This is an example of New Mexico In Depth’s mid-week newsletter, that our readers received via email on Wednesday, Feb. 7. We think it’s crucial to stay in touch and tell you what’s on our minds every week. Our newsletters aim to do just that. We’d like to hear what’s on your mind, as well. Or, got tips? What do we need to know? Contact us: [email protected]

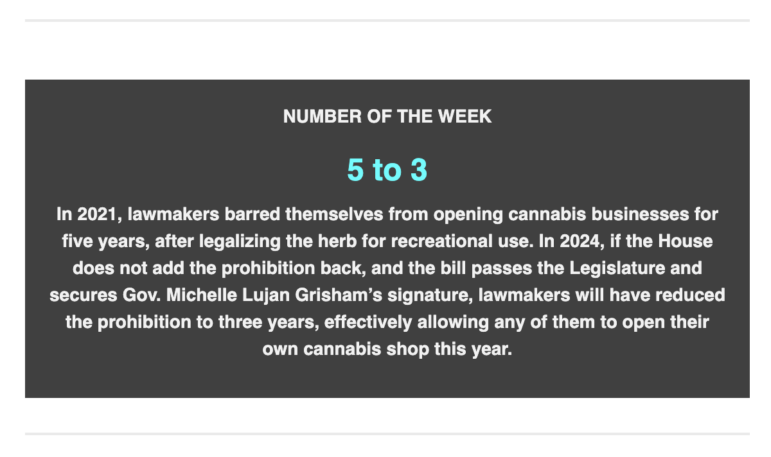

When lawmakers in 2021 legalized recreational cannabis they also created rules for how a new cannabis industry would function. One of the rules they came up with was temporary – any sitting lawmaker on the date the law went into effect would have to wait five years before opening their own cannabis business. This week, two years earlier than that five-year mark, senators got rid of that rule by amending a bill making changes to the cannabis statute.

I rewatched the floor debate back in 2021 to jog my memory about why the prohibition was placed on lawmakers in the first place. I wrote about it here.

The debate three years ago made clear the rationale – lawmakers wanted to prevent conflicts of interest, or at least the appearance of them, when voting for a bill creating a new industry. As one lawmaker put it, none of them should be “first in line” for getting a cannabis license.

This year, the amendment to remove the prohibition quietly moved along after showing up in a substitute bill presented in the Senate Judiciary committee. It wasn’t until it reached the senate floor Monday that there was any substantive discussion, after Sen. Harold Pope, an Albuquerque Democrat, offered an amendment to keep the prohibition until the original 2026 date. Debate ensued.

The most striking? Two Republican senators, Mark Moores of Albuquerque and Cliff Pirtle of Roswell, both of whom have announced they won’t run for re-election, were the prohibition’s biggest advocates in 2021, but its biggest detractors in 2024.

The two vigorously supported Sen. Stuart Ingle, their Republican colleague, three years ago when he asked for the prohibition, and took most of their Republican caucus with them in voting for the amendment.

This year, the two vigorously opposed the prohibition, and took most of their Republican caucus with them.

Moores in 2021 invoked disgraced Democratic Sen. Phil Griego who served time in prison for pushing the sale of a government building he later earned a hefty broker’s fee from, and asked sponsors of legalization to state whether they had any financial interest in creating a new cannabis industry. This year, he said “…we should not penalize legislators from having the economic opportunity that this body decided was a legal product.”

Back in 2021, Pirtle said the prohibition was “prudent” and “fair”. “I think it really gets to the heart of some of the concerns of many of the people in the state that somehow the reason for pushing this legislation is that legislators are going to use this as a way to generate revenue,” he said.

This year, Pirtle wanted its removal. “We all work in different areas, whether it’s lawyers, teachers, farmers, and I think it’s a very slippery slope,” he said, while pointing out that the prohibition barred lawmakers from opening a company, but they could still provide legal or other services in the cannabis industry, as some attorneys in the Senate may have done.

Their arguments this year articulated the challenges of a citizen legislature in which most lawmakers must work other jobs to support themselves. These arguments were the principal reason many voted against the prohibition in 2021. The volunteer nature of the Legislature is often lauded, but it also brings challenges. It helps if one is retired or has an independent source of income to serve in the Legislature. But for many, serving in the state house is out of reach – those with lower-incomes, who are young and establishing their careers, or who juggle parenthood and a day job, and can hardly afford to add the significant demands on a lawmaker’s time.

Moores disclosed he was a sponsor of the amendment this year that gets rid of the prohibition, and also said he had no plans to open a cannabis business when his legislative service ends, after this year’s session.

Moores and Pirtle weren’t the only senators who changed their stance this year. Pope himself voted no to adding the prohibition in 2021. Among the Democrats, numerous flipped their votes one way or the other, and the Republicans as a caucus, flipped almost en masse.

The two were just the most striking because they so publicly advocated for the prohibition in 2021, and this year so publicly sought to get rid of it.

In the best case, it’s an illustration of how thinking changes over time, especially if you’re a lawmaker actively engaged in the evolution of public policy through the years.

As to public perception – which is so central to the trust that people have in their government – it doesn’t help that the two are both retiring after this session, a move that will give them a lot more time for other priorities, like making money.

I’m the first to acknowledge that I don’t personally experience the challenges that come with serving in the New Mexico Legislature, subject to partisan attacks and constant public scrutiny, and having to juggle a day job to boot.

We talked a little about this last week during one of our weekly online chats about the session, and I noted then the amount of unpaid work that goes into being a lawmaker. It’s clear to anyone who watches the New Mexico Legislature year in and year out.

There are benefits, certainly, that obviously make the role desirable. If you’re an extrovert, you get a lot of people’s energy. If you are passionate about public policy, you get a direct hand in creating it. At the end of the day, you have power.

But in recent years we’ve also seen several people – younger women of color, specifically – give up service in the Roundhouse because they needed to focus their attention on making a living, raising children, or simply their mental health.

The volunteer nature of the work makes it a challenge to have a diverse state house – particularly in the upper echelon of leadership, those who are able to stay in the body for the long haul. By diversity, I mean what you might expect – people of different races, genders, and incomes who bring their lived experiences to bear on public policy.

The debate over whether lawmakers who ushered in legal cannabis can open a cannabis business after three years rather than five must be considered in this light. The discussion on the senate floor this year was a prime opportunity to consider how perceived conflicts of interest harm public trust. But much of the focus – in 2021 and today – was instead on being fair to lawmakers who must work day jobs.

In recent years, there’s been a growing conversation among lawmakers about whether or not it’s time they earn a salary. That’s a consideration that’s ripe for bringing into these sorts of debates, directly, rather than hinted at in laments about the need to make a living.

Bill would amend current law to allow lawmakers into cannabis biz early