The Santa Fe New Mexican chronicled how efforts to increase taxes on alcohol over the past 30 years have hit a brick wall at the Roundhouse. Lawmakers budged in 2023, raising the tax per drink by a penny — far short of a 25 cent proposal. Illustration by Marjorie Childress.

Ever seen someone make a quarter disappear?

You did if you watched this year’s legislative session, where advocates seeking to stem the state’s tide of alcohol-related deaths proposed a 25¢-per-drink tax — and lawmakers shrank it down to hardly a penny.

Instead of funding $175 million in alcohol treatment and prevention, the final legislation will raise $10 million.

Alcohol killed 2,274 New Mexicans in 2021, at a rate no other state comes close to touching. Last fall, influential lawmakers signaled they might finally address the crisis with the systematic strategy experts say it demands, including one of the best-studied approaches: raising alcohol taxes to make it more expensive to drink excessively.

How could lawmakers look at so vast a problem and do so little?

As is typical at the Roundhouse, supporters and proponents clashed in public hearings. But the outcome hinged on a fatal arithmetic error made by the bill’s most devoted sponsors, and an eleventh hour vote by a handful of lawmakers who over the past decade had taken thousands of dollars from alcohol businesses.

Low odds, high hopes

No one had any illusions that raising alcohol taxes would be easy. In the 30 years since lawmakers last upped the state’s rates, repeated attempts to raise them ended in failure. In 2003, Democratic Gov. Bill Richardson flirted with raising alcohol taxes, but spurned by the Legislature, he never tried again. In 2010, Rep. Brian Egolf, who would later become Speaker of the House, lost his own effort after battling with alcohol interests. The most recent proposed tax increase, in 2017, didn’t pass its first committee, with liquor lobbyists flatly telling lawmakers they wouldn’t negotiate.

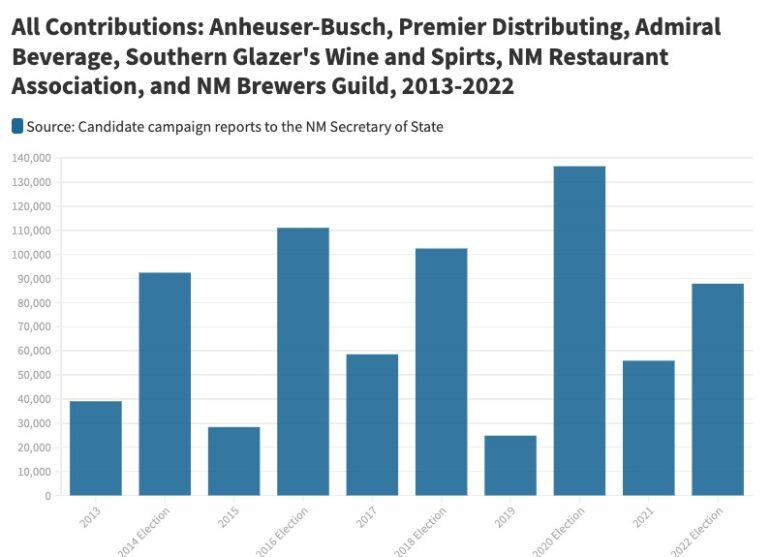

This year, as in the past, proponents of a tax increase were up against thousands of local businesses that sell alcohol and deep-pocketed corporations, like the world’s largest beer producer Anheuser Busch, which over the last decade has showered state lawmakers with hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But a couple factors had changed. First, more New Mexicans were dying from drinking than ever: from 2017 to 2021 alcohol attributable deaths statewide rose 47%, and now account for one in five deaths of working-age New Mexicans. And second, local media had covered the crisis in depth.

In October 2022, a group of concerned residents who supported the push began meeting weekly. The videoconferences occasionally swelled to over 100 people. Among the 20 core members was Shelley Mann Lev, a public health consultant who helped lead the campaign for a tax hike in 2017. It was “kitchen-table advocacy,” she said.

Rep. Joanne Ferrary, D-Las Cruces, who co-sponsored the unsuccessful legislation in 2017, would carry the new bill, as would Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, D-Albuquerque. They decided to introduce identical bills in the Senate and the House to increase the odds one would be folded into this year’s comprehensive tax package, which was widely expected to pass.

On December 12, 2022, Mann Lev and Sedillo Lopez met with Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham to seek her support. She had not previously shown much appetite for reining in alcohol: in 2021, she overruled her alcohol epidemiologist to sign a bill loosening alcohol regulations. According to Mann Lev, for a full hour Lujan Grisham grilled them about the science showing that alcohol taxes reduce harms.

As the meeting wound down, Sedillo Lopez asked the governor whether she was on board. According to Mann Lev, she said yes. “It was not defined what being ‘on board’ meant, but she did not oppose it.”

“A discussion worth having”

In the blur of the legislative session, scores of consequential proposals advance or disappear with little fanfare — but each hearing for the alcohol tax drew numerous supporters and opponents.

In the bill’s first hearing before the House Health & Human Services Committee, doctors and health experts told stories of people who’d died of alcohol-related causes and described studies showing that in states where alcohol taxes are raised, excessive drinking and its harms decline. In opposition to the bill, businesses that sell alcohol and their lobbyists offered familiar rebuttals: a rate hike would harm the economy while failing to address alcohol’s harms.

The bill passed its first committee, a distinction the 2017 effort never notched.

Ten days later, the House Taxation and Revenue Committee greeted the measure with more skepticism. Chairman Derrick Lente, D-Sandia Pueblo, who had great influence over whether it advanced, said his family had been “plagued by alcoholism” and imagined others in the room had similar stories. He did not outright say he opposed the tax hike but suggested it merited further deliberation. “Is it a discussion that is worth having? Absolutely.”

The committee tabled the bill, as is routine for tax measures, for possible inclusion in the final comprehensive tax package.

On February 28, the Senate Taxation and Revenue committee heard Sedillo Lopez’s companion bill. Chairman Benny Shendo, D-Jemez Pueblo, observed that alcohol contributes greatly to racial disparities — according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the life expectancy of Native American men is nearly eight years shorter than that of non-Hispanic white men — and he reflected on “close to 10” childhood friends he’d lost to drinking. But he seemed skeptical that the impact alcohol tax hikes had in other states would be replicated in tribal communities where alcohol consumption and possession are already prohibited.

Responding to prodding from Sedillo Lopez, he committed to considering the proposal for the tax package but nothing more. “I appreciate the debate and the discussion.”

A major miscalculation

Now the action moved behind closed doors. Ferrary met with a group of microbrewers and tried to win over House tax committee members, but the primary negotiation was with Lente. “The tax chair is the person who basically told me: This will fly. This won’t.” On his direction, she exempted local wineries and breweries from her tax proposal and removed a section indexing rates to inflation. Most significantly, she agreed to reduce the tax hike to 15¢-per-drink.

But when she and Sedillo Lopez and legislative staff met to revise the language, they introduced an error. By statute, beer is taxed per gallon and wine and liquor are taxed per liter, and the lawmakers mistakenly revised their bill to increase the tax 15¢ per those units, rather than by 15¢ per drink. Diluted over much larger volumes, the hike they wrote in was now barely more than a penny-per-drink. “We did not pick up that difference because we were in a hurry,” said Ferrary.

When the House tax committee circulated a draft of its omnibus bill on March 4, it included those watered down rates. “I was just shocked,” said Sedillo Lopez. “It was just wrong.” Having maintained a firm position through much of the session, the bill’s sponsors had suddenly given up nearly all their bargaining power.

Ferrary asked Lente to change the language but he said he had worked faithfully from what she had given him and revising it could delay the whole tax package. Ferrary also met with House Speaker Javier Martinez and urged him to push the Senate to amend the bill back to a 15¢-per-drink hike.

“I did commit to discussing with the Senate the possibility of them taking it up,” Martinez said in an interview.

The House passed the omnibus tax package with the watered-down tax rates on March 12. And at an unscheduled meeting three days later when the Senate tax committee revealed its amendments to the House tax bill, it included a 5¢-per-drink increase.

Just a fraction of the tax hike advocates had originally sought, it would still reduce statewide alcohol consumption by 1.8% and raise $50 million, estimated Boston University School of Public Health professor David Jernigan. When the advocates conferred the day after the Senate committee meeting, with two days left in the session, Mann Lev said the consensus was “while we strongly hoped for more significant action, the 5¢-per-drink increase in the Senate tax bill was a place to start.”

But the House wasn’t finished with the bill. Both chambers must agree on legislation and, in this case, the House rejected the raft of tax changes the Senate had made. So it fell to a committee of six lawmakers from both chambers, including the chairs of both tax committees, to hammer out the final version.

Lente had not publicly opposed the Senate’s 5¢ increase but at the negotiators’ first meeting the evening of March 16, he and the other House representatives sought to further reduce the rate. Rep. Micaela Cadena, D-Mesilla, criticized tobacco and alcohol taxes as ‘regressive’, even though evidence shows they disproportionately benefit the poor. And attributing the idea to Lente, Rep. Jason Harper, R-Rio Rancho, floated a 20% increase in tax rates for beer, wine and liquor.

Because New Mexico’s existing alcohol taxes are so low, a 20% hike would mean less than a penny-per-drink increase for beer and little more for wine and liquor.

Senate Majority Leader Peter Wirth, who was among the negotiators and had previously called for a tax increase sufficiently large to change drinkers’ behavior, offered no counterargument. He appeared not to recognize how small the proposal was — even lower than the original House tax proposal for wine and liquor — confessing later that “I didn’t really realize.” The increase was so small that at the present rate of inflation, it will be eroded nearly completely by the legislature’s next 60-day session.

Lente, Cadena, and Shendo joined with the two Republicans on the committee to approve the 20% hike. Wirth, disappointed, commended everyone for the conversation. “It’s a discussion we need to keep happening.”

Of the six lawmakers negotiating the alcohol component of the 2023 tax package, Sen. Peter Wirth was the only one not to raise a hand in favor of a 20% hike, which worked out to about a penny per drink. Video from the New Mexico Legislature website.

No representatives of the alcohol industry spoke at the meeting but their influence was unmistakable. In total, the six lawmakers on the conference committee have accepted more than $34,000 from alcohol businesses since 2013. Aside from former House Appropriations and Finance chairperson Patty Lundstrom, D-Gallup, Harper, who had taken $10,450, and Lente who had taken $8,700, had received more from the alcohol industry than any other sitting representative.

A first step

When the Senate cut her proposed tax hike to 5¢-per-drink, Ferrary was “devastated,” she texted at the time. But “for the House to come back and tear even that down, that is betrayal, ” she said.

Driving west after the session for vacation, she was already thinking about next year. “We’re not giving up,” she said. She planned to bring the proposed 25¢ tax to interim committees dealing with taxes and revenue, to educate other lawmakers, and to organize constituents to put more pressure on their elected officials — “to have more of a drumbeat.”

Sedillo Lopez was adamant, too. “It’s not over for me at all.” She spoke of alcohol as a generational challenge for New Mexicans, akin to climate change. “The education issues, the bad health outcomes, the adverse childhood experiences — I just think it’s the root cause of so many of our social ills.”

In a statement, Wirth said he was disappointed with the size of the enacted tax hike but saw it as a beginning. “We have taken an important step in the right direction and I am sure it will not be our last,” he wrote.

Martinez, who once chaired the House tax committee and has long sought to refocus tax policy to benefit working families, said all of this year’s tax reforms were “a work-in-progress,” including the hikes for alcohol. “For the first time in 30 years, that very inflexible liquor tax system finally began to bend — and we’re just getting started.”

Speaking by phone from his farm on Sandia Pueblo, Lente maintained that alcohol was an issue that “hits close to home,” but said he was careful not to allow his personal experience of alcohol to affect how he legislates for all New Mexicans. He acknowledged the final penny-a-drink hike seemed like “an insult” to those who pushed for more, but asked if he had any concerns about raising rates further after consideration in the interim, he said: “No, no, not at all,” adding, “I do things for the community and not to appease an industry.”

If legislators return to the topic, the terms of the debate will be different. The final legislation created an Alcohol Harms Alleviation fund and beginning in 2024, $25 million in annual alcohol tax revenues previously directed to the General Fund will be deposited there, eliminating a popular talking point among alcohol businesses who griped that lawmakers should do more with existing revenues before raising rates further.

Accounting for revenues from the penny-per-drink hike, the fund will receive an estimated $35 million annually — a negligible amount compared to the billions of dollars that alcohol costs the state in forgone productivity, unreimbursed healthcare, and property damage — but a substantial increase in resources for treatment and prevention.

Ferrary also tucked into a spending bill an appropriation for a new position in the Human Services Department to coordinate state agencies, treatment providers, and advocates around needed alcohol prevention programs.