As the crow flies, the Pojoaque Primary Care Center is about 20 miles from New Mexico’s 400-plus-year-old capital, Santa Fe, with its art galleries, well-known opera and tourist destinations. But it’s 45 minutes by car from Dr. Mario Pacheco’s home on Santa Fe’s south side.

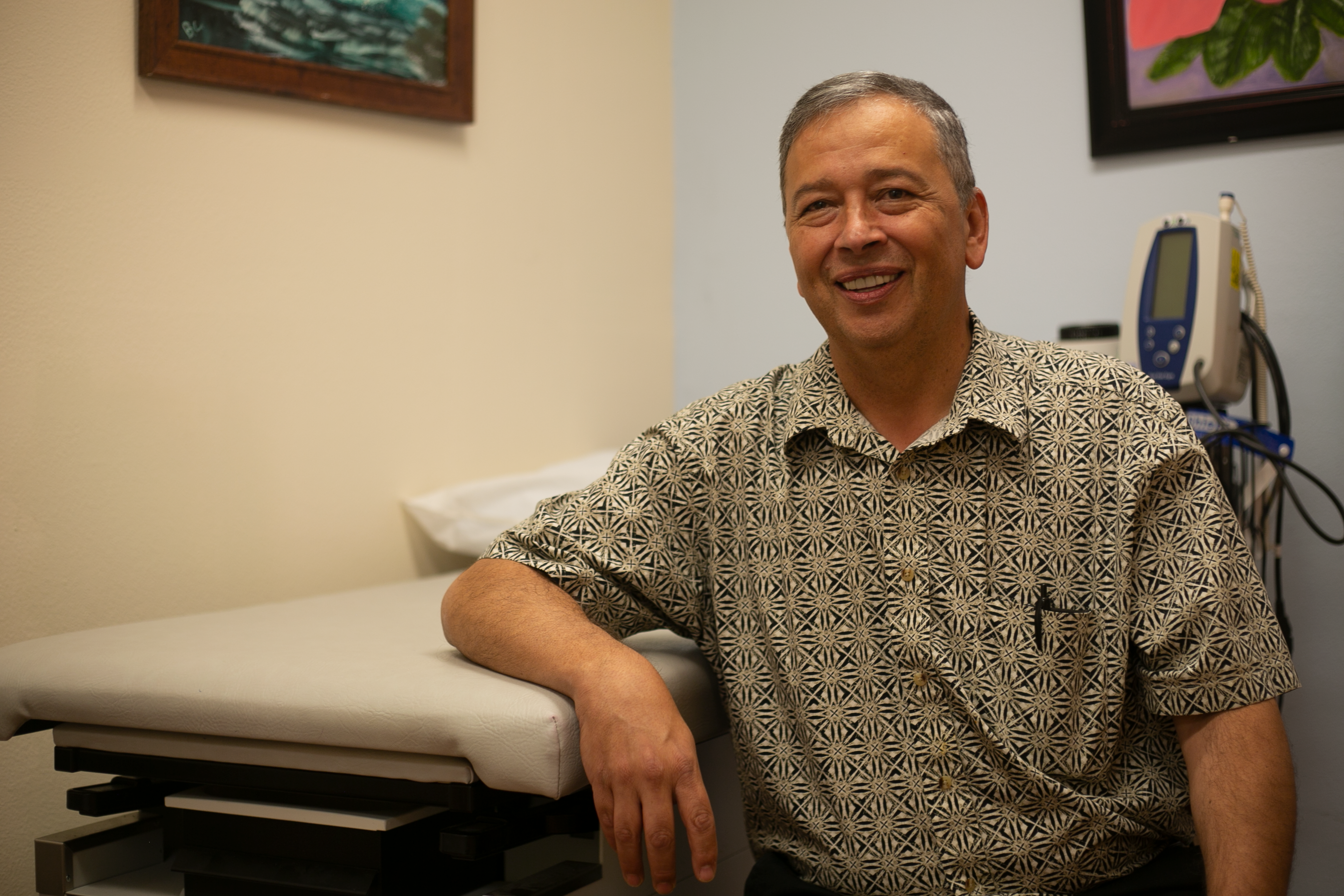

With roots in a small northern New Mexico town himself, Pacheco makes the drive from Santa Fe to serve a rural clientele that largely comes from northern Hispanic communities in the greater Pojoaque Valley. “I’m serving patients that I could really see as being my uncle or my aunt or my dad or my mom,” he said. “These are people who can relate to me and I can relate to them.”

New Mexico has a severe shortage of healthcare workers like Pacheco, particularly in the state’s rural and frontier areas, where a third of the state’s 2.1 million people live. Lawmakers and the governor invested millions to close the gap earlier this year, but advocates say it’s not enough.

“We don’t have enough doctors anywhere in New Mexico, but especially in rural New Mexico,” Pacheco said.

Dr. Mario Pacheco practices family medicine at the Pojoaque Primary Care clinic and spends about 20 percent of his time directing the University of New Mexico’s Health Extension Regional Offices, through the Office for Community Health. New Mexico has a shortage of physicians across the board, he said, especially in rural communities. Image Credit: Marjorie Childress/New Mexico In Depth

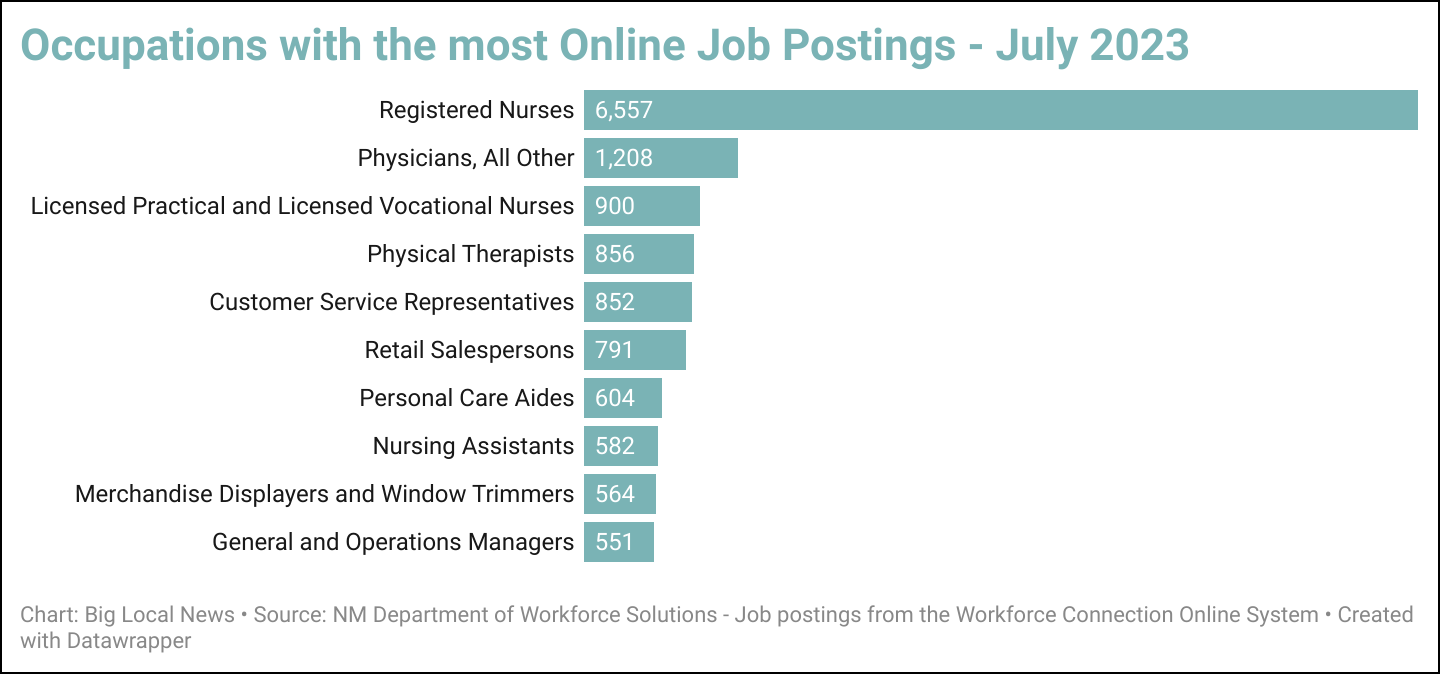

The challenge is large: in July the state was short 1,000 physicians and almost 7,000 nurses, according to published job announcements around the state.

And the need is only expected to grow as baby boomers retire and strain the already-overburdened system, without a guarantee that a new generation will replace retiring medical professionals. Every state is confronting too few medical professionals. That means New Mexico competes nationally, even internationally, for a too small pool of nurses, doctors, and other health workers.

As it now stands, not everyone believes New Mexico is well positioned for the high-stakes competition.

Policymakers in Santa Fe, the state’s capital, approved a budget this year that would put more money in physicians’ pockets and reduce their costs. They even set up a fund that would provide $80 million over three years to help expand or start rural healthcare businesses.

But those steps have come against a backdrop of historic state surpluses, and weren’t large enough to close significant deficits that make other states more attractive.

It didn’t help that Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, a Democrat, struck a provision meant to help retain healthcare workers in rural areas in omnibus tax legislation that she gutted with line-item vetoes. (Last month, fellow Democrat, Rep. Miguel Garcia of Albuquerque and the sponsor of the rural health care tax credit, challenged the governor’s vetoes in state court.)

“We’ve got to do everything we can,” said Linda Siegle, a registered lobbyist for the nursing association who has worked on healthcare issues for the better part of 40 years.

Annie Jung, executive director of the New Mexico Medical Society, the professional association for physicians, agreed there is no silver-bullet solution. “We need the shotgun approach.”

The fifth largest state by land mass, about a third of New Mexicans – 800,000 – reside in far flung rural and frontier towns and counties that, if contiguous, would be slightly larger than the state of Colorado just to the north. In about a quarter of New Mexico’s rural counties, along the eastern and western edges, white people predominate. But as a whole, Hispanics and Native Americans compose the majority of New Mexico’s rural population, just as they do statewide. New Mexico’s population is nearly two-thirds non-white.

Compared to their urban counterparts, rural New Mexicans earn less, per capita, and fewer have earned high school diplomas. The lack of doctors, nurses and other health care workers in the sparsely populated reaches of rural New Mexico exacerbates persistent health inequities.

A 2019 assessment by New Mexico’s rural health planning working group is sobering. The state’s rural communities have lower life expectancy, experiencing higher rates of disability, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic liver disease.

Many rural New Mexicans drive long distances to go to a hospital or a primary care clinic or to access basic medical services: lab work, x-rays, pharmacies.

“It’s a huge barrier,” Pacheco said of the transportation challenges rural residents face. “Usually, if you’re 15 minutes late, your appointment gets canceled. So what if there’s a car accident? What if your car breaks down, if something comes up that you have no control over? And so we have to change that system…I have people traveling in two and a half hours, I’ll never cancel those appointments.”

In an emergency, lack of transportation can be deadly. “You can call an ambulance and wait for them to come and get you,” said Jung. “You can get in your truck and drive into town. Both of those are difficult and both of them will delay care.”

And forget hailing a ride. “You don’t just call an Uber,” said Matthew Probst, a physician’s assistant working at the school-based health center at West Las Vegas High. In addition to clinical work, Probst, who like Pacheco is Hispanic, with roots in both the northern village of Tierra Amarilla and in Nambe Pueblo, serves as the Director of Community Rural Engagement for the University of New Mexico’s Health Sciences Center. He champions the creation of a “hub and spokes” transportation system to help people travel to urban centers where they can access clinics, labs, and hospitals.

Matthew Probst stands at the door of an exam room at West Las Vegas high school in northern New Mexico where he works as a physician assistant. Recently named director of Rural Community Engagement for the University of New Mexico Office for Community Health, Probst advocates for the state to grow its own healthcare workforce, starting with education and mentorship of students in middle school, or even younger. Image Credit: Marjorie Childress/New Mexico In Depth

Rural New Mexicans have struggled with inequities for generations.

“With hardship comes resiliency…there’s no loss, there’s only lessons and every time you take that hit, you learn from it,” Propst said.

Both Probst and Pacheco advocate for “growing our own” health care workforce — recruiting people more likely to live in rural New Mexico.

Probst founded Semillas de Salud, a program at a clinic based in Las Vegas, New Mexico that educates and mentors young people to think of health care jobs as within their reach. Particularly important is that they see people from their own communities doing health care work. “The mentors are people like me,” he said, “so they look at me and say, well, I can do it…he talks like me, he looks like me, he’s got that big accent that he doesn’t cover up.”

“Recruiting our healthcare workforce from rural New Mexico would go a long way towards the likelihood of people practicing in those areas,” said Pacheco, who spends a portion of his time every week as director of UNM’s Health Extension Regional Offices. “…there’s a number of approaches and there’s a lot of good programs, but there’s just not enough of them and there’s not enough support for it.”

Siegle, the nursing advocate, told lawmakers at a July interim committee hearing that the only solution is for the state to recruit and mentor its own people to become nurses. “Every country in the world has a nursing shortage, and we have been trying to steal nurses from other countries,” she said. “That is not going to solve our nursing shortage.”

Thousands of jobs for nurses, physicians, and other health professionals are posted around the state each month.

New Mexico’s rural health care tax credit is one way state leaders try to retain practitioners in rural areas. Currently, certain types of medical professionals qualify if they practice a specified number of hours in a rural or underserved area.

“Everything’s more expensive in the country, right?” said Probst, who has received the tax credit each year. “Whether that’s gas, it takes more miles to get to places, etc. So it’s a way to kind of even the playing field in terms of distribution in New Mexico, of where healthcare workers are.”

The tax credit makes a huge difference, Pacheco said.“I get to count my transportation time, the time that I’m seeing patients, and I think the tax credit is another example of something we can do to try to retain people, even if they’re not living in rural New Mexico.”

Expanding eligibility for the tax credit to a wider set of professions is a longstanding recommendation of the New Mexico Health Care Workforce Committee. This year, lawmakers embraced that suggestion, including an expansion into an omnibus tax bill that included a range of tax measures. Had the governor not vetoed the expanded tax credit, which she did along with a plethora of other tax measures in the bill, a new set of health care workers could claim the credit next year – pharmacists, behavioral health and physical therapists, registered nurses, and social workers.

“These five professions are kind of essential workers,” said Garcia, the measure’s sponsor who is suing the governor in court.. “…right now we have rural communities that don’t have one social worker, this workforce is essential to maintaining good health outcomes for our people.” Garcia said rural areas struggle to access the services of the other professionals he included in the expansion, as well, and he made a special point of how important nurses were during the COVID-19 pandemic. “R.N.s were at the frontline, in the trenches, having to deal with the COVID after-effects,” he said.

Garcia declined to comment on his lawsuit until the outcome, but in a press release his attorney, former State Sen. Jacob Candelaria, said the governor didn’t have the authority to line-item veto a tax bill.

Earlier this year, the governor publicly and through a spokesperson to New Mexico In Depth, said she made the vetoes out of concern that, taken together, the money that would not be collected due to the measures — credits, deductions and other breaks are so-called tax expenditures — could imperil the state’s long-term fiscal health.

Whose job is it?

One tax measure Lujan Grisham didn’t stand in the way of was the elimination of New Mexico’s version of a sales tax on deductibles and copayments paid by people with private insurance. In some counties, the tax reaches 8%, and by law it can’t be added by medical providers to a patient’s bill. It was a “fantastic” step that advocates had been trying to get for 16 years, Jung said.

But while acknowledging lawmakers’ progress this year, the medical society executive director said much more needs to be done.

Lawmakers allocated $80 million over three years to help companies in rural areas who serve Medicare and Medicaid recipients expand services or open their doors — down from an initial request for $200 million in a year with an unprecedented budget surplus.

They increased the amount of money the state will reimburse medical professionals for providing Medicaid funded services.

Medicaid, the national health insurance program for low-income people, is “the cornerstone” of most medical practices, Jung said. Half of New Mexico’s population is enrolled.

But the new Medicaid reimbursement rates are still lower than in surrounding states like Arizona, Jung said, which makes it harder to convince physicians to practice in New Mexico. “It’s a huge bump, and will help the current providers, but our 100% is only 70% of Arizona,” she said. “…the reimbursement rate in the state has got to be increased.”

Lawmakers also increased the state loan-repayment program for physicians who practice in underserved areas. Now, physicians may receive $75,000 over three years to help pay their student loans, up from $50,000 over two years, and the program was expanded to cover all doctors.

But lawmakers appropriated just half of the amount the governor requested. According to legislative analysts, there were 649 eligible applicants last year, but only 44 new awards were made because of the available budget.

When testifying before legislative committees, Siegle poses a rhetorical question to spur thinking about the different responsibilities of government and schools of nursing: Whose responsibility is it to solve the healthcare workforce shortage?

Data Siegle presented to the Legislative Health and Human Services Committee in July shows many more people apply to nursing school than are admitted, or who actually graduate.

Some changes to help more New Mexicans become nurses could be made by schools themselves – like dropping some of their prerequisites that aren’t applicable to nursing, like algebra – but ultimately, schools will only expand slots in their programs if they have the funding, she said.

Lawmakers have made significant investments in nursing education since 2020, specifically $10 million a year to higher education to grow schools of nursing, but it’s not enough, Siegle said. “We have to grow our own and that’s going to require the state of New Mexico to not just one time but continually provide funds to the schools of nursing so that they can expand the number of nursing slots that we have.”

This reporting is part of a collaboration with the Institute for Nonprofit News‘ Rural News Network, and the Energy News Network, Flatwater Free Press, Mississippi Free Press, New Mexico In Depth, Religion News Service and Sierra Nevada Ally. Support from the Walton Family Foundation made the project possible.