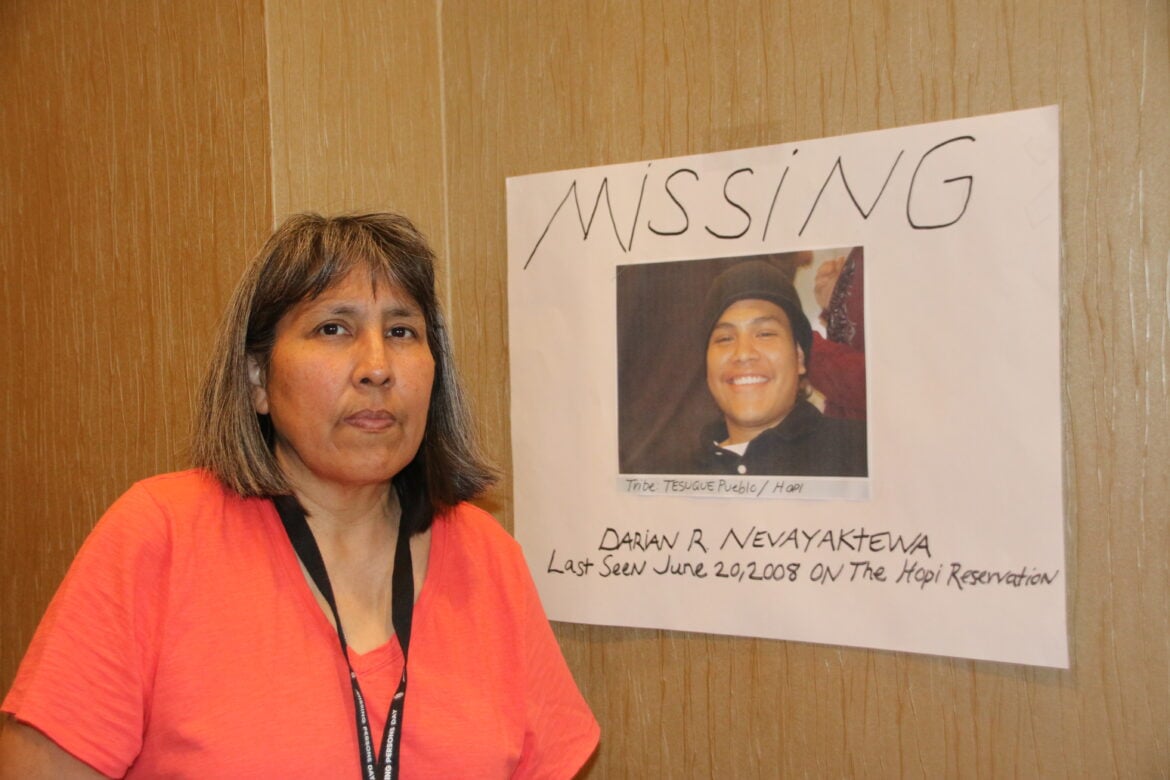

Darian Nevayaktewa went missing 15 years ago from northeastern Arizona. He was 19 and living in New Mexico with his mother, Lynette Pino. But it was during a summer visit to the Hopi reservation where his father lived that he disappeared after going to a gathering and never coming home.

Pino hasn’t stopped looking for answers about what happened to her son.

“We take it one day at a time and just pray that one of these days something will come out,” Pino said.

Her search brought her from Tesuque Pueblo to Albuquerque on Sunday for the second annual Missing in New Mexico Day. Nearly 200 Native Americans are missing from the state and the Navajo Nation, according to an FBI list last updated in November.

While geared toward people missing from New Mexico, Pino, who also attended last year, said the event provides face-to-face conversations with law enforcement and information about resources like search and rescue teams. After winter, she hopes to be able to organize another search for her son.

Over the past decade and a half, she’s struggled to get the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which still lists her son’s case as open on its website, to communicate with her.

From unanswered calls to dismissed concerns and victim blaming, dealing with law enforcement is one of the main obstacles in getting justice for missing or murdered relatives, Indigenous families say. Lawmakers in 2022 created Sunday’s event, which the state is required to host every year, in part to try to help solve that problem.

But Pino easily could have missed it.

Officials announced the date and location on Nov. 28, less than a week before the event, organized by the Indian Affairs Department and the Department of Public Safety. Dozens of chairs were empty when it kicked off with speeches from state officials in a hotel conference room.

Along with other affected families, Pino questioned whether the state did enough to raise awareness.

“Looking around here, there’s nobody,” Pino said, adding she learned about the event when a friend sent her a flyer. “It’s depressing. Maybe the advertising wasn’t good enough.”

Multiple state agencies posted about it on social media, and officials “reached out to tribal leadership to ensure comprehensive dissemination of information,” Indian Affairs spokesperson Aaron Lopez wrote to New Mexico In Depth on Monday.

The state doesn’t have an official attendance count because the event is open to the public and registration isn’t required, according to Herman Lovato, a spokesperson for the public safety department. Agency staff, Lovato said, interacted with about “30 individuals from families with missing persons.”

Josey Tenorio (Hopi), who has two siblings who were murdered, and a couple other advocates confronted Indian Affairs officials after their opening remarks, telling them she thinks they should’ve announced the date and location earlier.

“This room would’ve been filled with hundreds of families,” Tenorio told Indian Affairs Secretary-Designate James Mountain and Deputy Secretary Josett Monette.

Some families she’s in contact with didn’t know the event was happening, Tenorio said, and even if they had, the late notice would’ve made it difficult for people who live outside of Albuquerque to make it.

In response to the families’ criticisms, Monette said: “One perspective is that, of course, if we’re able to help a family – a family – that’s really good work. Of course we want to help as many families as we can.”

Monette said that in the future state officials want to “get the notice out as soon as possible” and are already looking at scheduling next year’s date.

During her talk with Mountain and Monette, Tenorio said affected families need to be included in a new Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons Advisory Council announced last week.

Tenorio is one of a couple dozen Indigenous families who traveled to Santa Fe in October to protest the disbanding of the state Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives Task Force earlier this year. A member of the task force proposed lawmakers create Missing in New Mexico Day after learning about similar events in other states.

Advocates and families, along with state leaders and law enforcement officials, will make up the advisory council, according to a news release. Pojoaque Pueblo Gov. Jenelle Roybal and Picuris Pueblo Gov. Craig Quanchello, who Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham appointed to lead the group, are selecting members.

“Their concerns are important and I believe we addressed them,” Mountain told New Mexico In Depth during Sunday’s event. “I was glad to be able to talk with them.”

Asked how officials addressed their concerns, Mountain said: “Hearing them out is really important, and that’s addressing that. I mean, what we have control of today is what we have control of today. Moving forward, though, I heard what they talked about and we exchanged contact information so that we can do a much better job on our end.”

Tenorio appeared skeptical that being listened to would lead to better results.

“They’re going to brush me off like they always do because they only tell us what we want to hear,” Tenorio said.