Tucked away on the northern New Mexico portion of the 27,000-square-mile Navajo Nation is a green oasis in an otherwise arid, often overgrazed landscape. The region, which received only 3.8 inches of rain in 2020, is home to one of the largest tracts of contiguous farmland in the continental United States.

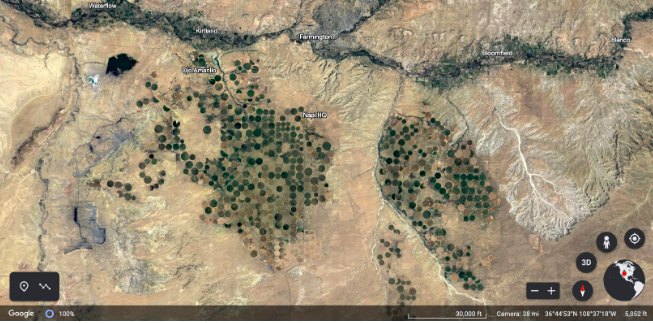

Water from Navajo Lake flows through 70 miles of canals before heading down an additional 340 miles of lateral irrigation ditches to a sea of roughly 700 central pivot-irrigated circles. There, the Navajo Agricultural Products Industry, known as NAPI, grows blue cornmeal, whole sumac berries, and juniper trees, among other culturally relevant foods under the Navajo Pride label.

This story was originally published by Civil Eats

Alfalfa and corn are the top cash crops, however. Total sales have made NAPI profitable enough to contribute over $1 million to the Navajo Nation in 2020. “The rangeland is depleted,” says Delane Atcitty, the executive director of Indian Nations Conservation Alliance and a NAPI board member. “That’s why the alfalfa [for cattle feed] is selling.”Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

But NAPI would make a lot more money if it sold all the alfalfa off the reservation. Instead, it balances tribal food security with economic development. Locals can buy Navajo Pride products at an outpost near NAPI headquarters and at outlets such as Walmart off the reservation, but the Navajo Nation’s 13 grocery stores typically don’t carry the products.

The farm, located near Farmington, New Mexico, a small town with a 19.9 percent poverty rate, spans almost 72,000 irrigated acres. However, it should have 110,630 irrigated acres.

A Google Earth view of NAPI’s center-pivot irrigation. One inch in this photo is equal to about five miles.

The U.S. government has yet to uphold its end of a deal struck over 60 years ago, in which the Navajo Nation traded some of its water rights to divert San Juan River water, a major tributary to the Colorado River, to the growing urban areas along the Rio Grande in exchange for irrigation infrastructure for NAPI. Sixty years later, and as water resources dwindle, the remaining 40,000 acres of irrigation originally promised to the farm remain undeveloped.

Tribal communities typically have the most senior water rights in a region—at least on paper—yet they often lack the resources to build infrastructure to utilize the water. As a result, not only have Southwestern tribes’ ability to farm been compromised, but approximately 30 percent of the Navajo Nation has no access to clean, reliable drinking water. Currently, about 25 percent of Native communities receive some form of federal food assistance, but tribes would prefer to expand the markets for Native American farmers.

As water grows scarce in the West, two different branches of government are sending mixed signals on tribal water. One the one hand, the Biden administration recently announced that $13 billion from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law would be invested directly into tribal communities, including $2.5 billion to implement the Indian Water Rights Settlement Completion Fund, which will help deliver long-promised water resources to tribes. And there is more focus than ever before on tribal water settlements, 34 of which had been enacted by the Department of Interior (DOI) by 2021.

On the other hand, later this month, the Supreme Court will hear a high-profile case in which the federal government has decided to push back on its responsibility to provide tribes with an adequate water supply. In 2003, the Navajo Nation sued the DOI and the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona arguing that the 1868 treaty established the Navajo Nation reservation as a permanent homeland and pledged support for agricultural settlement, and therefore required the federal government to provide water.

Last year, the Ninth Circuit Court upheld the fact that the Navajo reservation’s purpose expressly included farming. Most of the 16,000 farms in the Navajo Nation are family-owned, and there is no other commercial farm the size of NAPI. While the Supreme Court case, which will be heard on March 20, was not brought on behalf of NAPI, any decision the top court makes could impact the massive operation. For example, water rights settlements on the Colorado River and Little Colorado River could decrease overall water available for NAPI to utilize.

The implications of the case are striking, says Dylan Hedden-Nicely, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, head of the Native American Law program at the University of Idaho, because the Navajo Nation “wants to use this [river] water for agricultural and production and economic development while also freeing up groundwater for domestic use.”

Center-pivot irrigation waters some of NAPI’s crops. (Photo courtesy of NAPI)

All of this is taking place despite that fact that the critical need to provide water on arid reservations was made clear all the way back in 1865, during the first congressional appropriation debate for irrigation of what was then called the Colorado River Indian Reservation.

“Irrigating canals are essential to the prosperity of these Indians. Without water, there can be no production, no life; and all they ask of you is to give them a few agricultural implements to enable them to dig an irrigating canal by which their lands may be watered and their fields irrigated, so that they may enjoy the means of existence,” a delegate from the territory of Arizona said at the time.

Of course, just because the government understands the need doesn’t mean its leaders have felt responsible to meet it, say Native water right experts. “We have arrived at this existential threat because, after 200 years, there’s still no structural place for tribes to engage in the water policy conversation at a level that acknowledges their sovereignty and their self-determination,” says Daryl Vigil, co-director of Water & Tribes in the Colorado River Basin and water administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation, of the state of the Colorado River negotiations amid the Supreme Court case.

And without adequate water, tribal communities in the region have often been unable to develop their water resources to achieve food sovereignty. And, if NAPI—a profitable, efficient agricultural operation run by members of the largest tribe in the U.S.—is still owed water infrastructure according to a 60-year-old treaty, what confidence should the other 29 Colorado River Basin tribes have that their water needs will be met?

An undeveloped plot of land in the Navajo Nation prior to irrigation being introduced. (Photo courtesy of NAPI)

Broken Promises

Congress approved the creation of Navajo Indian Irrigation project (NIIP), which made irrigating NAPI possible, in 1962 and completed San Juan-Chama project in 1973. But there has been minimal federal funding to develop irrigation infrastructure on the remaining tracts of NAPI land since 2011, according to Lionel Haskie, director of operations for the farm.

Unfortunately, NAPI’s story isn’t unique. “There are a lot of outstanding claims from [Native American] nations to water,” says Laura Bray, a research scientist at the University of Oklahoma. If anything, she adds, NAPI’s plight “is exemplary of the failure of the U.S. government to provide adequate water, something very basic for sustaining society.”

Vigil agrees. “In the Upper Colorado River basin, 40 percent of the tribal water rights have been unused because of their inability to participate in conservation programs and inability to develop water rights usually because of a lack of infrastructure funding,” he says.

At the same time, tribes are doing their part to conserve water. In 2022, NAPI used only 60 percent of its diversion rights, according to the farm’s CEO, Dave Zeller. “NAPI does not bank any unused water. The unused water is released from Navajo Dam by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, where water managers can then decide whether it flows down into Lake Powell,” he said via email. “That’s water rights going down the river,” adds Atcitty. He says the capacity to develop water infrastructure is the key to tribes’ ability to take responsibility for their own food systems.

“I don’t think the federal government wants NAPI to fail because that would reflect poorly on them, but there doesn’t seem to be much incentive on their end to build the project out with the water [the farm] is not using yet [but] is entitled to,” says Zeller.

And NAPI is operational for only eight months of the calendar year. “The canal system would need to be winterized annually if it was to operate 12 months a year,” adds Zeller.

Tribes Are at the Center of Water Negotiations in the West

Tribes are positioned to play a significant role in the larger effort to balance water demand and supply in the region. Currently, 22 of the 30 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin have recognized rights to use 3.2 million acre feet of Colorado River system water annually—approximately 22–26 percent of the basin’s average annual water supply, according to the Water & Tribes Initiative, a group of tribal members, water experts, and nonprofit organizations working to enhance collaborative decision-making in the basin.

And the amount of water under tribal control is only likely to grow as the remaining 12 tribes settle unresolved water rights claims.

“These unfulfilled promises, like to NAPI, prevent tribal sovereigns from being able to create their first-time economies for themselves.”

Daryl Vigil, co-director of Water & Tribes in the Colorado River Basin and water administrator for the Jicarilla Apache Nation

Long-term in the region, “there’s only two sources of new water rights in the Colorado River basin—agricultural water and Indian water,” says Daniel McCool, a political scientist who studies Native American water rights at University of Utah. “That’s where the action will be in the next few years.” Just last week, the Klamath tribes, senior water users on the river, called for more water, which could prove devastating for farmers in the Rogue River Valley and Medford irrigation districts.

The Supreme Court case promises to clarify the degree to which the federal government has an obligation to provide water to the tribal reservations it created. “Tribes are the weakest actor in water rights and allocation—part of that is historical, [as they were] purposely excluded from the Colorado River Compact (completed in 1922),” says Andrew Curley, a Diné member who studies water governance and Indigenous geography at the University of Arizona.

Vigil adds that while tribes may have senior water rights, they often have no way to leverage those rights into usable water. “We just want the same opportunities [to develop water infrastructure] that was afforded to other stakeholders,” he says. The federal government wanted to assimilate tribes by turning them into farmers and ranchers. “These unfulfilled promises, like to NAPI, prevent tribal sovereigns from being able to create their first-time economies for themselves,” says Vigil. “And if you can’t create self-sustaining economies, it’s really hard to start thinking about how you feed yourselves.”

“No water was ever allocated in the Colorado River basin willingly by Western politicians. They were forced to do it by the courts,” says McCool. For most of the 20th century, Western states and the federal government ignored Native American water rights when developing water projects, he adds. In fact, he says, “the first time the Anglo water holders along the Colorado River said, ‘Let’s bring the Native Americans to table,’ is when they had to engineer cutbacks.”

In most cases, Native water rights date back to the establishment of reservations and supersede state water law. One case in 1908—Winters vs. United States—determined that tribal rights to water are based on future need rather than past use and are not forfeited if tribes don’t exercise their claims.

“The Winters doctrine” is the tool still used by the one branch of government that has been most supportive of tribal water rights—the courts. “The Winters [precedent] has been a pretty big hammer for the last 100 years,” says McCool, “but we may see the big hammer disappear altogether with this conservative [Supreme] Court.”

Cattle graze on NAPI land, with irrigation equipment in the background. (Photo courtesy of NAPI)

Paper Water vs. Wet Water

Jason Robison, a professor of law at the University of Wyoming, shares McCool’s concerns about how the current Supreme Court could reshape the federal government’s trustee obligations toward tribal water rights.

The water in the Colorado River is already overprescribed, as climate change has reduced precipitation in the region over the last decade. “This basin’s hydrology has changed, but water use has not changed commensurately and the basin’s reservoirs are heading toward bankruptcy,” says Robison.

In a bid to save water over the last few years, for example, largely non-Indigenous farmers along the Middle Rio Grande received payment to voluntarily fallow their land and not use water. But tribes don’t enjoy payment for the water rights they don’t use. “There’s undeveloped [Native American] water rights that are considered system water,” says Crystal Tulley-Cordova, the principal hydrologist in the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources.

To decrease demand on Colorado River water this year, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is aiming to pay farmers in California and Arizona to fallow their land as well. “Yet many Navajo families live in poverty while the water they have rights to gets used by others,” says Heather Tanana, a Diné member and law professor at the University of Utah. “Everybody, historically, was taking [tribal] water without any consideration of the impact to tribes, or what would happen when tribes did develop.”

For tribal communities, it’s a difficult moment to push for more water given the ongoing shortages. “Everyone is being pushed to conserve,” says Tulley-Cordova. “Tribes aren’t at the same level as everyone else; our big push is to secure our water rights, so we have a more secure and sustainable water future.” By that she means what are often called “wet water rights”—actual access to water, not the rights that exist on paper.

As a result, tribal communities spend an inordinate amount of time and money protecting the water they do have. “[Tribes] were promised this water, and now have to spend millions to protect it,” says Hedden-Nicely, who is a co-author of this amicus brief in support of the Navajo Nation. “And we have a solid chunk of our membership that are living in absolute poverty.”

“If the federal government is not going to fulfill their obligation as per law, then it should buy NAPI out [of its water rights].”

Navajo Indian Irrigation project CEO Dave Zeller.

As the Supreme Court wades into water relations, any decision promises to have far-reaching consequences. And the current court hasn’t shied away from upending precedent. “The worst-case scenario is that our whole system of water management in the West is disrupted,” says Tanana. On the other hand, “if the case recognizes an enforceable federal trust responsibility, then we’ll likely see more paper rights turning into wet rights,” says Tanana.

The stakes couldn’t be higher for tribes throughout the West. “Water negotiations right now are essentially fighting over what’s left,” says Curley. And crises have typically forced tribes to take less than they deserve. “That’s how colonialism has played out for tribes—’Take a bad deal now or lose even more later,’” he adds.

Regardless of the Supreme Court decision, it’s unclear whether NAPI will be able to irrigate the remaining 38,000 acres. Although the farm has received over $9 million in appropriations through the Water Infrastructure Improvement for the Nation Act since 2019, it has struggled to secure the estimated $242 million from the government for deferred maintenance costs on its existing irrigation infrastructure.

Zeller says NAPI needs an answer from the government either way so it can take steps to keep the farm profitable. “As expenditures on fuel, labor, and fertilizers continue to rise, NAPI’s revenues have grown stagnant because we can’t grow the farm out anymore,” he says. “If the federal government is not going to fulfill their obligation as per law, then it should buy NAPI out [of its water rights].”

Still, UW’s Robison is optimistic the enormous farm will ultimately prevail for two reasons. “Of the 30 basin tribes, the Diné have developed impressive capacity for water management,” he says. And, he adds, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act have set aside considerable water development funding for basin tribes.

“The most important thing is that tribes have the sovereign capacity to make their own decisions about water,” says Hedden-Nicely. “Ultimately, food security is going to be an integral part of that, but it could be to grow food for their own membership or to develop their economies.”

Atcitty agrees. “To us, true tribal sovereignty revolves around agriculture and means being able to feed your own people,” he says.