigenous culture but also with the homeless population,” she said. “‘We take care of each other out here, this my street family, I’m not going to let someone go hungry. If I’m eating a burrito I’m going to give them a bite.’ Because of that infectious diseases can spread more quickly.”

Wednesday’s testing event aimed to detect if there is community spread in the unsheltered community, she said, and if so, if there are identifiable hot spots that can then be controlled. “If we have zero positives in the southeast quadrant” of the city, she said, “we’ll feel pretty confident that at this point it hasn’t penetrated into this area, and we may consider testing in a different part of town.”

In addition to the tests administered on Wednesday, First Nations arranged for homeless clients to be given surgical masks, and put up in a hotel while they await their results. Putting them up in a hotel, Murphy said, will prevent spread if any of her clients test positive.

Murphy’s clients include people from every New Mexico tribal community. She said she’s on a first-name basis with most, even knowing their nicknames. While she knows where most of her clients usually stay at night, providing them a hotel room ensures First Nations can readily contact them and provide adequate follow-up health care if they need it.

At the hotel, Murphy said, the toddler and the other three members of his family would receive three meals a day and, if anyone tests positive, proper treatment and isolation to prevent spread of the virus.

First Nations will expand its testing to all Indigenous people in Albuquerque, on Saturday, with 400 COVID-19 tests available on a first come, first serve basis at no cost, at its facility located at 625 Truman St. NW. The drive-thru site opens at 9 a.m., and people do not need to schedule an appointment or show any symptoms to receive a test.

“Given the significant impact on Native American communities, especially on the reservations that were hard hit by COVID-19, we need to make sure we can test family members that are in Albuquerque,” said Son-Stone. A key concern, said Son-Stone, is people who might be traveling to and from their reservation communities, transmitting the virus from one place to the other.

For Awelagte she’ll continue to follow up with the people tested and continue to work with people that would be at her clinic for daily services. This work is personal. A member of the Zuni Pueblo, she has several family members that tested positive for COVID-19.

“I feel really sad about it, I know several people in Zuni that I’m related to that have it. It’s real heartbreaking to me,” Awelagte said. “I feel positive that I’m giving a helping hand.”