Alcohol

Do alcohol taxes hurt poor people?

|

Illustration by Shelby Criswell

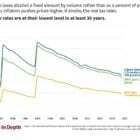

A bill that would raise state alcohol taxes for the first time in 30 years is in the hands of Democrats, who have a firm hold on both legislative chambers. But a major obstacle to passing the legislation is the concern voiced by some of their members about how an alcohol tax hike would affect low-income New Mexicans.

In an interim legislative meeting In October, Rep. Susan Herrera, a Democrat whose district in northern New Mexico has a higher share of residents in poverty than the state, said she refers to levies on alcohol and tobacco as ‘poor man’s taxes’ rather than as ‘sin taxes’.

“Not that I think poor people sin more than rich people,” she said, prompting laughter from her colleagues, “I just think they pay more for their sins.”

Paul Gessing, president of the local free market think tank The Rio Grande Foundation, testified to lawmakers that a tax on alcohol is regressive. Business interests and conservatives are making the argument, too. On Monday as the House Taxation and Revenue Committee discussed House Bill 230, which would raise state alcohol taxes to a quarter a drink, Sam DeWitt of the national Brewers Association tarred the proposal as “regressive.” So did Paul Gessing, president of the local free market think tank The Rio Grande Foundation, and Adam Hoffer of the Washington, D.C.-based Tax Foundation.

Sen. Antoinette Sedillo-Lopez, a Democrat representing the south side of Albuquerque who is sponsoring companion legislation, insisted the measure is meant to improve the health of lower-income New Mexicans, not to impoverish them. “This bill is about changing behavior.”

Alcohol taxes are regressive by definition, according to former state tax policy director Kelly O’Donnell, at least from a technical standpoint.