A bill meant to modernize New Mexico’s marriage laws would increase the money people pay to the state’s county clerks for a marriage license. Meanwhile, the bill’s sponsor, Democratic State Sen. Daniel Ivey-Soto, is paid by numerous county clerks on a contract basis for technical, legal and training services.

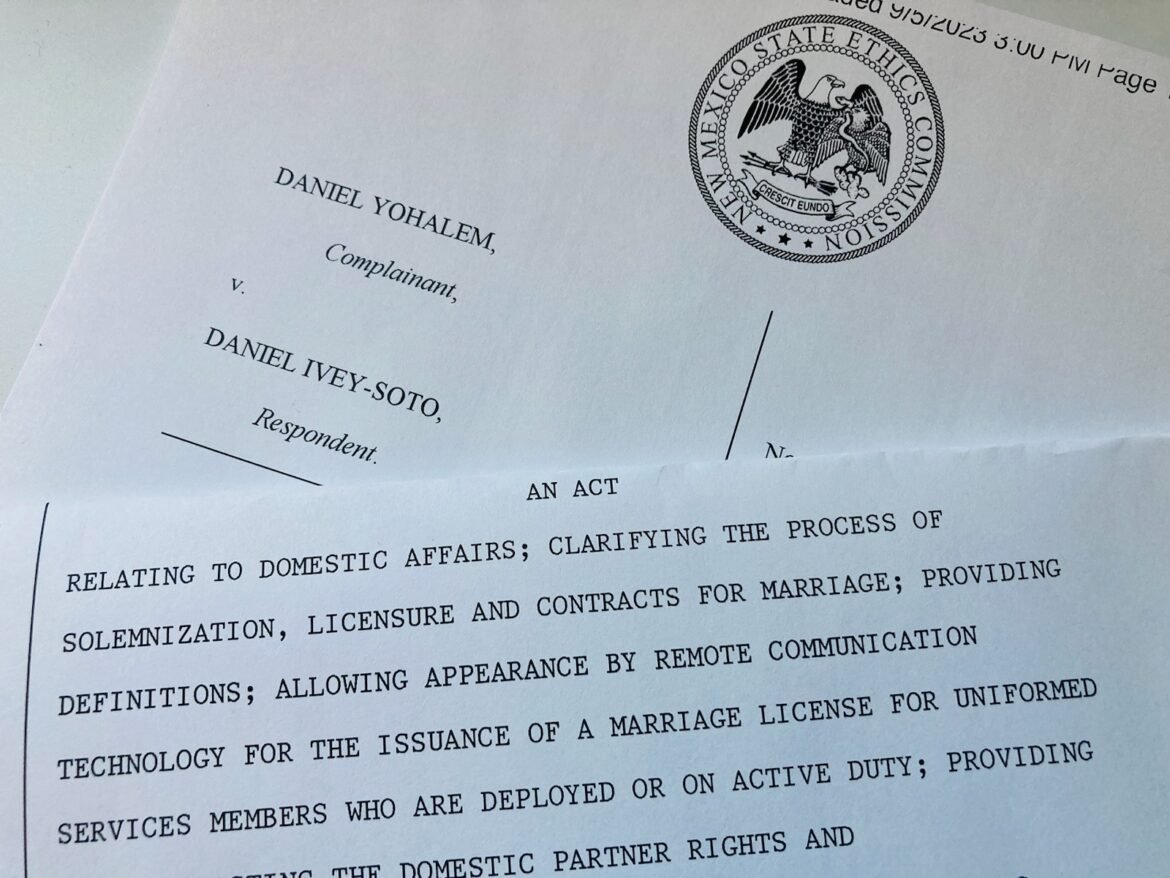

As the State Ethics Commission investigates complaints made last year that accuse Ivey-Soto, in part, of using his position as a lawmaker to curry favor with his clients, lawmakers are considering Ivey-Soto’s House Bill 242.

The legislation’s aim, according to Ivey-Soto and his co-sponsor, Rep. Doreen Gallegos, a Doña Ana County Democrat, is to dust Victorian era moral codes off New Mexico’s books. For instance, it would prohibit marriage of 16 and 17 year olds, which are allowed with parental consent, to people more than four years older than they are. The bill also allows anyone over the age of 21 selected by the couple to officiate at a wedding. And deployed military members could receive a marriage certificate via webcast. The bill also creates a new domestic partnership law and makes other changes to marriage and divorce laws.

Yet for all the bill’s public benefits — making marriage easier for many in a state with one of the lowest marriage rates in the nation — the legislation also contains a goodie which Ivey-Soto said the state’s 33 county clerks have been craving for years: Higher fees.

Under the bill, marriage certificate fees would increase to $40 from $25. In addition, the bill would increase the cost for marriage licenses between people who don’t have an address within the state even more, to $80. Certificates for domestic partnerships, a new form of state legal recognition under the legislation for couples, would cost $40, too. And deployed military members who get married via webcast would have to pay an additional $40 fee to process a necessary declaration of military service.

The bill earned praise from Republicans and Democrats, for the most part, as it sailed through two House committees where marriage jokes were more common than partisan bickering.

But the ethics complaints against Ivey-Soto filed last summer by Santa Fe attorney Daniel Yohalem raise a question about whether there’s a line between where law making ends and money making begins.

Ivey-Soto acknowledges he derives part of his yearly income from local fees collected by county clerks. This bill would increase fees collected by those same elected officials.

Over the years he has maintained, as he did in his company’s 2013 annual report, that as a state lawmaker, he has no conflict of interest because his payments come from local taxes and fees paid to local governments, rather than from state appropriations.

In an interview Monday, Ivey-Soto said whether the marriage license fees are increased or not would have no bearing on whether county clerks hire him in the future. “There is not a single county for which that is the case,” he insisted. “Not a single county.”

In the last state in the union to not pay lawmakers a salary, such questions about whether a lawmaker is privately benefiting off otherwise sound public policy may always exist.

New Mexico’s 112 state lawmakers do receive a stipend — it’s $191 a day during the 30-day session that ends Thursday —and are reimbursed for travel, around 67 cents per mile. Most lawmakers have day jobs, and current discussions about paying lawmakers in the future don’t usually envision barring lawmakers from having outside jobs if they are eventually paid a semblance of a salary.

But how much freedom do lawmakers have to help clients — or constituents for that matter — with whom they have a financial relationship, especially when that legislation leads to more money for those clients?

An interim legislative ethics committee composed of members of the state House and Senate in 2019 offered guidance. Ivey-Soto, an expert in elections law and parliamentary procedure, in an interview said he relies on that opinion to guide his legislative conduct.

“The right of members to represent their constituencies is of such major importance,” the legislative guidance reads, “that members should be barred from voting on matters of direct personal interest only in clear cases and when the matter is particularly personal.”

“We are expected to bring our professional expertise to the legislature,” Ivey-Soto said, citing a different section of the opinion. “Given the expertise that I have, I would be remiss if I did not bring that to bear for the benefit of the people of New Mexico.”

But the ethics committee also wrote that the “polestar for managing potential conflicts of interest is disclosure.”

Current law does not require Ivey-Soto to disclose to his fellow lawmakers or the public that county clerks are his clients or how much of his income every year comes from work he does for them.

Damon Ely, a former Democratic state lawmaker who was deeply involved in helping to pass the law setting up the state ethics commission, as was Ivey-Soto, said conflicts of interest are always going to exist in a volunteer legislature.

But Ely said he thought lawmakers who make income from local governments should disclose those clients, because it’s important for the public to know if state lawmakers are earning money from local governments while they appropriate state money to them.

“The question is: Are people going to get open about it?” Ely said.

Lobbyist allegation

On February 2, during an executive session of an otherwise public meeting, New Mexico’s state ethics commission approved Executive Director Jeremy Farris’ request to extend for another 90 days an investigation into whether allegations against Ivey-Soto merit a public hearing, New Mexico In Depth has learned.

The law requires the executive director to make such requests every 90 days, according to a commission spokesperson. Yohalem’s complaint alleges Ivey-Soto violated three ethics and transparency laws – the Governmental Conduct Act, the Financial Disclosure Act and the Lobbyist Regulation Act.

Farris in a Sept. 10 letter detailed which of the allegations fall within the commission’s jurisdiction, and referred those to his general counsel for investigation. (Farris jettisoned several claims because they occurred before the commission was formed in 2019.) Citing confidentiality rules, the ethics commission would not comment on its investigation stemming from the complaint.

The complaint, which was publicly disclosed by other media outlets last year, in part alleges that the northeast Albuquerque Democrat — even as a sitting state senator — should register as a lobbyist on behalf of the clerks.

Deputy Secretary of State Sharon Pino wrote in an Oct. 10 letter that the office was “unable to find compliance violations” of the lobbyist regulation act and referred the case back to the commission. The Secretary of State’s office, under an agreement with the ethics commission, investigates allegations of breaches of the lobbying statute.

Pino wrote that the finding is based on a review of the complaint as well as evidence submitted by Ivey-Soto, whose lawyers said he has “not been employed nor compensated as a lobbyist for the New Mexico County Clerks Affiliate at any time since the time he took office as a New Mexico state senator in 2013.”

Ivey-Soto’s attorneys argued in a letter to the Secretary of State that under the state’s lobbyist regulation act, a legislator can never be considered a lobbyist because the act excludes lawmakers from that category. Ivey-Soto sought a dismissal of the complaint.

But Yohalem, in a motion arguing against the dismissal, claimed that a close reading of the lobbyist regulation act does not provide a wholesale exemption to lawmakers from registering as lobbyists.

It is not known if the state ethics commission is looking at whether Ivey-Soto should register as a lobbyist, and such a decision won’t be made public by the agency unless the commission finds probable cause that Ivey Soto violated the statute.

Working for the Clerks

At the core of Yohalem’s allegation is a perceived conflict of interest between work that Ivey-Soto does for county clerks and his work as a lawmaker. The lawmaker has a long history working for the New Mexico county clerks association or as a contractor for individual county clerks.

After resigning as the state’s Elections Director under Secretary of State Mary Herrera in March 2008 Ivey-Soto became the executive director of the county clerk’s affiliate of the New Mexico Association of Counties. Ivey-Soto in an interview said that the position’s duties included government relations, so he registered as a lobbyist for the affiliate.

He also carved out a niche business providing professional services to county clerks through NM Clerks LLC, which he formed in 2008, according to the Secretary of State’s records.

In 2019, Ivey-Soto incorporated Vandelay Solutions as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and in 2021 began listing that nonprofit as his employer, describing his work as “technical assistance & training for local government officials & key stakeholders.” In its first three years, the nonprofit would earn $407,500 in revenue, according to tax filings.

Through his law firm, InAccord, Ivey-Soto has represented counties before the New Mexico Supreme Court.

Clerks themselves have questioned whether Ivey-Soto wears too many hats. Lea County Clerk Keith Manes in an interview verified an email contained in Yohalem’s complaint in which he raised such concerns to another clerk.

“When I came into office in 2017, I paid him in April because I thought we were supposed to,” Manes said of a contract the county had with Ivey-Soto’s company. “And then I got to look at that and I thought, ‘I’m not contracting to pay somebody to run my office. You know, I should be running it.’ Because everybody just calls Daniel and says, ‘What should I do?’ And he would tell them. And I didn’t think that was right.”

“Daniel knows a lot about elections, but I don’t need to call him every day with questions from my office,” Manes, a Republican, added. “I can look up statutes.”

Marriage proposal

Over the past decade, Ivey-Soto has carried numerous bills directly having to do with the work of county clerks, including how elections are run.

The marriage reform bill this year is an example.

Republicans and Democrats have praised the marriage bill for allowing military members to appear through webcast to receive a marriage license and for added restrictions regarding the marriage of minors.

The proposal, if passed, would also increase the amount of money counties collect from people getting married. Legislative analysts estimate that roughly 6,500 couples get hitched each year in New Mexico.

“There are aspects of this that the county clerks have been pushing for a long time, particularly with regard to the fees,” Ivey-Soto told members of the House Judiciary Committee during a Feb. 7 hearing.

” … [T] he [marriage license] fees have not been raised since before I was born,” Katherine Clark, Santa Fe County Clerk, said in testimony supporting the bill at the House Governmental, Election and Indian Affairs Committee’s Jan. 29 meeting. The fee increases would provide “a little bit of money to go into the clerk’s fund for archiving and other functions in the clerk’s office,” she said.

But a share of the new revenue would not go into a state-administered grant-funding program that helps abused and neglected children, the Children’s Trust Fund.

Under current law $15 of every $25 marriage license goes into the fund. HB 242 would hike the marriage license fee 60% without a commensurate (or any) increase in fee revenue to the Children’s Trust Fund

“Nobody’s asked for it,” Ivey-Soto said when asked Monday why the fund did not receive a 60% increase in payments. “We’ve made some inquiries as to whether or not the fund needed additional revenue … we didn’t get a response back.”

Gallegos, Ivey-Soto’s co-sponsor in the House, said in an interview that she agreed to introduce the proposal upon requests from the Clerk’s Affiliate and then Ivey-Soto.

Ivey-Soto “has a contract I think with the clerks somehow, and I don’t know what it is,” Gallegos said, unprompted.

“It’s kind of his day job; he does some of their work — or he has in the past,” she added. “And so it was a bill that he had been working on.”

So far, the bill has sailed through two House committees without a dissenting vote. On Tuesday afternoon, it was on the House floor calendar but had not been taken up for a vote.

Disclosure: Santa Fe attorney Daniel Yohalem represented the Santa Fe Reporter in its 2013 lawsuit against former governor Susana Martinez. The author of this story was a party to that case. (New Mexico First Judicial District Case No. D-101-CV-2013-02328).